The fiscal state of the states (and municipalities): Not so good

Plenty of evidence is emerging that state and local governments are headed into a major fiscal pinch. Tax revenues are decreasing across the board, as everything from corporate profits to employment declines. The big question is how well are the states positioned to weather this storm? Is there anything different in the nature of this economic slowdown that will make circumstances more difficult?

Based on some preliminary evidence, the future looks challenging. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities released a survey of state budget conditions on February 25, 2008. The survey reported 25 states having budget deficits for fiscal year 2009. Specific estimates of the magnitude of the deficits were available for 21 states. These particular states report an aggregate gap of between $36 billion and $38 billion, representing roughly 8% to 9% of total general fund spending. Of the states in the Seventh Federal Reserve District reporting a gap, Illinois has a $1.8 billion deficit (6.6% of general fund); Iowa, $350 million (6%); and Wisconsin, $652 million (4.8%).

The center’s report notes that one of the more vexing fiscal problems is the current instability of property tax revenues related to the housing downturn and mortgage foreclosures. In the 2001 recession, states were able to push expenditures on to local governments because property tax revenues were relatively stable. In the current housing crisis, it is more likely that local governments will be asking state governments for help.

The report also finds that states are rapidly drawing down rainy day funds. These fund levels peaked at 11.5% of annual state spending in fiscal year 2006 and are estimated to decline to 6.7% of state spending by the end of this fiscal year. It is unlikely that this is sufficient to see the states through even a shallow recession.

A final national development is that at the February meeting of the National Governors Association, the governors requested that the federal government offer a fiscal stimulus package for the states aimed at financing infrastructure investments. It is unlikely that this will go anywhere. In the 2001 recession, the federal government offered a $20 billion aid package to the states. Half of the $20 billion was earmarked for a temporary increase in the share of federal support for Medicaid programs, with the remaining half set aside for general grants based on population.

A closer look at the impact of the housing downturn on state and local revenues

The fallout from the subprime loans and foreclosures has had a negative effect on state and local revenues. The United States Conference of Mayors (and the Council for the New American City) hired the consulting firm Global Insight to estimate the implications of the mortgage crisis. The firm estimates that U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) will be $166 billion lower than otherwise because of the crisis and that 524,000 fewer jobs will be created. The firm further estimates a $1.2 trillion decline in property values in 2008.

The report provides estimates of metropolitan growth rates and changes in tax revenues for selected metros and states. For example, the estimated real gross metropolitan product (GMP) growth rate for metro Chicago in 2008 will be 2.23%. This represents a 0.56% reduction, or $3.9 billion decrease, attributable to the mortgage crisis. Metro Detroit’s real GMP growth rate is estimated at 1.3%. A reduction of 0.97% is attributable to the housing slowdown representing a $3.2 billion decline in GMP.

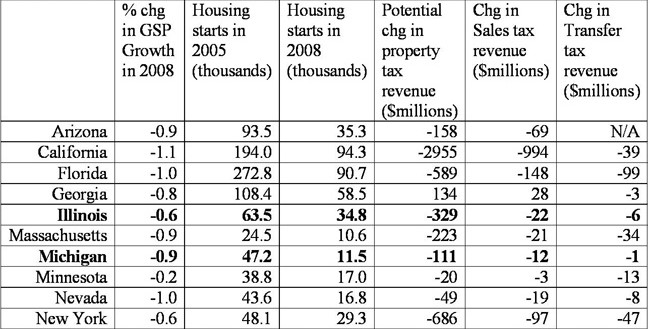

As for changes in tax revenues, the following table provides the fiscal impact estimates for ten states.

1. Estimated fiscal impact of housing slowdown

As the table illustrates the fallout goes beyond just property tax revenues. Sales taxes decline because of the reduction in big-ticket items, such as appliances and furniture, that occur during a housing slump. Transfer taxes—the taxes on the passing of a title to property from one person (or entity) to another—fall in response to the lower volume of transactions; in recent years, transfer taxes had become increasingly important to municipalities. All in all, such trends suggest significant challenges.

What is the fiscal state of the states? Not very good. And it appears that the housing slowdown will make conditions more challenging than was found during the 2000-01 downturn.