The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

What have we learned from emissions trading programs? The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago recently hosted two one-day conferences that were sponsored jointly with the Acid Rain Division of the U.S. EPA and the University of Illinois at Chicago and organized by the Workshop on Market-Based Approaches to Environmental Policy. The conferences focused on how efforts to improve air quality have incorporated emissions trading programs and what has been learned in the process. This Chicago Fed Letter presents a summary of the discussions.

Role of market-based programs

For more than a decade, regulators have been moving away from command-and-control strategies, whereby a regulator would specify a technology-based standard to apply uniformly to the regulated community, toward market- or incentive-based regulation.1 The environmental sector is one of the key areas where these changes are playing out. This shift to incentive-based regulation has come about largely because of the many problems with traditional command-and-control regulation. One of the most fundamental problems with command-and-control is an asymmetry in information and expertise. Command-and-control regulations tend to require information from the regulated firm that cannot be obtained by the regulator reliably and at reasonable cost. Regulated firms also tend to have far more expertise in how best to achieve the desired goals. As a result, command-and-control regulations are difficult to implement. More importantly, the regulations tend to be far more simplistic than the activity they regulate. Too often, they are “one-size-fits-all” rules that involve a host of cost inefficiencies.

Market-based or incentive-based programs, on the other hand, represent a completely innovative approach. In essence, incentive-based regulation draws on the expertise and self-interest of firms to meet public policy goals. Instead of facing a technology requirement, a firm is constrained by a performance standard. The firm knows how much of the pollutant it can emit during a given period. It is then up to the firm to meet the emissions goal. If it can control and lower its emissions at low cost, it has every reason to control more than is required and sell the difference in the marketplace. The firm will do that until the marginal cost of controlling one unit of pollutant is equal to its market price. Alternatively, it will purchase permits on the market if they are priced below the firm’s own control costs. This approach helps address the asymmetry problems mentioned above. It also helps create a cycle of continuous improvement as firms have an incentive to develop more efficient methods of achieving regulatory goals.

During the two one-day conferences, a group of regulators, industry representatives, policymakers, and academics came together in Chicago to discuss what we have learned from applying environmental trading programs. Robert Stavins, professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, reviewed the lessons from using market-based approaches to environmental protection during the last 25 years. He noted that only recently has the interest in market-based instruments, especially tradable permits, increased noticeably.2 That is despite the overwhelming evidence on the economic advantages of market-based instruments for environmental protection. Stavins attributed the recent surge of interest to a recent increase in awareness and understanding of how market-based approaches work, as well as growing concern about the costs of achieving further environmental cleanliness. With regulated entities facing increasing costs to meet more stringent environmental goals, market-based programs that are more cost-effective in reducing pollution are becoming increasingly attractive.

In conclusion, Stavins offered the following assessment: Most importantly, tradable permit systems work. Secondly, the performance of these programs highlights the great value of regulatory flexibility compared with the rigidity of one-size-fits-all programs.

Specific incentive-based programs

During the course of the two conferences, evidence was presented on several programs to control ground-level ozone as well as on the market for reducing sulfur-dioxide emissions. Joseph Belanger, former director of planning and standards with the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, reported on how Connecticut implemented market mechanisms three years ago by including tradable emission reduction credits in a specific nitrogen-oxide (NOx) emissions reduction program. The market-based elements have been well-received and have improved compliance. Importantly, they have allowed sources a new compliance option. As a result, the agency has started to incorporate these concepts into other programs.

James Lents, director of corporate affiliate programs and environmental policy in the College of Engineering at the University of California, Riverside, and former executive officer of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, discussed the first three years of experience of a program called RECLAIM (Regional Clean Air Incentives Market) that allows the trading of emission credits for NOx and sulfur oxide (SOx) in the Los Angeles basin. At its inception in January 1994, RECLAIM included 390 stationary sources for NOx reduction and 65 sources for SOx reduction. The emissions for each facility in the program have been capped and are being reduced over time, on average by 75% of the initial level by the year 2008.

