The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Following a period of strong growth in the 1960s, the Midwest began a protracted period of decline in the 1970s. By the early 1980s, the terms “Rust Belt” and “Midwest economy” had become synonymous. However, based on its performance since the mid-1980s, and especially during the 1990s, the Midwest is now better symbolized as the “Heart of America.”1 Since 1990, the economic growth of this industrial heartland has been leading the nation in many sectors.

While many other U.S. regions have experienced significant growth over the past 15 years, this has usually been followed by a notable economic slowdown. This has been observed in the oil economy of the Southwest in the early 1980s, the New England miracle of the mid-1980s, and in California, following the reduction of military spending in the 1990s.

The relative economic strength of the Midwest was in many ways most visible in 1995—although an economic slowdown early in the year was concentrated in the Midwest, the region posted stronger growth than the nation in many sectors.

The early 1995 slump was caused by an excess inventory correction, which slowed production. Except in the construction and steel industries, the Midwest performed as well as, or somewhat better than, the nation for the year. This Chicago Fed Letter reviews the regional performance of the Midwest economy during 1995 and the extent to which that performance reflects the region's renewed economic strength.2

Labor market

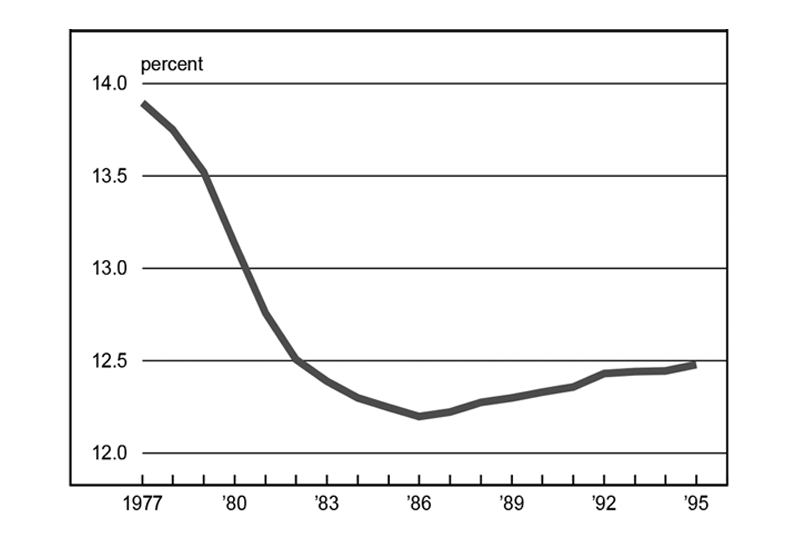

The Midwest's economic strength is reflected in its growth in employment. Since 1988, Midwest employment growth has exceeded that of the nation by 0.3% per year. In 1995, total employment increased by 2.6% in the Midwest, compared to only 2.3% in the nation. Since 1986, the Midwest's share of total employment has been edging up. After falling from almost 14% of total employment in 1977 to 12.2% in 1986, the Midwest share moved up to 12.5% in 1995 (see figure 1). Employment growth in 1995 for Chicago and Detroit was about the same as regional growth, while Milwaukee's employment growth lagged behind at 1.8%.

