Designing Entrepreneurial Solutions to Address Urban/Inner City Problems

In the Community Development and Policy Studies (CDPS) Department’s field work throughout the Seventh District, CDPS contacts – in varying contexts – have voiced concerns about conditions impacting low- and

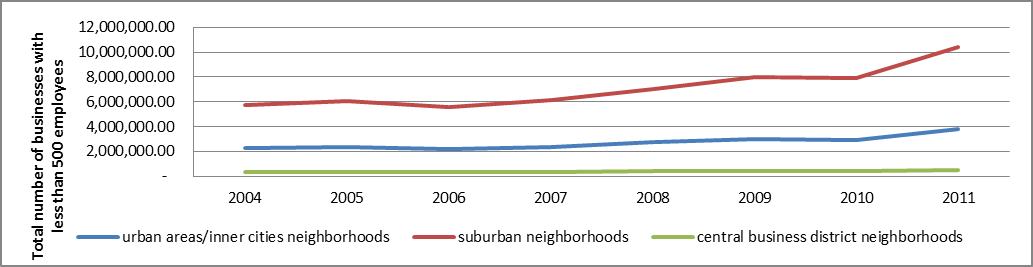

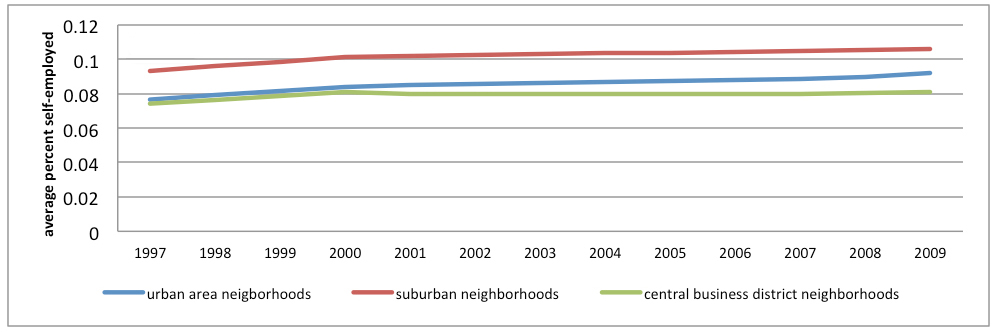

Encouraging business formation, increasing employment, and improving quality of life in inner cities are a few of the most important but most challenging goals for both policymakers and community development professionals serving economically marginalized urban areas. Urban/social entrepreneurs are taking on many of these challenges, designing market-based solutions to address urban problems in the transportation, education, housing, and safety spheres, among others. Self-employment and business creation (including sole proprietorships) have been on the rise in urban areas away from central business districts, including in some inner cities throughout the country, in many instances at rates comparable to surrounding suburbs. (See Figures 1 and 2 for trends in self-employment and small businesses in the U.S.). Employment clusters in the transportation, health, entertainment, education, medical, and technology sectors are making inner cities more competitive, and offering opportunities for business expansion particularly responsive to urban and inner city settings.1

1. Trends in small businesses across neighborhoods

2. Trend in self-employment/entrepreneurship

In October 2015, the Urban Entrepreneurship Initiative held its annual Urban Entrepreneurship Symposium in Detroit, co-hosted with the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, Wayne State University, and the New Economy Initiative, bringing together entrepreneurs, academics, community development experts and funders to discuss the challenges and opportunities in urban inner city areas, and showcase examples where entrepreneurs have turned business ideas into success, creating employment for inner city residents across skill levels.2 Most of the discussions centered on contextual problems in Detroit, although the issues are similar in many other U.S. cities.

The premise of the meeting was that urban entrepreneurship is distinct from entrepreneurship more generally, in that urban entrepreneurs often create their businesses with an awareness of a particular urban problem, consistent with the adage that the business owner can “do well while doing good.”3 This is an emerging way of thinking about entrepreneurship and the business opportunities in inner cities, and the discussions at the conference were designed to showcase this orientation. In this blog, we summarize some of the main lessons learned from the conference discussions, built around this new urban entrepreneurship paradigm.

Urban Problem Mining

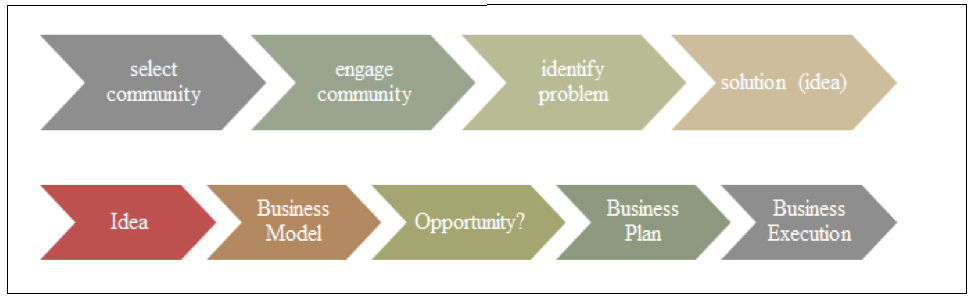

The new approach to entrepreneurship highlighted at the conference involves mining the intersection of technology, business development and community engagement to bring about greater opportunity within cities. In contrast to standard business training, which emphasizes business plans as the first step, this paradigm encourages entrepreneurs to consider “the problem space” in a given urban setting, and then how to tailor a business idea in a way that addresses it. This approach parallels approaches that have gained currency in engineering schools across the country, where the focus of learning has moved away from designing products and towards designing solutions.

