Transportation and GHG regulation

On October 15, the Detroit Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago will convene a conference examining various policy approaches to reducing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHGs). Following electric power generation, the transportation sector is the second largest source of carbon dioxide emissions in the Midwest, as well as in the overall U.S. (Carbon dioxide emissions generally arise from the burning of fossil-based transportation fuel—gasoline more so than diesel fuel.)

Following the energy price spikes of the early 1970s, federal regulations were issued to improve fuel-efficiency of cars and light trucks. Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations place fleet-wide fuel-efficiency limits on manufacturers for their passenger cars and separate standards for their light trucks (including so-called minivans and sport utility vehicles, or SUVs).

The CAFE standards are sometimes credited with maintaining fuel-efficiency during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, when gasoline prices plummeted and one might have otherwise expected vehicle size and fuel consumption to have grown once again. Nonetheless, CAFE standards are often criticized. For one reason, the added cost of introducing new fuel-efficiency technologies into the latest models may be counterproductive. That is because, in confronting higher vehicle costs, automotive buyers may delay scrapping their old vehicles, thereby keeping an older (and less fuel-efficient) fleet of vehicles on the road.

Fuel-efficiency standards have also been criticized for imposing unnecessary and distorting restraints on consumers’ choices of vehicles. Logically speaking, penalties to modify behaviors to align with socially desirable outcomes should be fashioned to most closely target those behaviors that give rise to social costs. Accordingly, rather than forcing fuel-efficiency standards on specific types of vehicles, a preferable approach would be to penalize the actual behaviors that give rise to carbon emissions regardless of vehicle type. That is, a tax on fuel at the pump would be preferred to vehicle fuel-efficiency standards. And a tax per unit of carbon associated with a particular fuel—such as gasoline over diesel—would be preferred to a general fuel tax. Nonetheless, to date, fuel-efficiency regulations have been more palatable to the American public than alternatives such as direct gasoline taxes.

Midwest-domiciled automakers, especially the Detroit Three (Chrysler LLC, Ford Motor Co., and General Motors Corp.), have so far found it more difficult than other manufacturers to achieve CAFE fleet standards on cars and light trucks. Going back to the 1970s and earlier, Detroit Three automakers have tended to offer larger vehicle models for sale, and this specialization has continued into recent years.

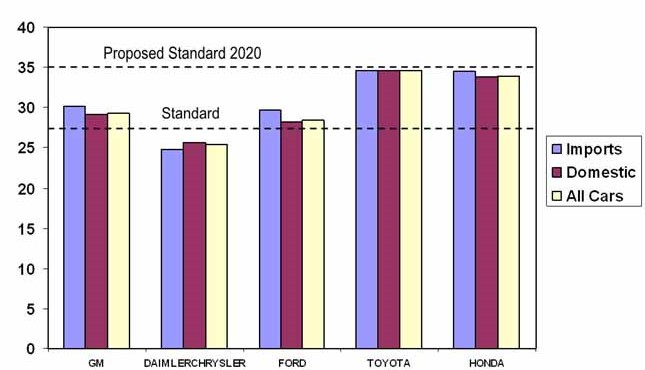

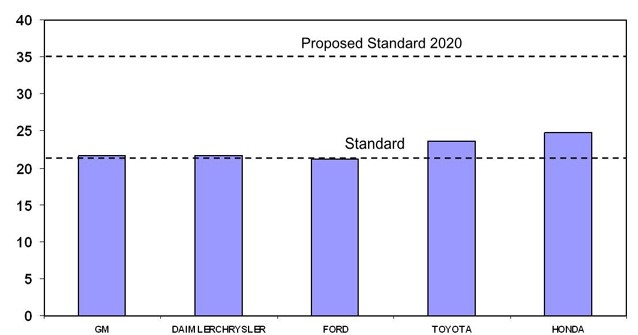

The figure below displays the reported average fuel economy in 2006 for major companies selling vehicles in the U.S. market. For both passenger cars and light trucks, the measures of fleet average fuel-efficiency for both Toyota and Honda easily exceed those of the Detroit Three. Indeed, for passenger cars, the fleet fuel economies of Honda and Toyota already approach the hypothetical standard that is being considered for the year 2020.

