Supply-side efforts at building skilled workforce

Wage growth continues to grow more sharply for educated workers, but how can states and cities build their work force in this direction?

For one, a “grow your own” approach to enhancing the local supply of educated workers may be helpful. States tend to have some advantage in retaining individuals who grew up and went to college within the state. A study found that 54% of students that were both residents of the state and attended college in-state were working in the state 15 years later. The number falls to 35% if the student residents attended college in another state. The percentage drops to 11% for non-residents who attended college in the state. A recent policy report for the Milwaukee area suggests that a potential way for states to make use of this home state advantage would be to increase their high school graduation rate and better prepare their students for college. Even if these students do not attend college, the policy report notes that a rise in the high school graduation rate would raise average incomes and would help fill jobs being left open by retiring baby boomers. Nonetheless, states and cities will see the greatest returns to education if these high school graduates do obtain a college education and either stay in-state or return home after college.

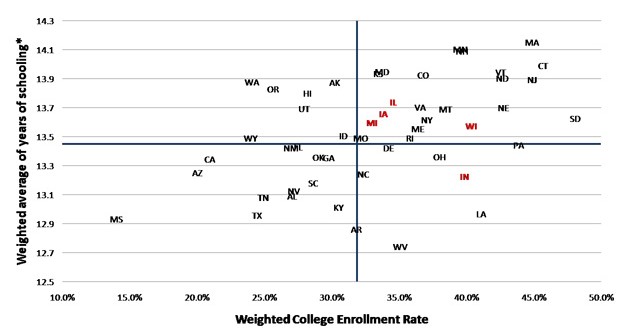

How are states doing in “grow your own” initiatives? The chart below plots state college enrollment versus educational attainment of the workforce. The state’s college enrollment rate is weighted by the state’s average high school freshman graduation rate, which reflects a state’s tendency to graduate its high school students. Therefore, the x-axis number is the interaction between the percentage of high school graduates that go to college and the percentage of students that completed all four years of high school. On the vertical axis, we measure educational attainment of the state’s workforce as the weighted average of years of schooling per worker. The horizontal and vertical lines in the graph (in blue) are the U.S. averages.

Figure 1. 2004 weighted college enrollment rate vs. educational attainment

Note: Rate weighted by average high school freshmen high school graduation rate by state.

The states positioned in the top right quadrant of the chart have an above average educational attainment per worker and are sending a higher proportion of students to college than the U.S. average. Four of the five Seventh District states (Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin) reside in this quadrant. Although Indiana (bottom right quadrant) has lower than average years of schooling, the state seems successful in preparing and sending its students to college as seen from its above average enrollment rate. It appears as though the District states, which tend to be high-income states, have been successful in educating their own and sending them to college. There is some slippage in this measurement since a large and variable share of those who enroll in college go on to complete their degree.

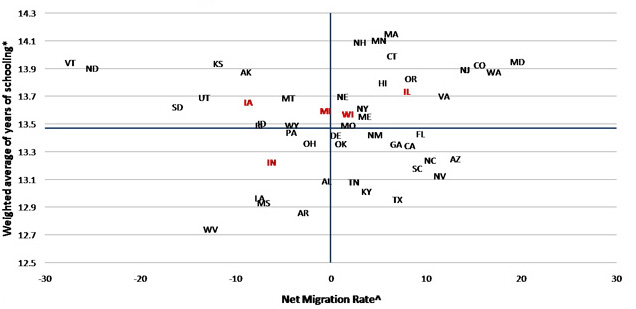

Educating a state’s own individuals does not guarantee the young professionals’ retention or return to the state after college. Therefore, states should also focus on the migration of these young professionals into and out of their state, especially as the young, college-educated professional cohort is the most mobile of any cohort in the U.S. A special Census Report calculated that 75% of young and single and 72% of young and married college-educated professionals between the ages of 25 and 39 relocated between 1995 and 2000. Therefore, a part of a state’s future economic success is tied to attracting these young professionals from other states. In the next chart, states are plotted based on their 3 year average net migration rate of young professionals versus the state’s weighted average years of schooling. For the Seventh District, Illinois and Wisconsin (top right quadrant) have average years of schooling above that of the U.S. average and are importers of young educated professionals as seen through their positive net migration rates. Iowa, Michigan, (top left quadrant) and Indiana (bottom left) have negative net migration rates. These states seem to be exporters of young college-educated professionals.

