Revisiting the Promise and Problems of Inner City Economic Development: The Role of Industry Clusters

Last fall, Detroit provided an illustrative backdrop for a summit on economic advancement in distressed communities, sponsored by the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, the Upjohn Institute, Sage Publications and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. The May 2016 Special Issue of Economic Development Quarterly makes available both the new research presented at the event, as well as a discussion paper highlighting research findings and practitioner perspectives on revitalizing inner cities.

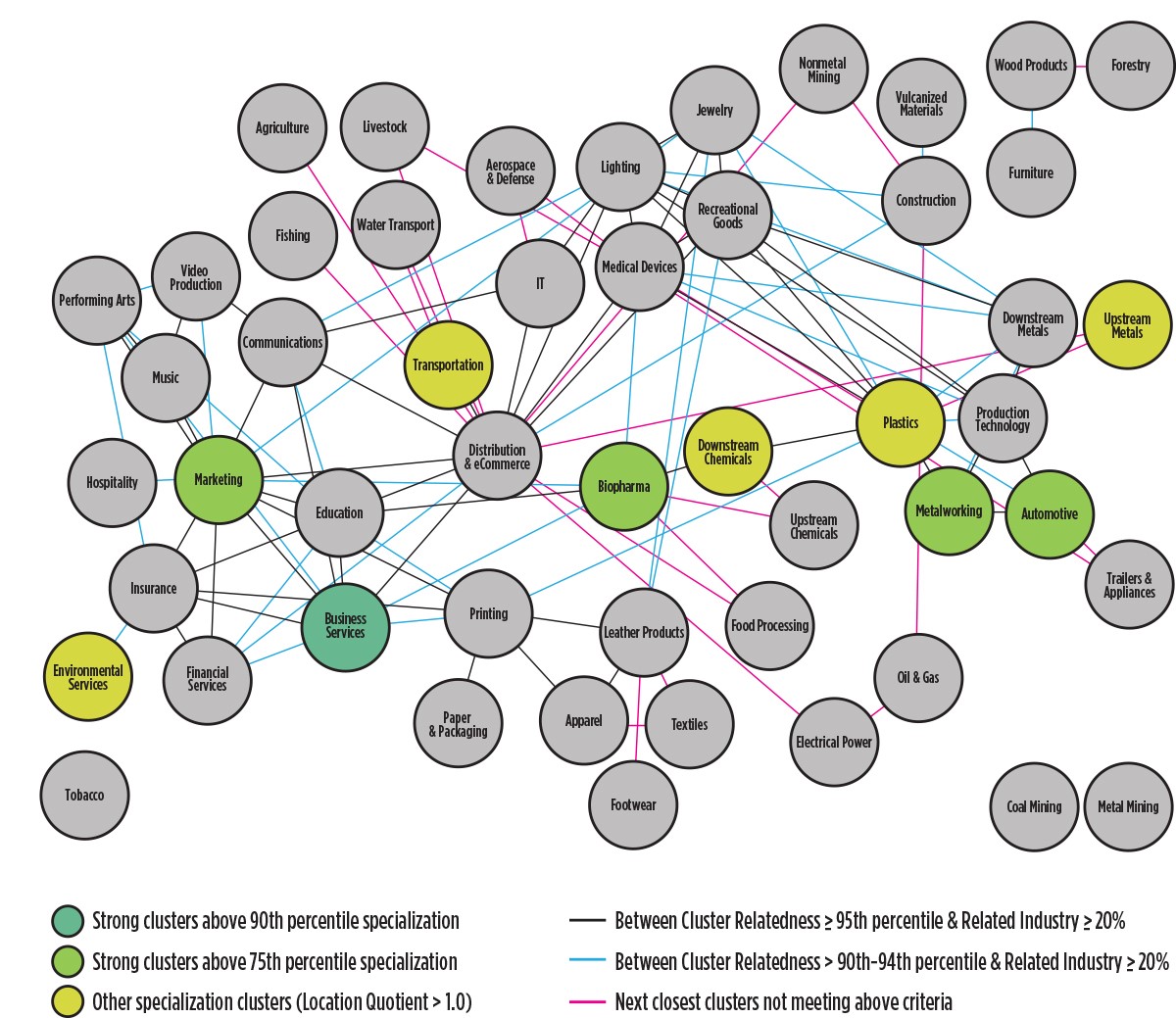

One of the main topics of discussion at the summit was the effectiveness of cluster-based development strategies in inner cities.1 Clusters are geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field including (1) linked industries and other entities, such as suppliers of specialized inputs and specialized infrastructure; (2) distribution channels and customers, manufacturers of complementary products, and companies related by skill sets, technologies, or common inputs; and (3) related institutions such as research organizations, universities, standard-setting organizations, training entities, and others (Porter, 1998). (See Figure 1 for an illustration of the industry clusters in the Detroit Metropolitan Area and their linkages).

