Redefining Rustbelt: Cross-City Perspectives on Connecting Health and Community Development

On March 16, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released its 2016 County Health Rankings1 showing a worsening of conditions in some “rustbelt” counties like Wayne County (Detroit), and Philadelphia County, ranking them lowest in their respective states in terms of the social and economic factors and physical environment that affect health. In order to improve economic and physical health in communities, especially in low-and-moderate income neighborhoods, the Federal Reserve Banks of Chicago-Detroit Branch, Cleveland and Philadelphia recently held a joint videoconference entitled “Connecting Health and Community Development” to share strategies for developing and investing in community assets. The conference’s focus on ‘healthy communities’ built upon broad efforts and initiatives undertaken by Federal Reserve community development units across the nation to convene public health and community development groups. These meetings have explored common objectives between the fields, the potential for community health needs assessments2 to address built infrastructure (strategies) in addition to health/healthcare disparities, and facilitate communication across existing public and private funding sources, including community development banks and community development financial institutions.3

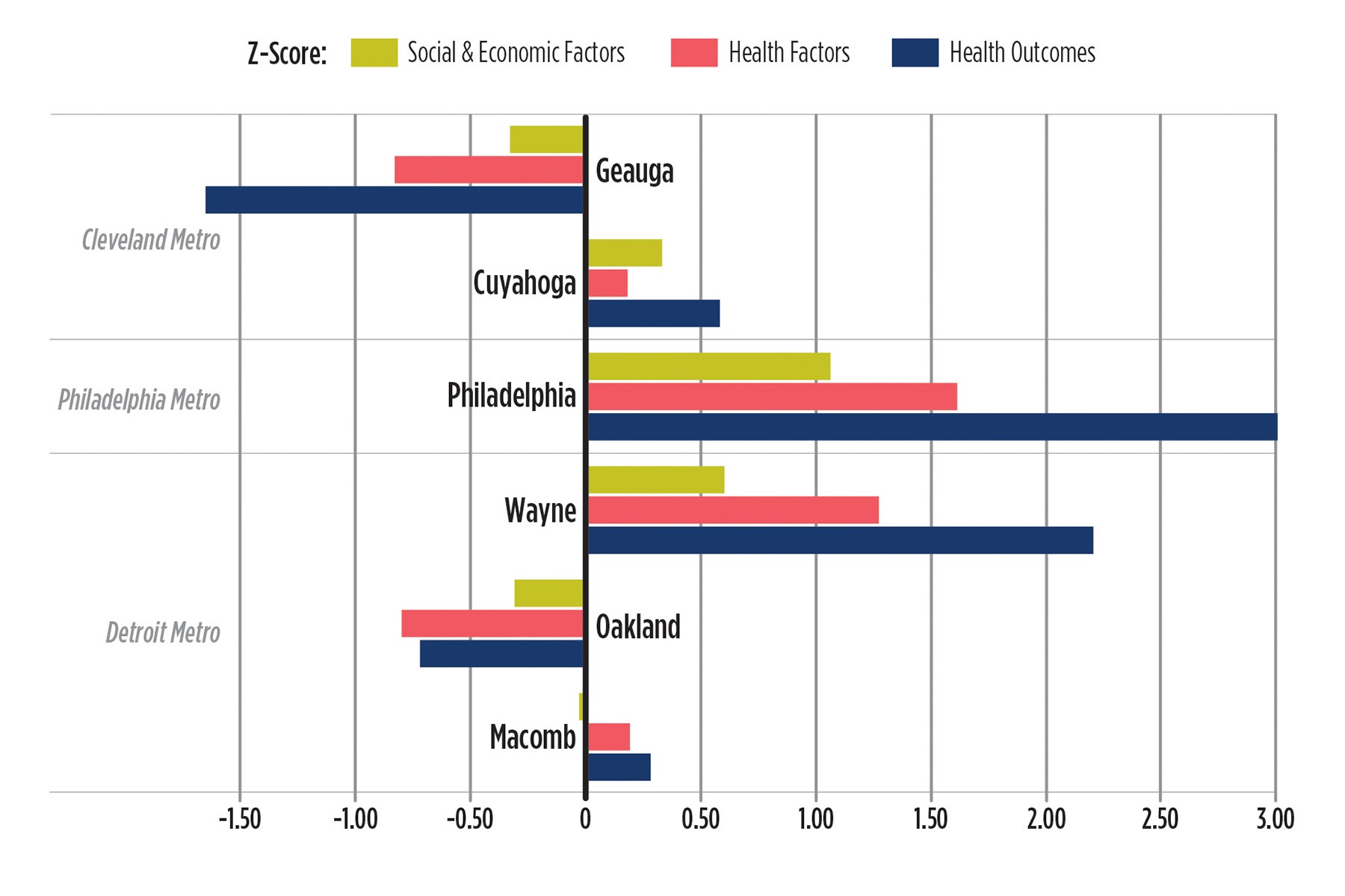

Chronically disinvested places in cities that line the nation’s ‘rustbelt’ such as Detroit, Cleveland and Philadelphia, lack many of the interconnected socioeconomic, physical, and environmental attributes that make for healthy communities, that is places with consistent investment in people and infrastructure. See Figure 1 for composite measure indicators of health factors, health outcomes, and socio-economic factors in the three cities. The health of residents in a neighborhood often has more to do with the community assets that shape their environment, such as access to recreation spaces, quality housing, and healthy foods, as it does with the presence of health care services. For decades, the public health field has documented correlations between negative health outcomes such as high incidence of asthma, obesity, and hospitalization, and socioeconomic factors such as low educational attainment, unemployment, and the physical and institutional make-up of neighborhoods.4

1. Health factors, health outcomes, and social & economic conditions — counties in Cleveland, Detroit and Philadelphia metros, 2016

