This article examines the current financial health of individuals who experienced a home mortgage foreclosure during the Great Recession and assesses the degree to which they have recovered relative to those who lost their homes before the downturn.

As a result of the severe decline in the housing market and the financial crisis during the last economic downturn, many Americans were unable to make mortgage payments and subsequently lost their homes to foreclosure. We estimate that between 2007 and 2010, there were approximately 3.8 million foreclosures.1 Now, nine years after the onset of the housing bust, we think it is worthwhile to assess the financial health of the individuals whose homes were foreclosed on during this period. Have they regained their financial footing, or are they permanently scarred? How different were their experiences compared with those of borrowers whose homes were lost to foreclosure in the years before the Great Recession? Did their experiences differ by their financial success (as reflected in their credit scores) before the Great Recession? And how likely are they to have undertaken a new mortgage?

In this Chicago Fed Letter, we address these questions by using data on a large sample of individuals who experienced a home foreclosure after 2000, with a focus on those who entered foreclosure between 2007 and 2010. We use credit bureau data through 2016 from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax (CCP) database. We build on prior work by Brevoort and Cooper,2 who also used the CCP database but whose analysis ended with 2010 data. Their study showed that prime borrowers (i.e., borrowers with credit scores 660 and above3) who had experienced a home foreclosure during the Great Recession were especially hard hit and that their rate of recovery was significantly slower relative to such borrowers who had experienced a home foreclosure earlier in the decade. We extend Brevoort and Cooper's analysis through the second quarter of 2016 in order to examine how these patterns evolved over the subsequent years of the economic expansion. Specifically, we examine the entire trajectories of credit scores and credit delinquencies starting from the years before a foreclosure event and also extending many years after foreclosure. We also examine whether borrowers obtained a new mortgage in the years after foreclosure.

Foreclosures surge during the great recession

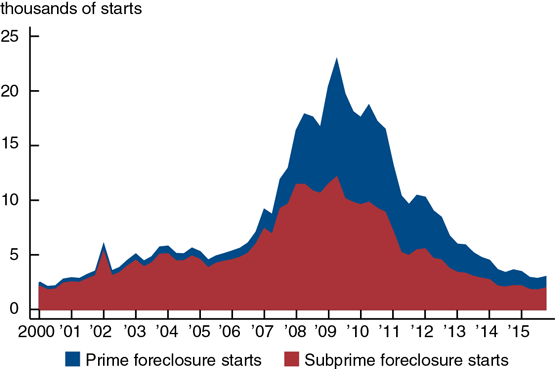

Our data are based on a 5% random sample of the population with credit bureau reports from the CCP database. These data allow us to study patterns in the number of new foreclosures ("foreclosure starts") each quarter beginning with the first quarter of 2000. Figure 1 shows that foreclosure starts were fairly steady until around the end of 2006. They then began to surge in 2007, peaking in 2009. After 2010, foreclosure starts began to rapidly decrease; by the end of 2012, the number of new borrowers entering foreclosure returned to pre-crisis levels.

1. Foreclosure starts, by home mortgage borrower credit status

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

Before the Great Recession, the majority of foreclosure starts were among subprime borrowers (i.e., those whose credit scores were below 660 before they entered foreclosure).4 Figure 1 shows that the Great Recession led to a striking change in the composition of foreclosures between prime and subprime borrowers. According to our analysis, from 2007 through 2010, foreclosures rose approximately 800% among prime borrowers, but only 115% among subprime borrowers. Over the same period, 40% of all foreclosure starts were among prime borrowers and 26% were among borrowers whose pre-delinquency credit score (see note 4) was over 700. This is one defining characteristic of the Great Recession: A much broader range of individuals, including those who had very high credit scores, were swept up in the collapse of housing markets. Indeed, while the overall level of foreclosure starts has come back down to pre-recessionary levels, the fraction of prime borrowers in foreclosure remains relatively higher than it did before the downturn.

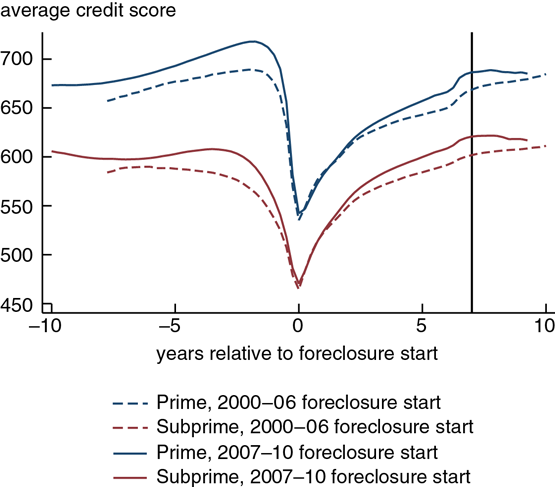

The decline in credit scores at foreclosure

As might be expected, once borrowers enter foreclosure, their credit scores plummet. Figure 2 shows that the declines were very large for both prime and subprime borrowers during the Great Recession (solid lines). The decline in the average score for prime borrowers was about 175 points, and subprime borrowers experienced a decline of about 140 points in their average score.5 Immediately after foreclosure, nearly all borrowers became subprime, with average scores of around 550 for previously prime borrowers and 475 for already subprime borrowers. These declines were a bit larger than those experienced by borrowers who foreclosed between 2000 and 2006 (dashed lines).