Trading volume has been robust during the first three years of the program. As of December 31, 1997, 1,200 trades had taken place, involving 244,000 tons of NOx and SOx. This represents an average of 203 tons per trade. According to Lents, the demand for emission credits is expected to exceed supply in 1999 for NOx and in the year 2001 for SOx. That has already been factored in the prices of credits traded. While credits that were used during the first three years of the program were traded at prices well below expectations before the start of trading in January 1994, prices for future vintages of credits show a noticeable increase around the 1999 time frame, when the overall emissions cap of the program is expected to become binding.3

During a panel discussion responding to Lents’ presentation, evidence was presented on how facilities included in the RECLAIM program have been adjusting to the rules of the program. RECLAIM allows a period of 60 days to trade credits after their expiration date, so that individual facilities can balance their books if necessary to meet the imposed emission cap. In tracing the incidence of these types of trades, it turns out that their frequency falls significantly from the first two to the second two years of the program. During the first period, 66% of all transactions involved reconciliation trades. During the second period that percentage dropped to 40%. More specifically, among single-vintage trades, the percentage of reconciliation trades fell from 81% in the first period to 47% in the second (see figure 1). For multiple-vintage trades, the change was from 48% in the first period to 23% in the second. This demonstrates two effects. First, facilities adjusted to a change in the rules issued for RECLAIM. During the 1994 compliance year, a facility was charged so-called emission fees based on its total holdings of RECLAIM trading credits— an incentive to sell unnecessary trading credits during the reconciliation period. That rule has since been changed. Second, the numbers in figure 1 also reveal that individual facilities have learned to actively participate in the market in a forward-looking manner. A larger share of facilities now buy or sell credits to be used in the future, reflecting decisions made at the firm level about the expected need for emission credits.

1. RECLAIM transactions

Finally, there was some discussion as to the technology forcing effects of a market-based program. One would expect an incentive-based program to encourage participating firms to come up with new technological solutions to existing pollution questions. So far, the evidence from RECLAIM on that issue has been mixed. For one, the observed prices for emission credits have been rather low. Therefore, facilities have chosen to more actively maintain equipment or more efficiently manage equipment operations as cost-effective ways to reduce emissions rather than spend capital for new or modified control equipment. However, there are isolated examples of technological innovations that suggest this avenue of reducing emissions might become more important as the prices of emission credits rise. For example, in searching for ways to reduce its NOx emissions, the ARCO refinery in Carson, CA, found out that its NOx and SOx emissions would fall significantly if petroleum byproducts created in the refining process were removed from waste refinery fuels. These fuels were used to supply process heat to the refinery. The solution was to produce polypropylene with these leftover products and thereby remove them as pollutants. In setting up a polypropylene plant at its refinery, ARCO has found a way to reduce emissions and increase profits at the same time.4

The second major market-based program discussed was Title IV of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, which regulates SO2 emissions from electric utilities. Title IV created a national market for SO2 permits, a program that is designed to minimize the cost of reducing SO2 emissions. The industry is allocated a set amount of allowances per year and firms are required in turn to hold one allowance for each ton of SO2 they emit. Allowances can be transferred to other firms or banked for future use. Dallas Burtraw, from Resources for the Future, presented an appraisal of the SO2 cap and trade market. He argued that it has been very successful according to two criteria. First, comparing the costs and benefits of the program, benefits appear to be an order of magnitude greater than costs, especially due to the salutary effects on human health and visibility (see figure 2). Second, the compliance costs have been significantly lower than anticipated. Most important in accounting for low compliance costs has been the fortuitous fall of fuel prices, specifically the decline of prices for low-sulfur coal. According to Burtraw, long-run costs of the program are now expected to be only half of what was anticipated at the outset.5

2. Expected effects in 2010

| 1995 dollars per affected capita | |

| Benefits of Title IV | |

| Morbidity | 4 |

| Mortality | 69 |

| Lake recreation | 1 |

| Recreational visibility | 4 |

| Residential visibility | 7 |

| Costs of Title IV | 6 |

Looking ahead

In applying incentive-based approaches to improve air quality, we often need to consider a regional or national approach. Air quality can be affected by upwind sources; it does not respect state or municipal boundaries. In the case of efforts to control greenhouse gases, which have received considerable attention since the signing of the Kyoto protocol last year, an international approach seems warranted. As William Nordhaus from Yale University argued at the meeting, such an approach might include the international trading of carbon emission rights. According to modeling done by Nordhaus and his associates at Yale, including a trading element in the international effort to reduce greenhouse gases would have a high payoff if efficiently implemented. However, such implementation would be vastly more difficult than any of the applications of market-based trading to date, as it would face problems of definition and administration. Consequently, he suggested it might be best to start such a program with OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries and extend it as the economic and legal systems of other countries mature.