1. Midwest share of U.S. total employment

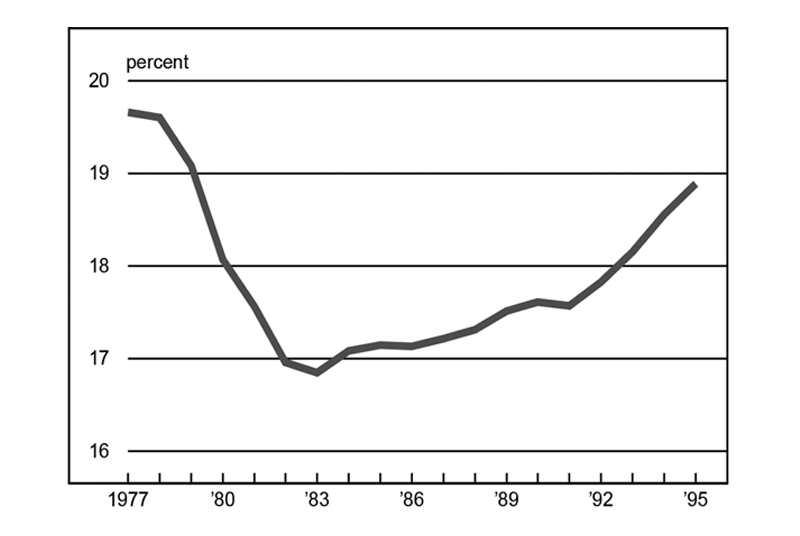

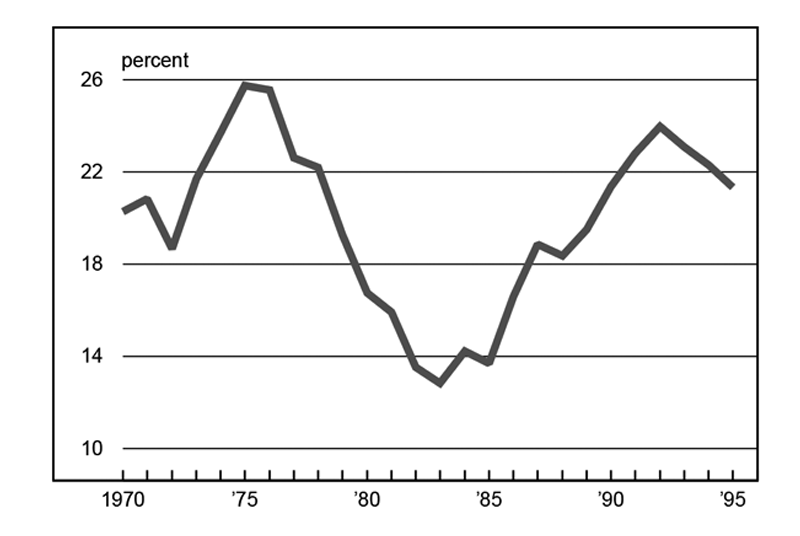

In manufacturing employment, the difference between the national rate and the Midwest rate is even more striking. Midwest manufacturing employment growth has outpaced that of the nation by more than 1.3 percentage points per year since 1988. Last year, manufacturing employment in the region grew 2.3%, compared to national growth of 0.6%. Figure 2 shows the marked increase in the Midwest's share of manufacturing employment since 1983. After bottoming out at 16.9% in 1983, the Midwest's share grew to 18.9% in 1995. While U.S. employment in manufacturing has been virtually flat since 1983, the Midwest has been increasing its employment in manufacturing by an average 1% per year.