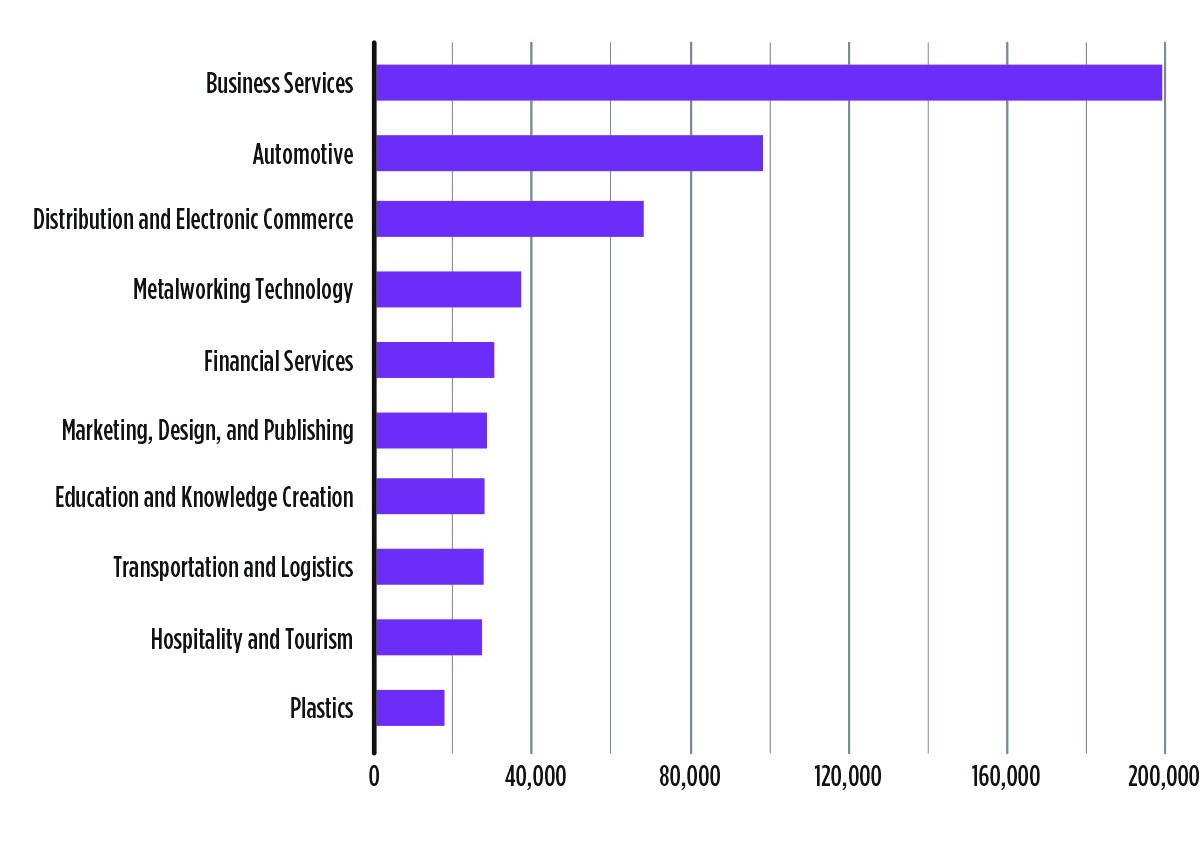

Over the past few decades, research by Michael Porter and others has shown that large traded industry clusters spur innovation and enhance productivity; and are prevalent in locations that achieve better economic performance. (Traded industries are industries that are concentrated in a subset of geographic areas and sell to other regions and nations. Local clusters provide services or products mostly for the local market)2 In the Detroit Metropolitan area, traded clusters accounted for more than 600,000 jobs as of 2013, according to the U.S. Cluster Mapping Project. Although the economic situation in the city of Detroit remains challenging, the automotive sector, despite its unusual recent history, illustrates the cluster concept (it is second in terms of number employed in the MSA only to ‘business services’). Automotive and auto supplier firms working in proximity benefit from both information networks and a local pool of engineers, designers, and workers. Other important traded clusters in the Detroit area include metalworking, marketing and design, and metal manufacturing (See Figure 2).

