Redefining the Challenges and Opportunities for Banks in LMI Neighborhoods Throughout Chicago: Results from Community Capacity Discussion Groups

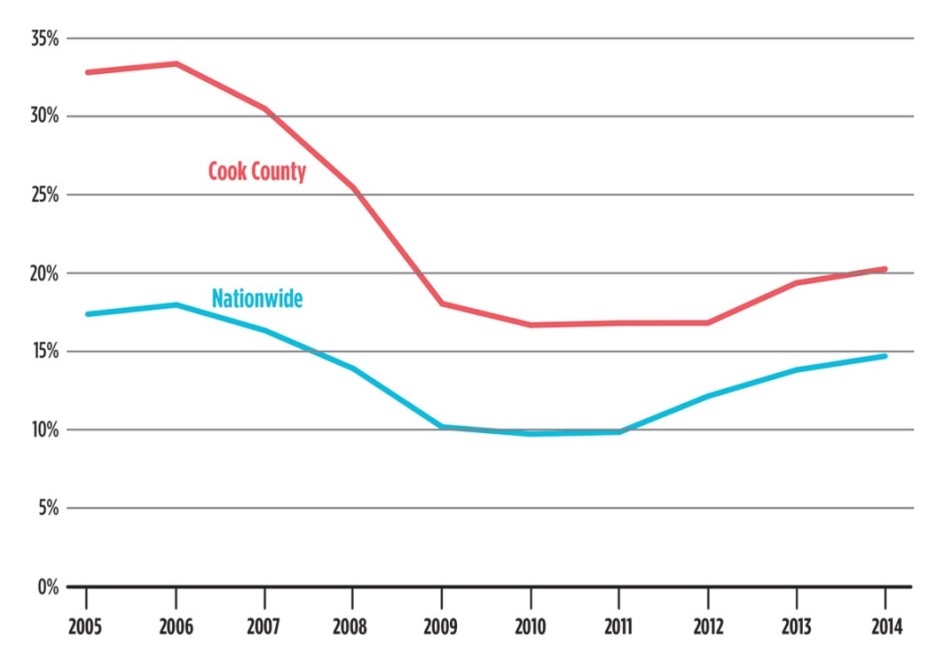

Bank lending in low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods in the Chicago area has remained well below levels that preceded the Great Recession in 2008. Mortgage loans originating in LMI neighborhoods fell from a high of 33 percent of originations in Cook County in 2006 to a low of 17 percent in 2010 (chart 1), followed by a gradual upward trend to roughly 20 percent in the most recent data. According to 2014 CRA small business lending data, small business originations in Cook County (for businesses earning less than $1 million) were still about 45 percent below peak levels in 2007.

This summer, the Community Development and Policy Studies (CDPS) department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago partnered with the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP)1 to bring together more than 20 bankers to share their perspectives on what drives lending and investment trends in their respective markets, and what local banks are doing to increase lending activity in LMI neighborhoods.

1. Percent of HMDA originations in LMI areas

Note: Includes all single family loans, including refinance, home improvement, VA and FHA

Industry analysts have put forward several explanations for why bank lending (both mortgage and small business lending) has not recovered to pre-recession levels in metropolitan areas around the country, including Chicago. These include fewer homebuyers entering the market, a decline in the value of real estate that collateralizes small business loans, soft sales at small firms, and an elevated level of supervisory stringency at banks, among other reasons. The bankers who participated in the roundtable discussions, including representatives from large and small banks, city and suburban institutions, as well as mission-focused, minority-owned banks, and community development banks, offered their own assessments of the factors that have constrained lending in LMI neighborhoods. This blog summarizes participants’ reflections on the challenges to financial inclusion following the Great Recession, and describes the approaches many have taken to promote outreach and services to diverse communities.

Conditions that impact lending in LMI neighborhoods

"Innovation used to be rewarded; now bank boards want to avoid risk."

Many bankers who attended these sessions agreed that the financial crisis reframed their – or their boards’ – perceptions of product risk. Some bankers acknowledged that they have backed away from innovating products for non-traditional customers, such as second-chance transaction accounts and banking products for ITIN holders, out of concern that examiners (as well as their own boards) may not take a positive view of the potential risks associated with these products. Other bankers have moved away from making smaller, higher-cost loans. Some banks have even begun to scale back on their conventional, single-family mortgage lending because of new mortgage regulations including the TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure rule,2 which further establish that failure to comply could restrict banks from accessing the secondary market.

“We can talk about how great it is to make loans in these communities, but if borrowers don’t meet credit standards, there is nothing we can do about this.”

The bankers also noted that the risk profiles of many potential borrowers do not meet the credit standards of their institutions. As many banks have tightened underwriting standards since the Great Recession, mortgage lending has fallen for borrowers in the lower percentiles of the credit score distribution (chart 2). The same trends that are playing out at the national level are taking place within the Chicago metro as well. According to focus group participants, the banks with a strong presence in LMI areas focus on borrowers “with strong balance sheets” who often do not live in the areas where they purchase and develop properties.

