The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

The Midwest has been undergoing a costly but necessary process of rebuilding its economy. This ordeal of change has dramatically altered state development policies in recent years.

Economic change in the 1980s has been something of a puzzle in the Midwest. The decade began with two short but severe recessions, which raised fears of a collapse of the region’s economy. But a strong economic expansion by mid-decade prompted some commentators to predict an economic renaissance for the Midwest comparable to the New England experience a decade earlier. Clearly, both images of the Midwest were distorted by a failure to isolate long-term economic forces—the kind economists call “structural changes”—from short-term economic forces, such as the business cycle.

State policymakers have been caught in the middle of these economic forces, trying to develop long-run strategies at a time when short-run resources have been dwindling. Policymakers have begun to take a fresh look at their states’ economies and to design new, more flexible policies that meet the needs of the 1980s. The new approaches are a direct result of a better understanding of how their states’ economies are changing.

The changing economic environment

The economy of the region (defined here as Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin) received more than its share of battering by the ups and downs of the business cycle. Structural changes amplified those downs and dampened the ups. Among the most important of these forces were rising international competition, the energy dislocations of the 1970s, and a general shift in the nation’s economic center of gravity toward the South and West. Making matters worse, an unsustainable boom in agriculture went bust.

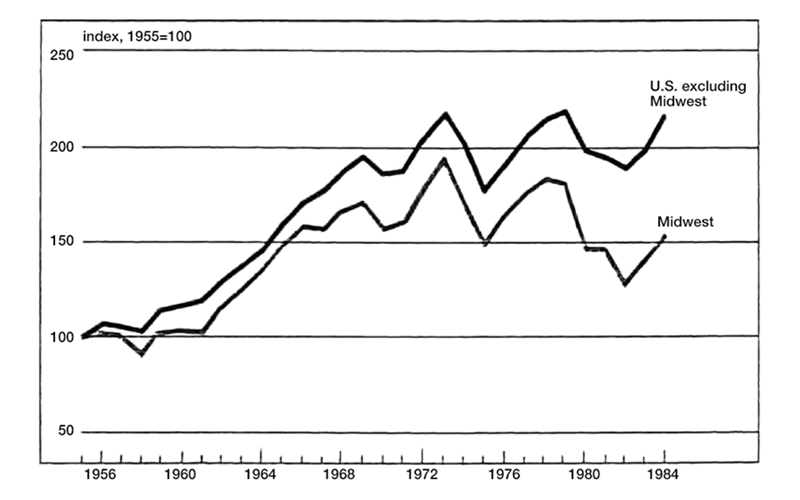

The effects of these structural forces were often masked in the beginning by the short-term business cycle. But the results of structural change were cumulative. Businesses failed or cut back; whole industries stagnated or declined; unemployment remained stubbornly high, and some people “voted with their feet,” emigrating South and West to warmth and work. The figures eventually told the story: Midwest manufacturing output began a declining trend after 1970. Manufacturing output in the rest of the nation was relatively stable. Thus, the Midwest has been “deindustrializing,” not only in the sense that its output shrank relative to the rest of the country, but that its output declined in absolute terms. Now, in 1987, the Midwest has found that the U.S. economy is much less dependent on its industrial heartland than it had been for most of the twentieth century.

This decline in manufacturing output was not accompanied by a shift from manufacturing to service output. In the Midwest, manufacturing’s share of the economy has remained fairly stable over the years, as it has at the national level. The Midwest’s nonmanufacturing output, including services, however, has lagged the national growth rate, even declining 10 percent between 1978 and 1982. As a result, the decline in manufacturing output has not meant that the Midwest is any less dependent on its manufacturing sector.

1. Manufacturing output trends

The general effect was not merely economically depressing, it was psychologically depressing. In gloomily assessing the Midwest, business analysts rounded up the usual suspects—aging manufacturing plants, high wages and taxes, climate, stodgy management—and characterized the region as old, cold, and rusting.

What was sometimes forgotten is the economic adage: “the market works.” Economic forces in the long run tend to move regional growth rates toward the national average—that is, regional growth rates tend to converge rather than diverge. While the Midwest’s economy has undergone often wrenching changes, these changes ultimately strengthen the region’s economy by forcing businesses to be more efficient in order to meet competition from outside the region. Without a clear understanding of these economic forces, state policymakers cannot be effective.