2. Midwest share of manufacturing employment

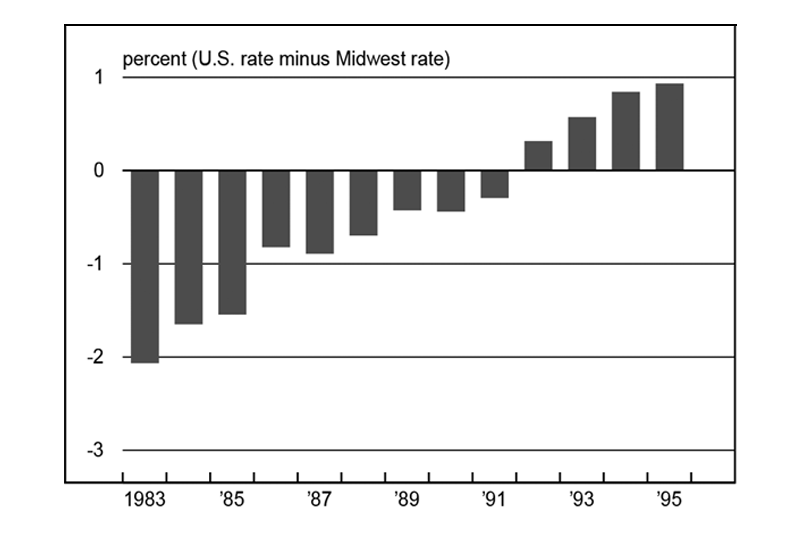

The Midwest's relative strength in employment has translated into very tight labor markets. While the national unemployment rate was 5.6% for 1995, the Midwest unemployment rate was 4.7%. Unemployment rates in the region's major metropolitan areas were also quite low relative to the nation. Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee had 1995 unemployment rates of 4.9%, 5%, and 3.4%, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the strides the Midwest has made toward shining up its Rust Belt image. Between 1983 and 1992, the region went from having an unemployment rate more than 2% higher than the nation's to having an unemployment rate lower than the nation's (for the first time since the middle of 1979).

3. Relative unemployment rate

Signs of tight labor markets in the Midwest can be seen in other measures. For example, the help-wanted index for the Midwest increased by 2.2% in 1995, while the U.S. index increased by only 1.7%. Manpower, Inc. hiring plan data also reflect the strength of the Midwest labor market. The Midwest has had stronger hiring plan numbers than the nation since 1990. In 1995, the net percentage of companies reporting increases was 20.5% for the Midwest, while the national rate was 17%.

Retail sector

In 1995, total retail sales rose 5.7% in the Midwest versus 5.4% in the nation. Midwest durable goods sales were particularly strong, growing 7.8%, compared to 6.7% for the nation. While Milwaukee's retail sales growth matched that of the region, Chicago and Detroit experienced much weaker growth in 1995—2% and 2.3%, respectively.

The Midwest's strong retail sales are reflected in higher levels of optimism among small businesses (see figure 4). In 1995, small businesses in the Midwest had higher index-level growth rates than their counterparts across the nation.

4. Small business indexes

| 1995 growth rates | ||

| U.S. | Midwest | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimism index | 1.8 | 3.8 |

| Current status | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| General expectations | 2.4 | 7.8 |

| Spending plans | 1.4 | 3.8 |

Consumer confidence continued its upward trend last year. National consumer confidence levels have been rising since 1993, recording an increase of 10.5% in 1995. Midwest consumer confidence levels have followed a similar pattern, but with somewhat stronger growth—13.1% in 1995.