2. Credit scores of home mortgage borrowers relative to foreclosure start

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

Recovery after foreclosure

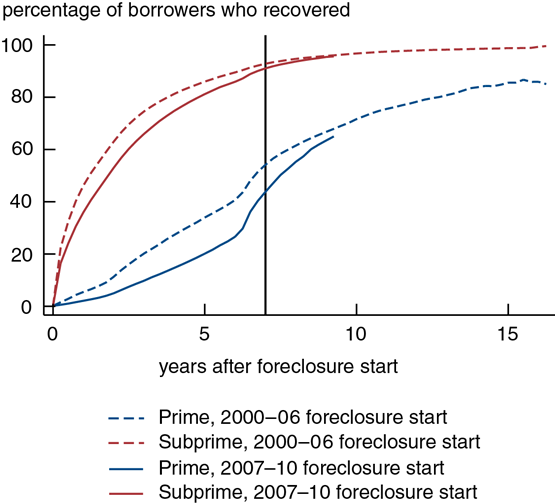

By law, information about any credit payment delinquencies, including mortgage payment delinquencies, must be removed from an individual’s credit record after seven years. Therefore, we would expect that if no other delinquencies occurred, individuals who experienced a foreclosure should see their credit scores recover in seven years. In figure 3, we plot the cumulative fraction of borrowers who reattained their pre-delinquency credit scores (again, see note 4) in the years following a foreclosure and show this separately for previously prime and already subprime borrowers.

3. Share of home mortgage borrowers who recovered pre-delinquency credit score after foreclosure

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

What is immediately evident is that subprime borrowers tend to recover their pre-delinquency credit scores relatively more quickly than prime borrowers. First, let's examine the patterns of recovery for those who foreclosed on a home before the Great Recession. Among subprime borrowers who experienced a foreclosure between 2000 and 2006, roughly 60% reattained their pre-delinquency credit scores at some point within two years of foreclosure and roughly 85% within five years of foreclosure. In stark contrast, only about 10% of prime borrowers who foreclosed on a home in the same period recovered within two years and only about 33% within five years. After seven years, when delinquency flags are removed from their credit reports (as indicated by the black vertical line), about 90% of these subprime borrowers have reattained their pre-delinquency credit scores, compared with only about 50% of prime borrowers. After 15 years, nearly all subprime borrowers have reattained their pre-delinquency credit scores, whereas about 15% of prime borrowers have still not fully recovered. (Of course, subprime borrowers have a much lower pre-delinquency credit score to return to.)

When we examine the experience of the huge wave of borrowers who lost their homes to foreclosure during the Great Recession, we see a much slower pace of recovery. Specifically, among those who experienced a foreclosure between 2007 and 2010, irrespective of their credit status (prime or subprime), the pace of recovery was slower in the first three to five years after foreclosure relative to the pace of recovery among those who experienced a foreclosure in earlier years. However, after seven years, the subprime borrowers who foreclosed on a home in 2007–10 were virtually on track with their predecessor cohorts in terms of recovering their pre-delinquency credit scores. In contrast, even after seven years, prime borrowers who experienced a foreclosure in 2007–10 continued to lag their predecessor cohorts in reattaining their pre-delinquency credit scores. By 2016, the prime borrowers who entered foreclosure between six and nine years earlier (in 2007–10) appear to have recovery rates that are converging with the historical rates of recovery among their predecessor cohorts. When we further break down the analysis by subgroups of prime borrowers (660 to 700, 700 to 750, 750 and higher), we find that the lack of full recovery is mainly driven by those prime borrowers with the highest credit scores before foreclosure.

Other delinquencies and measures of financial health

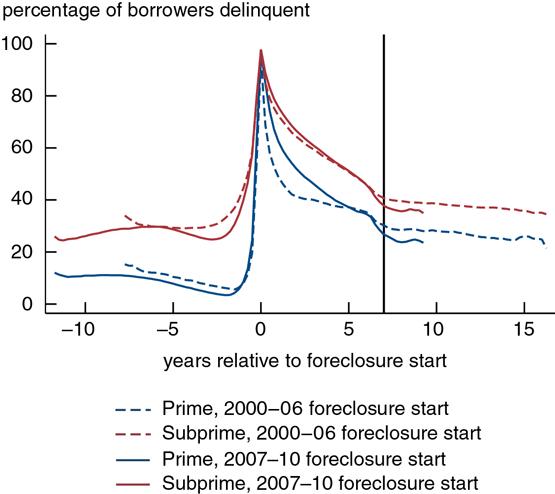

A possible explanation for the slower pace of recovery among those who entered foreclosure between 2007 and 2010 relative to predecessor cohorts is that these individuals encountered difficulties paying their credit obligations on time because of the severity of the Great Recession. Since payment history is a critical component of credit scores, this could explain the especially slow rates of recovery. To address this possibility, we examine delinquency rates on any credit obligations for home mortgage borrowers before and after a foreclosure.