Note: Health factors are measured based on weighted scores for health behaviors (i.e., smoking, obesity, food environment index, physical environment, etc…), clinical care (i.e., lack of insurance, physician care), social and economic factors (i.e., graduation rate, unemployment rate, income inequality etc…). Z-Score = (Measure in county - Average of state counties)/(Standard Deviation). Scores rank between -3 and 3. The more positive the score the worse the conditions underlying these factors relative to average measure for counties in the respective state.

Traditionally, the public health and community development sectors have been viewed as operating in separate spheres. However, given the socioeconomic determinants of health and the connection between health and economic outcomes, it has become clear that the potential for improving conditions in underinvested and less healthy communities can increase if both sectors work together. At the videoconference, coalitions of public health leaders, community organizations, philanthropies, and others discussed ways in which they develop projects and test programs to address the substandard conditions and amenities in neighborhoods to improve both socioeconomic and health outcomes. This article presents some highlights of the discussion that took place at the videoconference. (See Table 1 for an overview of community partnerships that were highlighted during the videoconference discussion).

Improving Access to Healthy Food

Public health and community development organizations have long recognized the high value of improving access to fresh fruits and vegetables and encouraging healthy eating. Interventions have focused on increasing the availability of food, as CDCs and CDFIs locate and finance grocery stores and farmers markets in urban neighborhoods. Eastern Market Corporation in Detroit, in partnership with Goodwill Industries, recently inaugurated its Red Truck Fresh Produce project, which creates a mini-produce store within a popular meat market staffed by veterans returning to the workforce. To drive demand, Michigan’s Double Up Food Bucks doubles the amount of food assistance for purchases of state-grown fruits and vegetables. Ohio’s fresh food financing fund combines state funding with financing from a national CDFI. Philadelphia’s Food Trust is piloting a USDA Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive (FINI) grant to allow patrons to get reimbursement when using EBT to buying produce at grocery stores as well as at farmers markets.