Manufacturing sector

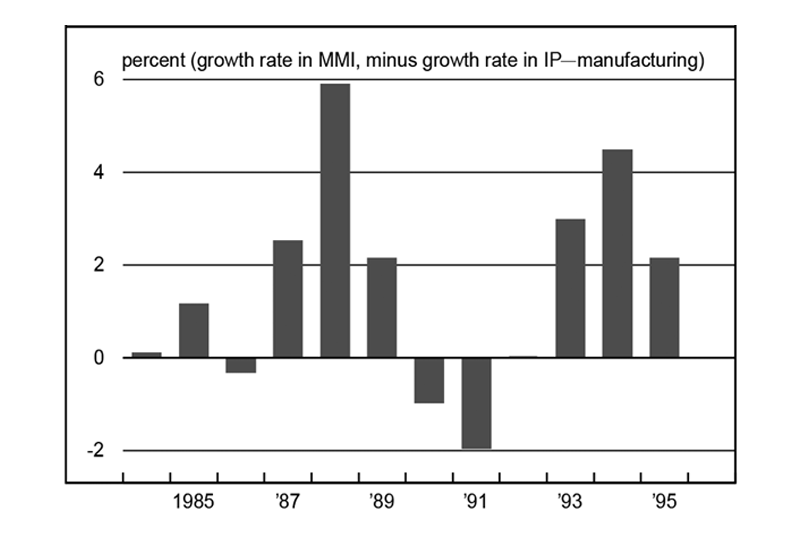

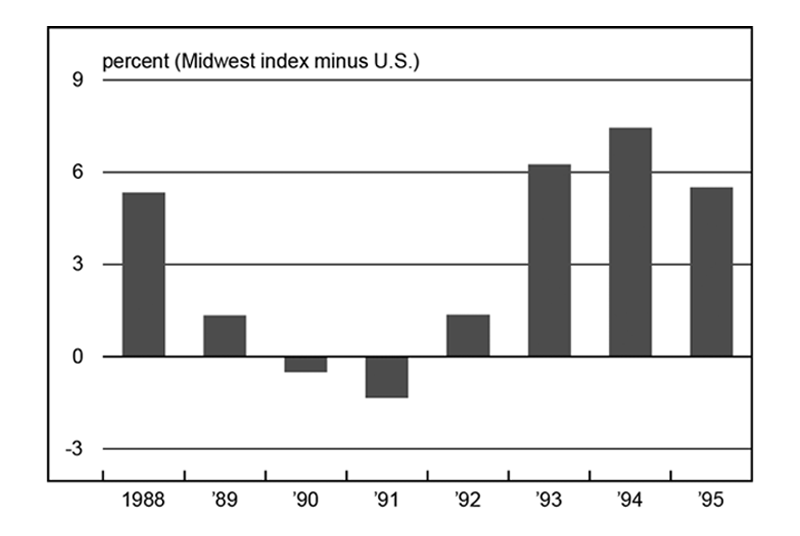

The Midwest's economic prospects are highly sensitive to the performance of the manufacturing sector. Manufacturing in the region has been doing exceptionally well, as is borne out by a regional measure of manufacturing output, the Chicago Fed's Midwest Manufacturing Index (MMI). The MMI rose by 5.7% during 1995, while the Federal Reserve Board's industrial production index for the U.S. manufacturing sector increased by only 3.6%. Since 1992, Midwest manufacturing output has been growing faster than national manufacturing output (see figure 5). However, the differential narrowed during 1995.

5. Industrial output differentials

According to the Midwest purchasing managers' production index for 1995, industrial output in the region outpaced the national average (see figure 6), as it has every year since 1992. Last year, the average level for the index in the Midwest was 56.7%, while the national average was 51.1%. This indicates that the Midwest was experiencing continued expansion, while the nation, just above the 50% expansion-contraction line, was closer to a contractionary stance. However, focusing on several key industries in the Midwest reveals some weakness in manufacturing.

6. Purchasing managers' survey

For example, while auto production nationwide declined by 1.4% in 1995, in the Midwest it dropped by nearly 2.3%. Steel production in the Midwest suffered more from the inventory correction that took place in 1995 than the nation as a whole. National steel production increased 5.4% for the year, compared to a 4.4% increase in the Midwest. National portland cement shipments rose by 3.9% in 1995, while in the Midwest the level of shipments was virtually unchanged from 1994. Finally, while gypsum wallboard shipments were flat for the nation, they fell by nearly 1% for the region.

Housing and construction

The housing market was the only Midwest sector that underperformed overall in 1995 relative to the nation. Mortgage rates had risen more than 2% in 1994, peaking in December at 9.2%. Although rates declined to early 1994 levels by the end of 1995, the high interest rates at the beginning of the year set the stage for a very soft housing market in 1995. Housing starts were off by more than 6% in 1995 for the nation, and by more than 10% for the Midwest. The Midwest's share of total housing starts has been declining since 1992 (see figure 7). Sales of existing single-family homes in the region declined by just over 3%, which was in line with the national trend.

7. Midwest share of U.S. housing starts

The nonresidential and commercial construction market was also weaker in the Midwest than in the nation. Midwest growth in nonresidential construction in 1995 was less than half that of the nation, at 5% compared to 11.2%. Commercial construction growth was even more dismal, with the nation growing by 15.2% and the Midwest actually experiencing a decline of 10.2%. Only manufacturing construction in the Midwest exceeded the national level, increasing by 23.3% compared to 21.7%.