3. Urban entrepreneurship model

Shocking the (Urban) World

The conference featured several urban businesses–large and small–that demonstrate this new type of thinking. For example, where many see a lack of quality education as a problem in urban areas, urban entrepreneurs have created small tutoring companies that use technology like Google Hangout to reach students throughout the country. At a larger scale, the transportation company Uber has responded to the absence of reliable, flexible transportation in many urban areas by deploying telecommunications and GPS technologies. Detroit’s Splitting Fares, another ride service, uses technology to facilitate communication and transportation. Metro EZ Ride, also in Detroit, partners with faith-based and workforce development organizations to rent unused vehicles for people who do not have access to transportation to jobs located outside of the city. According to the representative who spoke at the conference, they have hired 50 drivers to drive as many as 250 people per day to work in warmer months, and 800 per day during colder weather. Shotspotter uses technology to provide real time alerts to law enforcement in various cities as to where gunfire occurs, contributing to safer communities and improving the business environment of inner cities.

Obviously, cities still need more traditional businesses like restaurants and retail merchants. However, the urban entrepreneurship model provides tools for businesses to build upon a location’s comparative advantage(s), and address contextual disadvantages. This includes large businesses like Shinola, a manufacturer of watches, bicycles, and leather goods that provides entry-level jobs and skilled employment to more than 550 people in Detroit. As a representative of Shinola explained, the company chose Detroit with the understanding that they could build upon the manufacturing and steel production experience of workers.

Engaging the Community

It takes knowledge of a community to come up with business-based solutions to urban problems. As with any group of people, inhabitants of inner cities often distrust the idea of people from outside of their areas imposing solutions to local problems. As a presenter from the session on community engagement strategies put it, “anything for us, without us, is not about us.” That is why community engagement and even community organizing are integral to this model. Presenters at the conference spoke to the range of methods that have been used for soliciting community participation, including surveys, data analysis, interviews, focus groups and other methods. For example the Detroit Dialogues undertook a bike and walking tour initiative that went door to door collecting people’s personal accounts of what it means to them to be in their neighborhoods.4 Using a multiplicity of ways to engage with the community also reveals what works and what does not in terms of understanding a community and its concerns.

Accessing Capital and Funding

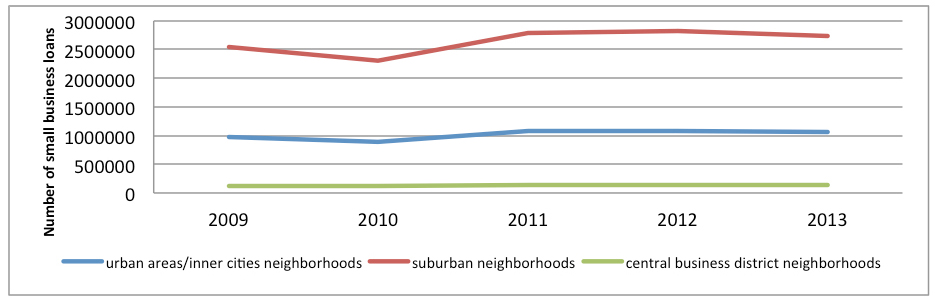

A model-based approach to addressing urban problems is not all that is needed to support business growth and formation and create jobs. Entrepreneurs and small business owners in many cities report difficulties in getting access to financing. Limited access to bank credit, equity capital, or even personal networks creates genuine barriers for many business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs (e.g., Figure 4 shows trends in CRA-reported small business bank loans). For the Urban Entrepreneurship Initiative, these financing challenges make an even stronger case for conceptualizing an urban business as one that responds to an urban problem.

4. Bank loans to small businesses

Conclusion

The Urban Entrepreneurship Initiative is pursuing the same fundamental goals as many other initiatives focusing on inner cities, that is, to support businesses that provide products and services for people in urban areas. Their contribution to the discussion is the recognition that the same techniques that architects and planners have used for generations to apply design solutions to buildings, roads, and public spaces, can now be applied to urban challenges like education, public safety, transportation, and others. Using this approach, the intent is to bring new technologies to old problems, and in doing so, inspire students, academics, business people, and funders to test new ways to improve the quality of life in urban areas. Moving forward, the goal is to integrate scalable strategies into the model, to bring about the kind of businesses that will create jobs and economic development a more significant way.

Footnotes

1 Newberger and Toussaint-Comeau, “Revitalizing Inner Cities: Connecting Research and Practice,” November 2015, Chicago Fed Letter No. 346. Available online.

2 Videos of the discussion are available online.

3 Osorio, A.E., and B. Ozkazanc-Pan, “Defining the ‘Urban’ in Urban Entrepreneurship: Implications for Economic Development Policy,” Academy of Management Proceeding, January 2014. Available online.

4 Clark, A., “How Storytelling heals and strengthens communities,” available online. Also see the New York Time Magazine, July 13, 2014, “Detroit Through Rose-Colored Glasses” for a collection of photos and stories of people in Detroit. Available online.