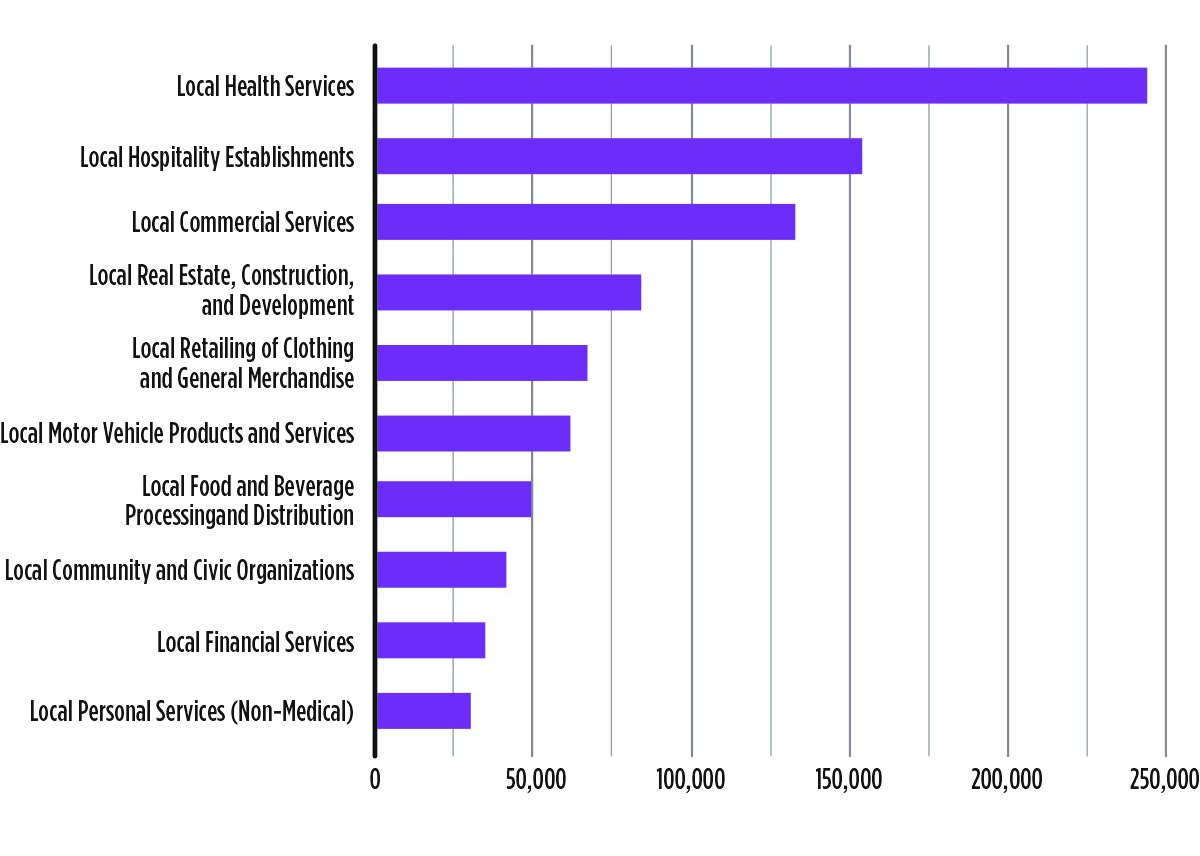

Local clusters in the Detroit MSA generate even more employment and accounted for more than 1 million jobs as of 2013 (Figure 3).

1. Cluster linkages and economic diversification — Detroit, MI metropolitan area, 2013

2. Top ten employment by traded cluster in Detroit MSA, 2013

3. Top ten employment by local cluster in Detroit MSA, 2013

Public Policy Support for Clusters

Cluster strategies have gained traction in recent decades to the point of becoming a part of the basic toolkit for local economic development authorities throughout the country. Cluster-based economic development policies involve identifying (e.g., through cluster analysis) an area’s sector strengths in order to be purposeful about the way resources are directed to expand economic opportunities. A good cluster-based development strategy involves creating an environment that bolsters cluster dynamics, which includes: encouraging related businesses to locate in ways that foster knowledge transfers; supporting science and technology infrastructure; fostering policies that improve education and workforce training; building specialized infrastructure; and promoting exports.