Addressing “Upstream” Health Risks through Data Analytics and Sharing

Partnerships in each of the cities have also emerged to address “upstream” determinants of health. The Health Improvement Partnership in Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) is a partner-led coalition that identified neighborhood-level social, economic, and environmental factors that contribute to community health, in order to develop a neighborhood health plan to address them. Likewise, the City of Cleveland public health and housing departments and Metro Health Hospital worked with a local community development corporation and others to address asthma and lead poisoning in city housing. By sharing data, the hospital and city housing department were able to identify families on both lists of asthma patients and households whose housing has been subject to code violations, in order to target interventions. In Detroit, with a similar goal of targeting interventions and using resources more efficiently, the Healthy Environments Partnership was formed in 2000 to identify factors linked with higher incidence of cardiovascular disease in the city including low physical activity, high stress, and poor access to healthy food. The goal of identifying and collecting data on these upstream factors is to develop community-responsive healthcare interventions and repair programs that keep people from living in unhealthy environments.

Funding Healthy Communities through New Partnerships

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), including the provision expanding Medicaid, provides a fresh opportunity to consider resources to promote community health and well-being. While federal money may be diminishing, non-profit hospitals and clinics are expanding their roles in transforming communities. The new ACA mandated Community Health Needs Assessments and Community Benefit Agreements compel these institutions to engage with their communities about disease prevention and general health improvement. Many are recognizing the importance of their economic impact toward these goals, and assuming more substantive roles in planning and financing built improvements and service delivery.

In addition, Medicaid expansion is shifting incentives around state health care spending. According to one participant in Cleveland, the expansion of Medicaid in Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania has motivated new strategies for addressing the social determinants of health. In Ohio, for example, the state is conditioning (withholding) one percent of its payments to managed care plans on realizing better health outcomes at lower costs. Another “pay-for-success” model in Detroit is based on the concept of “hot spotting.” Several nonprofits have entered into contracts with an area hospital to receive a flat payment for three months of intervention with high-hospital users (to help coordinate their care), with the opportunity to share in half of the cost savings if health expenditures decline over the following year. These examples illustrate steps that health systems are taking to shift money into community development-type activities – that is, away from treatment and towards upstream prevention.

Foundations and local governments are also vital to hospital/community partnerships. Philanthropies are supporting coalitions both as funders and as neutral conveners. In Cleveland, county and city agencies, including the Cuyahoga Board of Health and the Cleveland planning commission, have worked with foundations and local nonprofits to develop Cuyahoga Place Matters a health improvement plan taking a ‘health in all policies’ approach to land use, education, agriculture, housing, transportation, and urban development. Cities are also funding cross-departmental positions, as in Philadelphia where the planning and health departments are looking to integrate health impacts into plans for the whole city. In Detroit, the city council is developing incentives for businesses to invest in neighborhoods, approving zoning changes and sidewalk ordinances to encourage a built environment more conducive to health and well-being.

Some creative and nontraditional partnerships have formed as well. Neighborhood organizations in Cleveland have sponsored a series of community-based artist projects to provide an alternative channel for information focusing on exercise, healthy eating, and stemming domestic violence in order to reach overlooked audiences. Other unconventional participants include restaurant associations in Philadelphia working with the city to decrease the sodium content at restaurants that populate many poor neighborhoods; and CDFIs in Detroit which have created a fund to finance grassroots food businesses as a way to increase neighborhood investment and improve healthy food access.

Lessons Learned from Existing Partnerships and Takeaways from the Discussion

While cooperation between the community development and health sectors is in its early to intermediate stages, many cross-disciplinary, innovative, and inclusive coalitions operate in each of these cities, involving community developers, public health leaders, philanthropies, food-justice activists, and residential groups. The videoconference was an opportunity to share information and strategies, as the experiences described in each city resonated with participants in other cities, and there was talk in the different sites to explore possibilities of working together, including collaborating on planning grants and sharing tips for applying for federal monies.

Policymakers, economic and community development professionals, and more recently hospital administrators charged with community engagement, are better understanding the interrelationship and confluence of factors that impact community well-being and (ultimately) health. For example, a fresh food market is an important community asset, but planners must consider city transportation infrastructure to insure that people can get to it safely and on a convenient schedule, and co-location or proximity with complementary businesses and service providers, such as a pharmacy, daycare provider, bank/credit union, etc. In addition, initiatives have to be constructed to meet the reality of neighborhood and home environments, as residents may not have the time, the money, or the tools to prepare fresh foods. According to some participants, operating affordable neighborhood groceries is only getting more difficult with cutbacks in public funding.