2. Manufacturing output trends by state

New approaches to state policies

Deindustrialization forced state governments to reshape their approaches to development. Smokestack chasing—ad hoc programs to attract specific manufacturing plants to a region—proved not terribly useful. Studies on the location decisions of companies cast doubt on the long-run effectiveness of state efforts to attract businesses by offering them tax and financing incentives. Such plans also had the side effect of irritating the existing business community, which frequently argued that the newcomers were being provided benefits at the expense of established businesses.

There are, of course, limits to what a state can do to improve its own economy. Most of the structural forces affecting states are national or international in scope. Accordingly, states have traditionally attempted to ease the burden of structural change with unemployment benefits, retraining programs, and a wide range of social services. But these are relatively passive responses.

There is a growing belief among state policymakers that economic development strategies can slow and even reverse economic decline. If this is true—and the jury is still out—it can only be true when public and private decision-makers have a clear view of the strengths and weaknesses of their state’s economy and a solid understanding of the structural changes affecting their state.

Since 1984, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin have each produced new development plans, designed to address the structural changes in their economies.1 Unlike their “quick-fix” predecessors, these plans are more strongly founded on data collection and analysis and stress long-term strategies. While each plan reflects the unique features of its state, three common themes emerge from them:

- A need to revitalize each state’s manufacturing sector,

- A stress on technology transfer to provide the spark for renewed growth, and

- The nurturing of an economic climate in which firms can thrive.

The interest in manufacturing seems appropriate, since the District historically has had its highest degree of economic specialization in, and has derived its highest contribution to, value added from its manufacturing sector. Moreover, the association between declining manufacturing output and weakness in nonmanufacturing and services suggests that attention focused on manufacturing will also benefit nonmanufacturing. For example, Michigan has targeted the automotive industry in an effort to assist in improving the worldwide competitiveness of the state’s most important industry.

One of the most effective ways to revitalize any economy is through technological advancement, the second common theme of the states’ plans. Stressing both the implementation of existing technology, such as robotics and computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM), and the search for new technology, policymakers hope to assist industries in lowering labor costs, improving productivity, and thus boosting competitiveness. For example, both Michigan and Illinois are currently striving to attract a multi¬billion dollar subatomic research facility to their state. Indiana intends to set up technology transfer centers to facilitate the transfer of new technology to existing firms.

Finally, the attention to economic climate, the third common theme, is designed to create an atmosphere that is conducive to growth. The focus on a state’s economic “climate” goes far beyond appeasing businesspeople with low taxes and tax abatement, which have widely been challenged as effective tools for economic development. Policymakers are becoming increasingly aware that the quality of services they provide affects their state’s competitiveness. Like any other input into the production process, poor quality in roads, water, and other types of state-provided services can raise production costs and reduce competitiveness. Moreover, poor quality of public services inhibits the creation of new firms and the attraction of out-of-state firms, just as easily as it harms existing firms.

In improving the region’s economic climate, all types of firms—large and small, new and old—benefit, thus creating a balanced approach to quality and cost of services for both existing and new firms. For example, Illinois’ program allocates public funds to infrastructure improvements and small business loans while trying to keep taxes in line with neighboring states.

Iowa’s plan, Rebuilding Iowa’s Economy, exemplifies how these common themes relate to the state’s unique economy. Iowa’s high degree of economic specialization in agriculture-related industries served it well until the “farm crisis” of the 1980s. Yet, when the need arose for increased state development activity in the late 1970s, Iowa focused on its existing strengths in agriculture by searching for ways to broaden its narrow dependence on two crops—corn and soybeans. One of its approaches, which relates to the theme of economic climate, has been to search for entrepreneurial gaps that can broaden its agricultural base. In addition, it stressed the importance of technology through its support of technology-oriented agronomy and biotechnology.

Encouraging signs for the future

Although smokestack chasing has not totally lost its appeal, state development programs have vastly improved in the 1980s. In contrast to state policies that once lacked coordination and a clear economic underpinning, current development strategies are more comprehensive in scope. Increasing emphasis is being placed on the long-run costs and benefits of programs, priorities established among competing programs, and coordination of programs and institutions to achieve the desired results.