Additional Strategies for Practitioners to Support Clusters

Many of the practitioners who attended the summit support the thinking that industry and regional clusters are effective tools for the development of regions. But they also expressed concern as to whether cluster strategies can lead to strong economic development and growth for inner cities without more targeted support. Lower levels of educational attainment often impede inner-city residents from competing in emerging high-skill and high-wage sectors in many industry clusters. Institutional or historical obstacles also play a part in whether economic development benefits inner-city residents. For example, limited access to information resources and (commercial and financial) networks among black and Latino business owners often discourages participation in the financial system, which, in turn impedes business creation and development.

Realizing more fully the benefits of cluster industries in urban areas like Detroit requires economic development, training, and business development practitioners (and funders) to make some targeted refinements. Businesses that are pervasive in urban areas and that create jobs over a wide range of skills for inner-city residents could be singled out to receive greater investment. Additional investments could be directed at workforce training that connects trainees to businesses in inner cities and regional clusters. It may also be important to designate funding to organizations that not only upgrade the skills of workers, but can also provide greater case management for the social and personal challenges that many trainees face.

In addition, investments are needed to ensure that minority business owners are better connected to services that support local entrepreneurs. Training programs may need to focus on procurement and supply chains that connect minority business owners to both local and regional clusters. Programs may also be needed that construct resource networks for minority business owners, including accountants, attorneys and other professionals. With respect to credit access, trainers may need to focus on financial literacy and recordkeeping to improve the capital-readiness of small businesses, and identify best-practices among financial institutions that encourage minority businesses to seek bank financing. Local regulations or other mechanisms may also be needed to ensure that resources reach traditionally disadvantaged groups.

If industry cluster-based development policies are to represent a promising means of revitalizing inner cities, these strategies must address a range of issues and barriers facing residents. A fuller set of interventions related to developing human capital, business owner preparedness, credit access, and other issues may be needed for inner cities to realize the benefits of clusters and regional growth.

Summary of Recommendations

We summarize the main takeaways from the summit for optimizing the employment prospects of clusters to revitalize inner cities in ways that are also inclusive of inner city residents, business owners, and workers.

Investing in cluster development in urban areas

- Map the cluster composition of a region and identify which of these regional clusters also have representation in the city.

- Develop business accelerator programs that connect businesses in the inner city to the rest of the region.

- Coordinate cluster-building strategies between city and suburban communities.

- Support businesses that are pervasive in urban areas and that can create jobs over a wide range of skills for inner city residents.

Expanding training for workers

- Identify the human capital and employment skills that are needed by businesses and organizations in both inner-city and regional clusters.

- Identify or designate new sources of funding for integrating minority workers.

- Engage employers as training programs are developed, asking them for input on market trends and curriculum development.

- Create programs that develop social networks and other connections between people in higher poverty areas and cluster-related employment opportunities.

- Modify the terms stipulated by funding and reimbursement sources in order to (1) help cover the costs of skills remediation; (2) recognize that completion of remediation training is a successful outcome; and (3) include interventions that address the emotional and physical health of workers as part of job readiness training.

Supporting small and minority business owners

- Connect entrepreneurial ecosystems to small and minority business owners.

- Encourage small business training programs to use economic development tools (not just community development tools) to link small businesses to clusters, including training on procurement, supply chains, small manufacturing and logistics solutions.

- Offer financial literacy and training in recordkeeping to improve the capital-readiness of small business owners.

- Identify best practices within financial institutions that hire minority loan officers to focus on opportunities and encourage business owners to seek bank financing.

- Support minority business owners who receive funding (loans, grants, etc.) with resource networks that include accountants, attorneys, and other professionals.

Footnotes

1 In the United States, the term "inner city" often signifies lower-income residential districts in the city center and nearby areas, with the additional connotation of impoverished black and/or Hispanic neighborhoods. The Institute for Competitive Inner City (ICIC) offers a definition based on economic distress level, which has been adopted by many researchers. According to ICIC, inner cities are contiguous census tracts in central cities that have a poverty rate of 20 percent or higher, or have two of three other criteria: poverty rate of 1.5 times (or more) than the MSA; median household income of 50 percent or less of the MSA median; and unemployment rate is 1.5 times or more than the MSA rate