Conclusion

Even though some sectors in the region indicated some weakness in 1995, for the most part the Midwest appears to have had an exceptional year. With some early data for 1996 available, it appears that the Midwest economy is still growing and outperforming the nation in most of the same sectors as last year. For example, for the first two months of 1996, national manufacturing employment averaged a decline of 1.4%, while Midwest manufacturing employment was unchanged. The Midwest share of manufacturing employment increased to over 19%. Midwest housing starts were up 15.1% for the first three months of this year, compared with the first three months of last year. National housing starts grew only 12% for the comparable period.

Looking ahead, most analysts expect the Midwest economy to continue to grow, supported by strong growth in the sectors in which the region has some specialization (such as manufactured goods).

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1987=100)

| March | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMI | 143.4 | 146.4 | 142.3 |

| IP | 125.4 | 126.4 | 124.1 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| April | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cars | 6.3 | 4.7 | 6.5 |

| Light trucks | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

Purchasing managers' surveys: net % reporting production growth

| April | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 55.6 | 49.8 | 59.2 |

| U.S. | 51.9 | 46.2 | 54.4 |

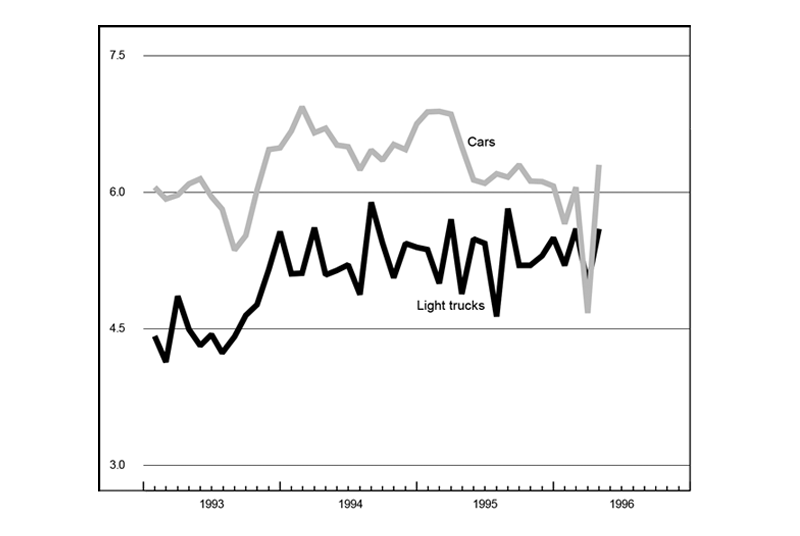

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

Sources: The Midwest Manufacturing Index (MMI) is a composite index of 15 industries, based on monthly hours worked and kilowatt hours. IP represents the Federal Reserve Board industrial production index for the U.S. manufacturing sector. Autos and light trucks are measured in annualized units, using seasonal adjustments developed by the Board. The purchasing managers' survey data for the Midwest are weighted averages of the seasonally adjusted production components from the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee Purchasing Managers' Association surveys, with assistance from Bishop Associates, Comerica, and the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.

Midwest manufacturing activity was boosted in April by a snapback in auto assemblies, following the 17-day GM strike. Light-vehicle production jumped from 9.7 million units in March to 11.9 million units in April. With roughly half of GM's production in Michigan and Wisconsin, the region received a disproportionate impact from the strike. The Midwest Manufacturing Index's drop in March was over twice that of the industrial production index for the nation.

Stronger manufacturing activity led to a sharp increase in the production component of the national purchasing managers' index in April, which returned to a level above 50 for the first time since mid-1995. Purchasing managers' surveys around the Midwest were much higher than the nation on average in April but showed a similar pattern of improvement from March; even the Chicago purchasing managers' survey returned to a level above 50 for the first time in three months.

Notes

1 The Midwest is defined as the states that comprise the Seventh Federal Reserve District, including parts of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin and all of Iowa.

2 When individual state data are not available, the closest matching region is used.