In figure 4, we plot the share of individuals who were 90 days or more past due on one or more sources of credit, including first mortgages, credit cards, and auto loans. Among both prime and subprime home mortgage borrowers, the share with credit delinquencies spikes to roughly 100% at the time of foreclosure and then drops sharply thereafter. Among those who entered foreclosure between 2000 and 2006, the share of prime home mortgage borrowers who are delinquent on their credit obligations tends to decline quite quickly, but never gets back down to the pre-foreclosure levels. Among subprime borrowers, the fraction of those who are delinquent takes much longer to fall, but does eventually get much closer to pre-foreclosure levels.

4. Share of home mortgage borrowers 90 days or more past due on a credit obligation

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

We find that for the first seven years following foreclosure, the share of individuals who were delinquent on any credit obligations among those who experienced a home foreclosure in 2007–10 generally remained higher than this share among those who experienced a home foreclosure in 2000–06. This was the case regardless of the credit status (prime or subprime) before foreclosure. However, after seven years, this pattern reversed.

Implications for the housing market

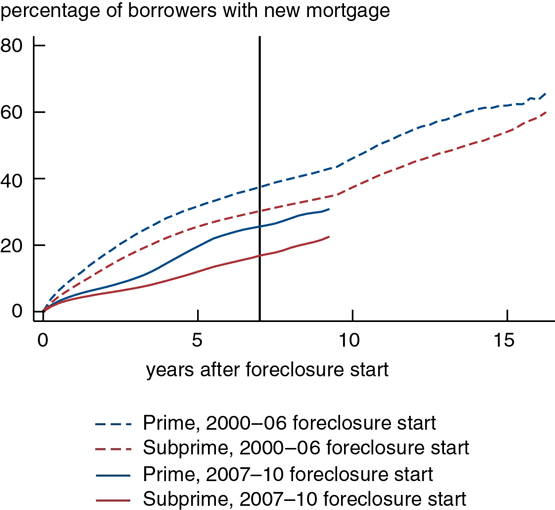

A question of interest is how the experience of foreclosure has affected housing markets. In figure 5, we show the cumulative fraction of individuals who experienced a home foreclosure but who then managed to take out a new mortgage afterward. When looking at the historical experience of prime home mortgage borrowers who entered foreclosure between 2000 and 2006, we find that just shy of 40% took out a new mortgage in the seven years following. The comparable value for subprime borrowers is notably lower, at around 30%. Among those who foreclosed on a home between 2007 and 2010, the shares with new mortgages seven years after foreclosure are dramatically lower at just over 25% for prime borrowers and just under 17% for subprime borrowers.

5. Share of home mortgage borrowers with a new mortgage after foreclosure

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

These findings suggest that even though the overall credit scores and shares of delinquent borrowers appear to have returned to levels closer to historical norms for individuals who experienced a foreclosure in 2007–10, their homeownership rates continue to considerably lag the homeownership rates of those who experienced a foreclosure in 2000–06. The slower financial recuperation of those who lost their homes to foreclosure during the Great Recession has been one important factor behind the slow recovery in housing markets during the current economic expansion.

Summary

By tracking a sample of home mortgage borrowers who entered foreclosure in 2000–06 and 2007–10, or before and during the Great Recession, we find that the pace of recovery in credit scores was slower in the first few years after foreclosure for the latter cohorts. We also find that prime borrowers who experienced a foreclosure during the downturn were especially hard hit and had the most difficulty recovering. Overall, at least 15% of all prime borrowers have permanently lower credit scores regardless of when they foreclosed on their homes. A significant factor behind the slow recuperation in credit scores for borrowers who lost their homes to foreclosure in 2007–10 was adverse economic conditions during the recession, which led to delinquencies on other credit obligations. The slow rehabilitation of their financial health helps explain the slow recovery in housing markets post-recession. Indeed, following foreclosure, these borrowers have considerably lagged their predecessor cohorts in terms of homeownership rates.

1 Authors’ calculations based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax (CCP) and statistics from RealtyTrac (as cited in http://blog.credit.com/2015/04/boomerang-buyers-is-there-homeownership-after-foreclosure-114803/). Because of the high incidence of foreclosures in 2010, we include them in our analysis of foreclosures during the “Great Recession.” The recession officially ended in 2009 according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

2 See Kenneth P. Brevoort and Cheryl R. Cooper, 2013, "Foreclosure's wake: The credit experiences of individuals following foreclosure," Real Estate Economics, Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter, pp. 747–792.

3 Credit scores (FICO scores) have a range of 300–850; for more details, see http://www.myfico.com/credit-education/credit-scores/.

4 We categorize prime and subprime foreclosures based on the credit score of the borrower (prime, 660 and above; subprime, below 660) in the nearest quarter in which there is no major mortgage delinquency (i.e., less than 30 days past due) before the foreclosure start. In the text, we refer to this particular measure of the credit score as the "pre-delinquency credit score."

5 We calculated these declines by taking the difference between the peak average credit score before foreclosure and the average credit score at the time of foreclosure.