Are the state plans working? It is too early to say, and their impact may never be clearly known. But they are pointed in the right direction. They recognize, as did the economist Joseph Schumpeter, that capitalism is “by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary.” Notably, the plans do not resist the structural change taking place in the Midwest’s economy. They accept it and try to adapt the advantages the Midwest already has to the change it is undergoing.

In the summer of 1987, there are a few hopeful signs. The Conference Board says that “help-wanted” linage in Midwestern newspapers is well above that in other areas of the country. The agricultural decline shows signs of bottoming out, although the national policies and international market structures that led to the decline are still operating. In manufacturing, the auto industry continues to post profits, despite a marked slowdown in sales from several years ago.

These are modest signs, to be sure, but may reflect a favorable restructuring of the Midwest’s underlying economy. To test for permanent improvements in the region’s economy, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago performed a simple experiment. With the aid of a recent Wharton Econometrics forecast of industrial production growth by industry between 1986 and 1996, we calculated what industrial production growth would be for the Midwest, using first its current industrial structure and second its industrial structure in 1972. The result was that the current structure would provide a slightly higher growth rate than the 1972 structure. Although many other factors will determine the actual growth performance of Midwest manufacturing over the next ten years, the experiment indicates the region’s current structure is more conducive to growth than in the past.

Economic change is a collection of gradual processes. Short-run gains could be obliterated by some national or international event beyond the control of state policymakers. But the combination of market forces and intelligent state policymaking in recent years prompts cautious hope. Winston Churchill, speaking on another matter, said, “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” We may be seeing the end of the beginning of the Midwest’s revitalization. At such a time it is important to remember that, while the way down was painful, the way back up will be hard work.

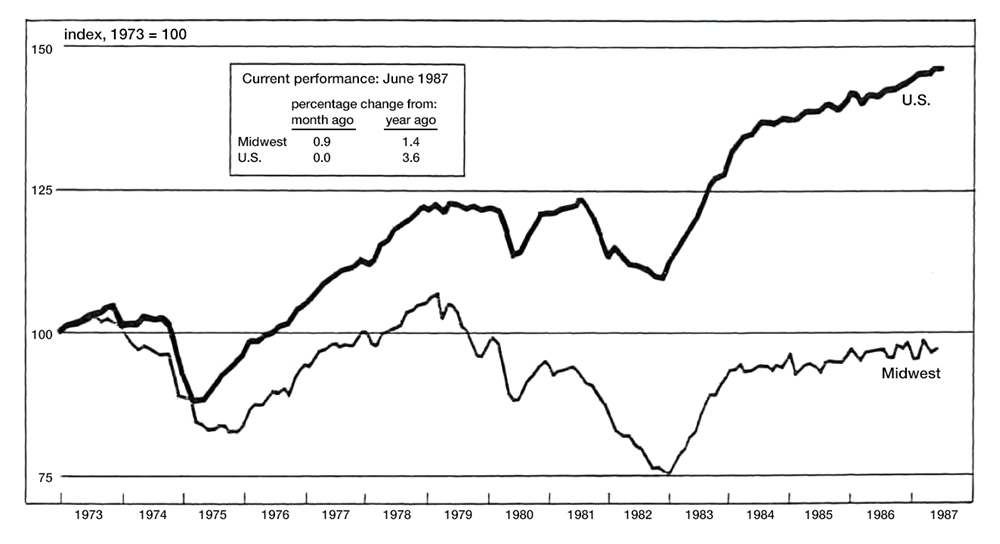

MMI—Midwest Manufacturing Index

Manufacturing activity in the Midwest (defined here as comprising Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin) rose 0.9 percent in June, following two months of decline from its peak in the current expansion. In contrast, activity nationally was virtually flat, after rising steadily throughout the year.

Manufacturing activity in the Midwest experienced a marked slowdown in 1984 similar to the national slowdown. Since then, the pace in the Midwest has lagged the nation. For example, the current level in the Midwest is only 1.4 percent above its year-ago mark, or less than half the national gain of 3.6 percent.

Note

1 The plans are: Illinois, Building Illinois: A Five Year Strategic Plan for the Development of the Illinois Economy (1985); Indiana, In Step With the Future… Indiana’s Strategic Economic Development Plan (1984); Iowa, Rebuilding Iowa’s Economy: A Comprehensive State Economic Development Plan (1985); Michigan, The Path to Prosperity (1984); and Wisconsin, The Final Report of the Wisconsin Strategic Development Commission (1985).