Despite the many successful programs and collaborations highlighted, participants noted persistent challenges. For example, some community development practitioners remain unaware of the ACA requirements for hospitals to conduct community health assessments, or the incentives for insurance companies to fund preventative programs. In addition, joint work by the public health and community development communities does not always mesh with philanthropic agendas. In Cleveland, for example, the hospital foundations ended up not funding what appeared to be an arts rather than a community health program. Engaging the community is also a challenge. According to videoconference participants, some coalitions of community development and health practitioners do not yet reflect the voices of neighborhood residents they seek to serve. In some cities, neighborhoods have not effectively organized to deliver a clear message about what quality of life looks like for them. Governments respond to organized interests, but cross-disciplinary coalitions cannot problem-solve without properly engaging the people whom they are trying to impact.

Finally, advances in health data analytics help to clarify the impacts of poor socioeconomic conditions and improve the efficiency of health-focused interventions, but participants noted the limited scope and small scale of many of the interventions thus far. A better understanding of these programs is needed to make them scalable and to identify preventative interventions that yield meaningful cost savings. Scaling the types of programs and collaborations highlighted in the videoconference discussion also requires a longer timeline for documenting and measuring their impacts. The long-term savings realized from preventative care and sound, safe neighborhoods and infrastructure, should be evaluated against the high costs of socioeconomic exclusion and remedial health care down the road.

Table 1. Selected Resources for Healthy Communities

Program |

Location |

Activities |

Red Truck Fresh Produce |

Detroit |

Creates mini-produce store within meat market staffed by veterans |

Eastern Market |

Detroit |

Manages farmers markets and improves food access throughout Detroit |

Fresh Prescription |

Detroit |

Provides pregnant women, families with young children, or people with chronic disease coupons to purchase fresh food and vegetables at farmers markets. |

Healthy Environments Partnership |

Detroit |

Examines and develops interventions to address aspects of the social and physical environment that contribute to racial and socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular disease |

Double Up Food Bucks |

Michigan |

Doubles the funds available on SNAP Bridge Card when purchasing fresh fruits and vegetables grown in Michigan |

Michigan Good Food Fund |

Michigan |

Finances healthy food production, distribution, processing, and retail projects that benefit underserved communities throughout Michigan |

Michigan Power to Thrive |

Michigan |

Organizes a network of organizations in health, housing, education, transportation and other sectors to adopt a "health in all policies" approach |

Fresh Food Financing Fund |

Ohio |

Supports the development of new and existing grocery stores and other healthy food retail in underserved areas throughout Ohio |

Health Improvement Partnership |

Cuyahoga County |

Creates project to share data between the hospital and the housing departments |

Place Matters |

Cuyahoga County |

Engages policy makers and community members to develop policies that create conditions for optimal health and reduce inequities |

Redlining and Health Equity |

Cleveland |

Examines history of race, redlining and their relationship to health equity |

HEAL Report |

Cleveland |

Tests the feasibility of a community-led approach for healthy eating and active living |

The Arts and Healthy Living |

Cleveland |

Funds creative projects to spur new conversations about community health and preventative care |

Edwin's Restaurant |

Cleveland |

Works towards reducing community stresses related to post-incarceration |

Food Trust Healthy Corner Store Initiative |

Philadelphia |

Increases the availability and awareness of healthy foods in corner stores in Philadelphia. |

Philly Food Bucks |

Philadelphia |

Supports projects to increase the purchase of fruits and vegetables among low-income consumers participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) |

Delaware Valley Health Communities Task Force |

Philadelphia |

Brings together public health, planning, and related professionals to integrate planning and public health sectors |

Health, Recreation and Literacy Center |

Philadelphia |

Provides healthcare, literacy and recreational services under one roof for children and families in South Philadelphia |

Footnotes

2 CDC description of CHNAs available online.

4 See, “Socio, Economic and Environmental Determinants of Health”, Chapter 4. Durham County Community Health Assessment, available online. Also see this report.