Chicago Business Cycles–Now and Then

Downturns in economic conditions often come as a surprise. In fact, time lags between statistical releases and the conditions that they reflect can mean that economic slowdowns are not known until months after they have begun. Statistical information covering individual reasons tends to be worse in this regard.

Today there is, however, a widely held view that the U.S. economy has slowed sharply and that economic conditions will not immediately improve. Broad-based measures of national economic activity, such as the Chicago Fed National Activity Index (CFNAI), indicate that U.S. economic growth is well below its historical trend. As a result, observers in regions such as the Chicago metropolitan area are preparing for hard times. And they are asking whether they are likely to feel the worse for this apparent slowdown—and how long it will last.

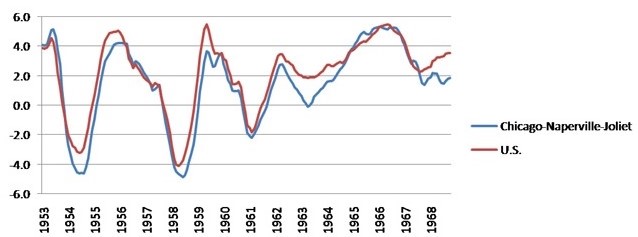

In the Chicago area, memories are becoming dim of those days when the pace of the local economy fell sharply in response to national economic downturns. However, the chart below should remind us or inform us anew of the fact that Chicago’s economy often experienced sharp swings in employment. In the past (especially before 1990), Chicago’s employment base had been steeped in durable goods manufacturing industries, such as machinery and steel, which experienced layoffs and downsizings when the national economy turned downward. Twice during the 1950s, Chicago area payroll job declines approached 5 percent on a year-over-year basis as national job declines reached 3 and 4 percent on those two occasions. Chicago fared little better during the recessions of 1970–71, 1974–75 and 1981–82.

1. Total nonfarm employment – Chicago MSA vs. U.S. (3-month moving average percent change year over year)

Given this track record, it may seem pointless to ask how the region’s economy will fare in the months ahead. However, the question is well considered both because the economic structure of our economy is always changing and because no two economic downturns are alike with respect to their causes and impacts on industries.

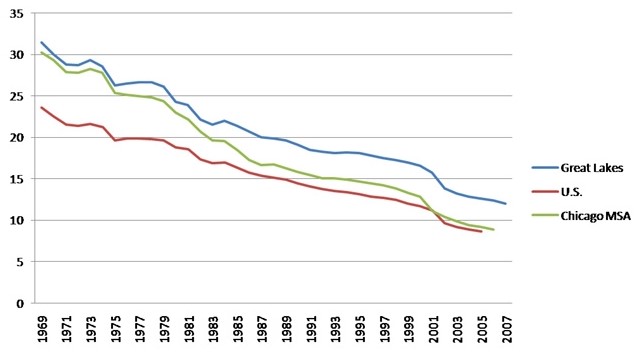

Chicago’s economy is continuing to restructure in several important ways. Most dramatically, the region’s employment structure no longer concentrates directly in manufacturing. As recently as 1969, 30% percent of the Chicago metropolitan statistical area’s employment could be found in manufacturing in comparison with 24% for the overall U.S. By 2005, manufacturing’s share of employment had fallen to 9% percent and it had converged with the U.S.’s percent share. At least this element of sensitivity to national business swings seems to have partly abated.

2. Manufacturing share of total jobs

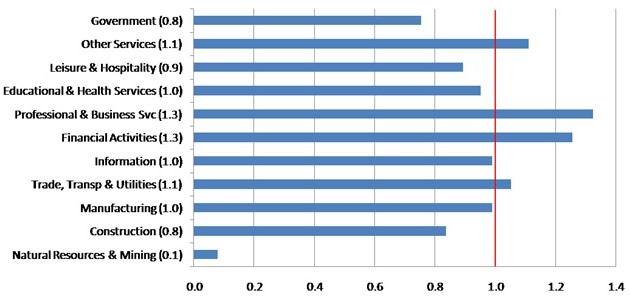

At the same time that manufacturing has waned, the Chicago area has also restructured into higher-order professional services, business meeting and travel, and financial services. (The chart below indexes the Chicago area payroll employment by major industry sector. An index value greater than 1, for example, indicates that Chicago’s employment base in that sector exceeds the national average.) Especially during the 1990s, the metropolitan area experienced very rapid growth in these industry sectors. This expansion was thought to have been accompanied by geographic changes. In particular, while Chicago’s services industries had historically grown and developed through its local trade linkages with Midwest goods producers, business and financial services were now thought to have strengthened and lengthened their ties with international and U.S. cities and regions. If this were actually the case, the traditional patterns in which Midwest manufacturing production declines are strongly transmitted through Chicago’s services industries would have weakened.

3. Index of concentration – Chicago MSA vs. U.S. (September)

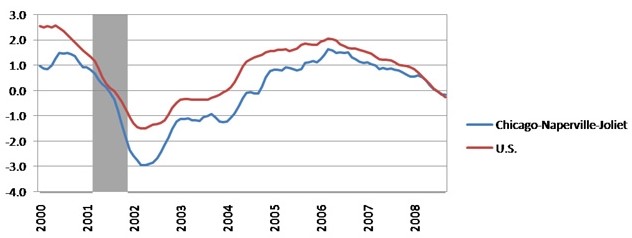

To the contrary, the subsequent experiences of the recessionary period of 2001 and its aftermath tend to suggest that Chicago’s restructuring into business and financial services has not buffered it from national business downturns. As measured by total payroll jobs, the Chicago area’s decline of 3 percent in 2001 was at twice the pace of the national average (see chart below). And if the professional and technical services sector has become Chicago’s new bellwether, its performance during the past downturn is not encouraging. From a year-over-year growth peak of 7 percent in 1999, Chicago jobs in the professional and technical sector fell by over 8 percent during 2002. Though we may not think of these services as being sensitive to the general level of business activity, their responsiveness to business swings is much like producers of investment goods and capital equipment. That is, firms tend to expand their purchases of professional services such as advertising, marketing, business meeting travel/convention, and management consulting when they are expanding their markets and investing, but they tend to retrench their purchases of such services when they are retreating.

4. Total nonfarm employment – Chicago MSA vs. U.S. (3-month moving average percent change year over year)

More generally, although Chicago has broadened and diversified its economy, many of its hallmark sectors remain sensitive to swings in the overall economy. According to the chart above, Chicago remains concentrated in manufacturing. So, too, Chicago remains a goods transport and distribution hub for manufactured goods that are both domestically produced and internationally traded. While many of the area’s services such as education and health are somewhat impervious to general slowdowns, many of its business services are volatile, depending on the fortunes of Midwest goods-producing sectors and, increasingly, on the prosperity of national and international customers.

Chicago also maintains high job concentration in financial and insurance sectors. Unlike the job bases of the New York and Los Angeles metropolitan areas, Chicago’s job base is not greatly exposed to the most adversely affected subsectors of financial services—namely, investment banking, securities dealers, and mortgage finance companies. That said, the remaining financial services subsectors are not expected to be sources of net job growth in the months ahead.

Note: Thanks to Emily Engel for assistance.