2. Mortgage origination volume by risk source — in billions of dollars

In addition, bankers said that many income-constrained households are carrying greater amounts of student debt, which further impedes banks' willingness to approve mortgage credit. A few of the business-oriented bankers also explained the decline in business lending due to small business owners undermining (often inadvertently) their own creditworthiness by underreporting earnings, or not organizing their financial paperwork in accordance with conventional standards.

"Homeowners in many of these neighborhoods are underwater."

Negative equity is another major obstacle that bankers feel has limited the supply of credit in LMI neighborhoods. Although home prices have returned to early-2000s levels in many neighborhoods in the Chicago metro area, in many others, including those on Chicago’s south and west sides, prices are as much as 30 percent below where they were in 2003 and 2004.3 In turn, sagging home prices have reinforced trends of economic stagnation and decline. According to participants, negative equity prevents homeowners in certain neighborhoods from selling their homes, inhibiting churn in those markets, and further weakening home prices in those communities. When homeowners in these neighborhoods look to refinance their mortgages, bankers can do little to overcome high loan-to-value ratios, even with federal programs like the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) that was designed to help struggling homeowners remain in their homes. Negative equity also affects housing supply. If people are not selling their homes, the market in those neighborhoods is stuck because there are fewer homes for people to buy.

In addition, even with negative (home) pricing/valuation pressures, participants reported that homeownership remains unaffordable for many potential homebuyers in lower-priced neighborhoods, despite programs for facilitating the purchase of foreclosed and vacant properties. Although many programs exist for moving new homeowners into vacant properties, such as the Cook County Land Bank and the South Suburban Land Bank, municipalities that support these efforts often do not coordinate with their tax departments, putting so-called affordable properties out of reach for many families due to large outstanding property tax dues.

How bankers reach out to customers in LMI areas today

Increasing Transactional Opportunities

Bankers’ attempts to promote financial inclusion have emphasized the creation of more opportunities for transactional relationships with nontraditional customers. Some banks talked about offering “second chance” accounts that allow people who have been flagged for account mismanagement in the past to open a deposit account. Some banks use prepaid cards to market their institutions to people who customarily have not been comfortable with banks, and sometimes pair these cards with savings accounts. Some offer remittance products (often through third parties) as a way to incentivize people to utilize bank branches. Other banks have offered small loans, though bankers report greater demand for this product on the consumer side than on the business side.

Supporting Financial Education

Banks have also focused on improving customers’ overall preparedness to borrow money. Many banks see financial education as the key to broader financial inclusion since, in the view of many participants, a lack of financial sophistication hurt many borrowers during the financial crisis. Participants explained how they offer education on managing bank accounts, basic budgeting, and home-ownership, usually in conjunction with a community-based organization. The short-term goal of these classes and workshops, according to many of the bankers, is to build trust and relationships through partnerships with nonprofits and grassroots organizations. The longer-term goal is to prepare potential borrowers to qualify for mortgages, rate-reductions, or credits on their loans. For single-family mortgages, banks work with community partners or the public sector to offer down-payment assistance (in the form of grants and forgivable loans from third parties, some of which are place-specific), allowing people to have immediate equity.

Eyeing New Opportunities for the CRA

Some participants see greater potential to support LMI communities through activities outlined in the final revisions to the “Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment” (the Q’s and A’s) published in July 2016. This document, assembled by the federal bank regulatory agencies with responsibility for CRA rulemaking, clarifies and updates a broad set of CRA-eligible activities in addition to traditional mortgage and small business lending. For example, the new guidance offers examples of what is meant by economic development, innovation, and revitalization/stabilization as it is used in the CRA. Such examples include funding programs that (1) create or improve access to jobs or job training for LMI populations; (2) capitalize infrastructure projects, such as broadband internet service and flood control measures; or (3) back loans to finance projects that promote renewable energy or energy efficiency. Further, financial institutions that use alternative credit histories to evaluate credit worthiness, such as rent or utility payments, may also now be considered under the CRA. As these examples illustrate, the revised guidance is designed to reflect both current economic conditions and today’s regulatory landscape; and regulators continue to encourage financial institutions to be open to innovative practices that promote the adoption of bank services in all types of markets.

Conclusion

The impact of the Great Recession continues to influence current lending trends in the Chicago metro area and efforts to promote financial inclusion, according to bankers who participated in the CDPS and CMAP discussion groups. As banks adjust their policies and perceptions to address these challenges, the recently published Community Reinvestment “Q’s and A’s” has the potential to broaden the type of lending, investing and other services that banks provide to LMI communities. The revised guidelines make clear that bankers are valuable partners in responding to unmet market needs.

Footnotes

1 CMAP is the official regional planning organization for the northeastern Illinois counties of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Kendall, Lake, McHenry, and Will, and as part of its comprehensive plan for the Chicago region, ON TO 2050 — the agency is exploring new policy directions for promoting inclusive economic growth.

2 Truth in Lending Act (TILA) – Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA) Integrated Disclosure Rule, also known as TRID, became effective for most loans applied for on or after October 3, 2015. The rule changed the definition of an application, clarified responsibilities for providing forms, established tighter limits on fee spreads, and installed a three-day review period between the closing disclosure and consummation of the loan

3 See Institute of Housing Studies at DePaul University data, available online.