1. Fuel economy of passenger cars in 2006

2. Fuel economy of light trucks in 2006

CAFE standards may soon become even more onerous for automakers. In June 2007, the U.S. Senate passed legislation mandating stricter standards on both passenger cars and light trucks. By the year 2020, fuel-efficiency standards would rise for such vehicles so that they must achieve 35 miles per gallon. (Such revised CAFE standards will likely be considered by the U.S. House of Representatives during the fall of 2007).

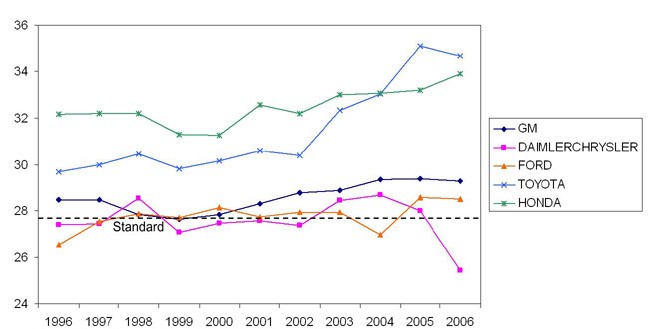

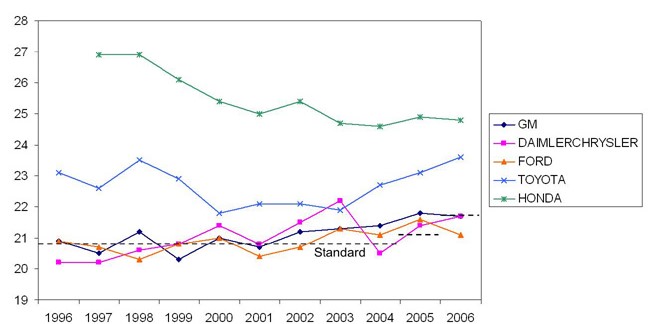

The vehicle fuel-efficiency of major automakers has been changing in recent years. Per the figure displaying the fuel economies of passenger cars below, Toyota’s and Honda’s have gained markedly over those of the Detroit Three during the decade. In contrast, these Japanese automakers have not widened their fuel-efficiency advantages in the light truck category. Within the category, Honda and Toyota have been selling more models that are heavier and less fuel-efficient than they had before; these models would include the Honda Pilot and Toyota Land Cruiser SUV.

3. Fuel economy of passenger cars, 1966-2006

4. Fuel economy of light trucks, 1966-2006

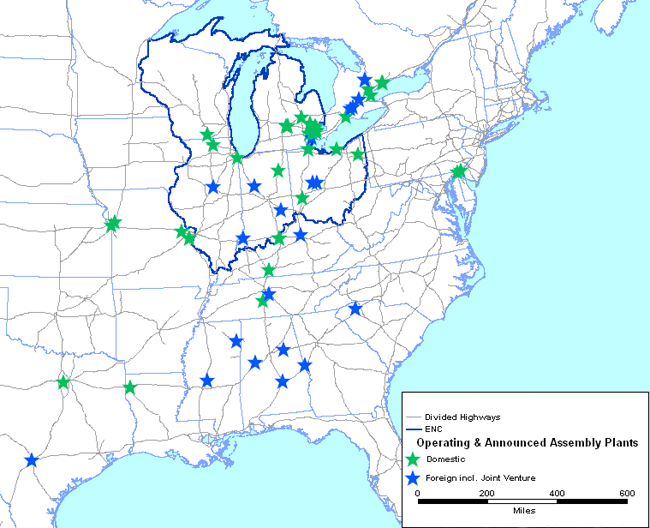

From a Midwest perspective, the region’s light vehicle production facilities tend to be those of companies that will likely find it most difficult to meet more stringent standards. The map below displays the assembly plant locations of the Detroit Three automotive companies, as well as those of the foreign-domiciled automakers. A large majority of the Detroit Three’s light vehicle production facilities are located in Midwest states. In the northern part of the U.S. automotive corridor, which includes the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Missouri, 24 of its 31 light vehicle plants are owned by the former Big 3 domestics. Accordingly, the region’s residents will be interested to see that any prospective carbon reduction policies are as cost-effective as possible.

5. Light vehicles

Not everyone believes that GHGs from human activity are significantly contributing to global climate change or, if so, that mitigation policies are advised. Still, it would appear that mitigation policies, including more stringent CAFE standards, will be forthcoming. An informed and judicious choice of alternative policies can contribute to achieving cost-effectiveness while reducing GHG emissions.