Global Agriculture Conference

On average, rural America has not been faring as well as metropolitan America in terms of population and income growth. Is this trend yet another painful adjustment that can be attributed to globalization?

Globalization policies continue to be closely intertwined with agricultural markets, which have been the historic lifeblood of rural communities in the Midwest. Last month, the Chicago Fed held a conference on “Globally Competitive Agriculture in the Midwest.” The event included the Midwest release of a task force report by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Modernizing America’s Food and Farm Policy. Conference discussion concerned how current global trends and policy debates are affecting agriculture and rural communities, and how prospective policies such as the next Federal farm bill and the Doha round of the world trade talks might play out.

During the conference discussion, several presenters expressed the opinion, without challenges from the audience, that globalization was in some way responsible for the lagging economic performance and stark challenges facing the rural Midwest. However, I think that it is somewhat mistaken to confuse globalization with technological advances and associated structural changes now taking place in the production of agriculture.

First, to concede some ground to the opposition, several forces of globalization have hastened structural adjustments taking place in smaller towns and rural communities. In particular, an expansion of the world market for goods and services has sharpened the economic specializations of many countries and their subnational regions. For the U.S., as global markets in goods, services, and capital have been opened up, the domestic economy has shifted away from manufacturing production and less-skilled services such as back office processing, some software production, and call center activity in favor of advanced services such as finance, investment, and management. For such advanced services, the large urban form, rather than the smaller city or rural town, is the more productive and favorable locale. This preference of industries performing such advanced services has contributed to the growth of large metropolitan areas, such as New York, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and San Francisco.

Aside from that, there is little to argue about globalization as a detriment to rural economic growth. And even at that, I would argue that technological advancements, rather than globalization, account for most of the structural changes that are moving us toward an advanced services economy in the U.S. New technologies, particularly their adaptation in wireless communication and in advanced computing, are highly complementary to such service production, with or without globalization. This is evident the world over as wages, salaries, and employment opportunities have risen sharply for those workers who have the education and technical skills to work with advanced communication and technical tools.

While rural areas have not fared as well in advanced services, the net effects of globalization on commodity production and income in rural areas are mixed rather than one-sided. In much of rural America, the local economy is highly dependent on commodity agriculture or on commodity materials such as energy products, minerals, and timber. Here, relentless productivity advances, especially in agriculture, have obviated the need for as much labor as in the past. In turn, lessened labor demand has put pressure on rural growth.

Yet, such labor substitution is hardly related to globalization. It is true that global markets can introduce competition into commodity markets. Yet, on the flip side, falling transport costs and more open markets also increase possibilities for heightened exports and firmer prices for the commodities produced in rural areas. In the Midwest, for example, global exports in soybean and corn have helped to sustain jobs and income. More recently, as developing countries have improved their diets, U.S. exports of beef, pork, chicken, and poultry have grown. Here, the competitive advantage in grain production translates into local livestock production. The processing of grains and livestock (in order to shed weight and volume before exports) is kept close to the location of grain and livestock production, that is, rural communities.

Growing global growth has also boosted prices of carbon-based fuels. As a result, exploration, mining, and production of fuel sources are providing more jobs and lifting income in many rural communities. In corn-producing states, federal subsidies have combined with rising prices of fossil fuels to spur rapid expansion of corn-based ethanol capacity as a viable energy source. As a result, prices for corn have been raised and are expected to remain so. Moreover, ethanol plants are being built near corn production in rural communities, thereby boosting associated manufacturing jobs.

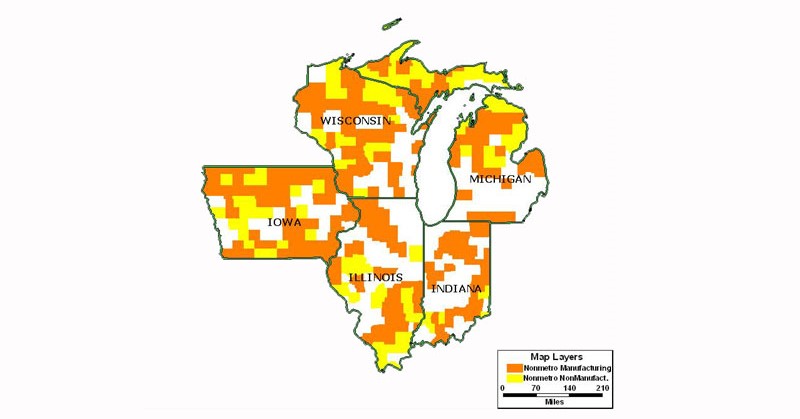

But ethanol production has not been the only source of manufacturing jobs in rural communities. In the Midwest, as shown below, rural and nonmetropolitan counties have been gaining share of manufacturing jobs at the expense of metropolitan counties for several decades. There are several reasons for this shift, but the dominant factor points to technological changes in production. In particular, areas with lower population density are favored for many types of production due to easier transportation access and lower land costs. And if these forces have been accelerated by global competition, rural areas are the beneficiaries. Income from manufacturing is replacing income earned on farms as the dominant economic base across the Midwest.

Figure 1. Manufacturing job growth in the Seventh District, indexed to 1969

Table 1. Non-metropolitan employment

Source: BEA

Of course, rural communities in the Midwest face many challenges in the years ahead. For one, manufacturing production centers sited in rural communities are highly vulnerable to global competition. So, too, commodity prices have historically been volatile such that commodity-based economies have often been whipsawed by downward price swings. Global markets show no promise of easing the variability of commodity price swings.

For these reasons, rural communities are striving to avail themselves of development opportunities as they present themselves. On October 24–25, 2006, the Chicago Fed will be partnering with Iowa groups on an informational conference in Ames, Iowa, called “Expanding the Rural Economy through Alternative Energy, Sustainable Agriculture, and Entrepreneurship.”

The question of whether globalization has been a net plus or a net negative for rural areas is not an easy one. Yet, more than ever, rural communities will want to stay closely attuned to trends and policies related to global affairs.