While implementing international trading of greenhouse gas emissions needs to overcome many difficult issues, these result mainly from the international nature of the underlying problem. In the context of regional or national applications of market-based emission reduction programs, by the end of the meeting many participants had agreed that market-based programs can be a very valuable tool in the regulator’s kit. In particular, speakers highlighted the advantage of allowing greater flexibility in achieving the required emissions as a big improvement over command-and-control regulatory programs. In essence, allowing firms to find cost-effective ways to control emissions is what accounts for the success of today’s market-based programs.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1992=100)

| August | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFMMI | 125.9 | 121.7 | 123.2 |

| IP | 132.0 | 129.5 | 127.9 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| September | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cars | 6.5 | 6.3 | 6.1 |

| Light trucks | 5.9 | 6.6 | 6.1 |

Purchasing managers' surveys: net % reporting production growth

| August | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 59.2 | 52.0 | 59.9 |

| U.S. | 50.3 | 49.2 | 62.4 |

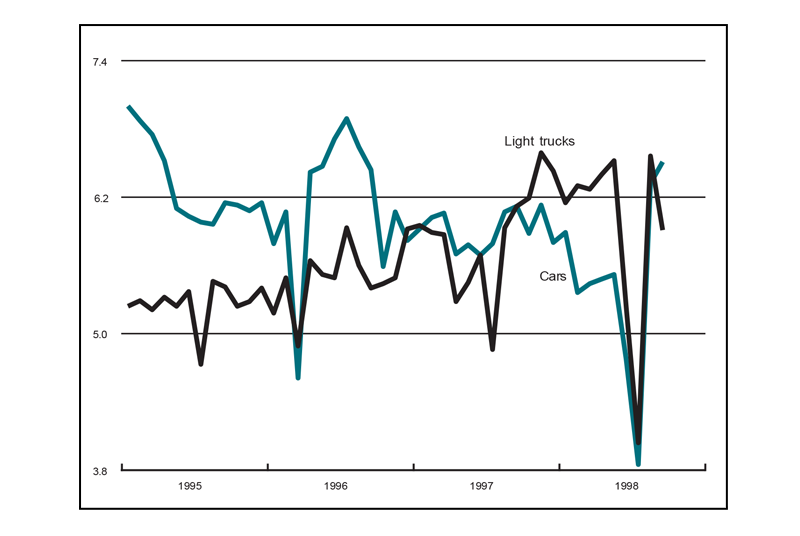

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

Light truck production decreased to 5.9 million units in September from 6.6 million units in August, while car production increased to 6.5 million units from 6.3 million units. The Midwest purchasing managers’ composite index (a weighted average of the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee surveys) increased to 59.2% in August from 52% in July. Purchasing managers’ indexes increased in both Detroit and Milwaukee, but the index decreased in Chicago.

The Chicago Fed Midwest Manufacturing Index (CFMMI) rose 3.5% from July to August, to a level of 125.9; revised data show the index fell 2.1% in July. The Federal Reserve Board’s Industrial Production Index for manufacturing (IP) rose 2% in August after dropping 0.4% in July.

Notes

1 Recently implemented incentive-based regulation will in most cases coexist with command-and-control regulation that had been put into effect some time ago.

2 Tradable permits are one type of market-based regulation. They represent rights to emit a certain amount of a particular pollutant during a specific period and can be traded with other parties.

3 For a more detailed evaluation of the RECLAIM program, see Chicago Fed Letter, August 1997, No. 120. That publication also relates the lessons from the California program to a program that will become effective for the Chicago region during the summer of 1999.

4 James M. Lents, 1998, “The RECLAIM program at three years,” presentation at the workshop Emissions Trading: Lessons from Experience, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, May 15.

5 Dallas Burtraw, 1998, “Appraisal of the SO2 cap-and-trade market,” presentation at the workshop Emissions Trading: Lessons from Experience, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, June 19.