Chicago’s Pursuit of the Global Prize

Policy and business leaders in Chicago continue to advance the metropolitan area’s prospects as a global hub for professional and financial services. This initiative arises from both necessity and opportunity. Chicago’s traditional markets, principally in the surrounding Midwest, are not growing rapidly. At the same time, however, the Chicago economy specializes in advanced producer service sectors that are increasingly traded more broadly and, in many cases, internationally.

As the business service center of the Midwest, serving regional markets and industries, Chicago companies’ prospects for growth are somewhat limited. That is so largely for two reasons. First, the Midwest economic base centers on agriculture and manufacturing. Since productivity growth is so very high in these industries, and competition keeps commodity prices low, income and revenue (and attendant jobs) grow slowly. The second reason is climate. As the U.S. economy restructures toward information industries and knowledge workers, service production is being pulled toward locations where workers prefer to live, often milder climes.

However, globalization of the economy has also brought new opportunities to populous information-based cities like Chicago. Large cities often have wonderful amenities that are not dependent on climate, such as sports, restaurants, museums, and cultural diversity. But more fundamentally, it is because expanding global trade in goods, services, and capital requires the complex and specialized functions and industry sectors that are concentrated in large cities, including legal services, logistics, distribution, finance, insurance, business meetings, R&D, and professional business services.

Chicago has been developing such sectors almost since its inception. Today, Chicago features world-leading risk exchanges, universities, business meeting and personal air travel firms, legal services, headquarters facilities, and management consultancies.

During the 1990s, the growth of Chicago’s professional services was robust. According to the data reported on payroll employment, the Chicago metropolitan area added a net 80,000 jobs in the sector from 1990 to 1999, more than the Los Angeles metropolitan area and more than New York City.

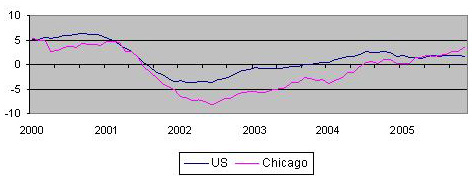

However, since then, job performance in Chicago has often been much weaker, raising doubts about whether the city’s economic structure has divorced itself from the surrounding region as much as previously believed. The chart below displays year-over-year growth in the professional, technical, and R&D sectors. Employment growth experienced year-over-year declines for most of the 2002-2004 period, before reviving in 2005.

1. Professional, scientific and technical services — year over year job growth, January 1990-November 2005

How much of Chicago’s business service economy has expanded to global markets or even to other large U.S. cities in the global network?

We know very little about the geography and changing geography of these hallmark industry sectors. However, one informative study by Peter J. Taylor and Robert E. Lang of the Metropolitan Policy Program at The Brookings Institution measures the prominence of major global service companies among large cities in the world.

Taylor and Lang examine 100 global companies drawn from the business or producer sectors of accounting, advertising, banking/finance, insurance, law, and management consulting. For each city, the sum presence of their offices (weighted by size and function) determines a score for a city’s commercial presence and ties to the global city service network.

According to the Taylor-Lang study, Chicago scores high in its global connectivity, both relative to other U.S. cities and relative to the world’s major cities. Among U.S. cities, Chicago ranks second only to New York. Among world cities, Chicago ranks seventh, behind London, New York, Hong Kong, Paris, Tokyo, and Singapore.

The Taylor-Lang study scores Chicago’s connections with domestic cities such as Atlanta and New York in the same way it scores connections with international cities such as Sydney. This seems correct. International borders can be arbitrary. And to otherwise score border-crossings might bias the results toward cities located on continents where national boundaries are near each other, such as Europe.

The study does provide a separate “hinterland” scale for each city, which tries to measure the degree to which a city’s global connectivity relies on nearby national trading relations. Here, with the exception of New York City, U.S. cities tend to be less international than those on other continents. However, Chicago again scores well. It places third among U.S. cities, behind New York and Miami.

How this relates to Chicago’s recent growth performance and prospects is not clear. The construction of the Taylor-Lang study is creative, clever, and somewhat revealing, but it provides more impressionistic than definitive evidence of global linkages among producer services. Those who would like to draw their own conclusions from the evidence should take a look at the authors’ map of each global city’s linkages, including Chicago. Outside of North America, for example, the map suggests that Chicago’s economy links strongly with Zurich, Switzerland, and Sydney, Australia.

Chicago’s employment in business-professional services is once again growing strongly, at a 3% annual year-over-year pace. If the recent period of weak performance reflects some unusual and fleeting conditions such as a post 9-11 falloff in business travel and related business service activity, then perhaps Chicago’s march to global success will now continue.