Figure 2. Average net migration rate of 22-29 year olds with at least a Bachelor's degree vs. educational attainment

^ Average of 2004, 2005, and 2006 net flows of 22-29 year olds with at least a bachelor's degree per 1,000 total 22-29 year old state residents.

For the two charts above, the educational attainment of the existing work force was put on the vertical axis for two reasons. The educational attainment level reflects the past success of the state’s educational system in producing an educated work force. In addition, educational attainment will vary with the industry mix of the state economies since industries tend to have varying workforce skill demands. In turn, a state’s industry mix is determined by a host of historical developments in the state’s development process. Indiana, for example, ranks among the top 3 states in manufacturing concentration, a sector which historically has not required a post-secondary education (though this is changing to some degree).

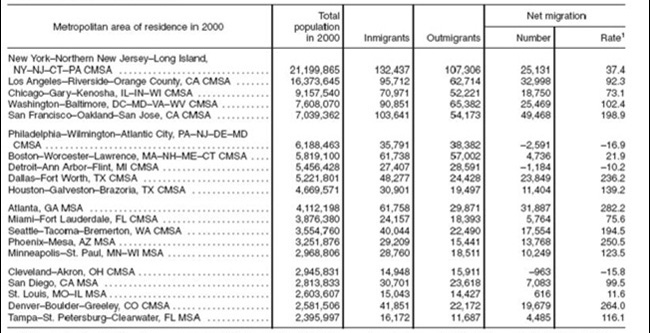

As states compete for these young professionals, they may need to offer unique opportunities to set themselves apart. From an economic development standpoint, cities can be an integral part of a state’s effort to increase their level of human capital since cities can be the gravitational force that brings young professionals to the state. Based on the table below, 17 of the 20 largest metropolitan areas had a positive in-migration of young well-educated professionals between 1995 and 2000, including two Seventh District metropolitan areas: Chicago and Minneapolis-St. Paul. Cities have the ability to attract young well-educated residents because they still offer powerful benefits to their inhabitants.Cities eliminate the distance between people and ideas by allowing ideas to be shared in both formal and informal settings, thereby increasing the opportunities for innovation. As such, cities have become centers of learning for young college-educated professionals just starting their careers. As studied by Ed Glaeser, professionals come to cities to take advantage of the knowledge externalities provided by interactions with other well-educated and successful individuals to enhance their own productivity. Glaeser found that workers tend to learn faster in cities and enjoy higher wage growth. The density of educated individuals living in a city creates informational spillovers, thick labor markets, and division of labor leading to specialization. Cities also reap the benefits of these individuals through their overall increased productivity and innovation.

Table 1. Net domestic migration rates for 20 largest metropolitan areas for the young, single and college educated: 1995 to 2000

Notes: Data based on a sample. For information on confidentiality protection, sampling error, nonsampling error, and definitions, see the summary file.

A negative value for net migration or the net migration rate is indicative of net outmigration, meaning that more migrants left an area then entered it.

The young are those who were aged 25 to 39 in 2000; the single are those who were never married, or were widowed or divorced in 2000; and the college educated are those who had at least a bachelor's degree in 2000.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Since cities can play an important role in regional economic development, the Milwaukee area policy report suggests a combination of two ways for cities to enhance their efforts to increase their pool of human capital through migration. First, the city should try to enhance the available job opportunities to young professionals that match their career and personal goals, as these individuals want to learn, network, and develop professionally. The report recommends that local businesses and civic organizations join forces to share resources and ideas to spur innovation and growth to create or improve jobs. Secondly, the American city has been transforming into a cultural and entertainment center. Young, college-educated professionals place special emphasis on amenities offered by a city. They expect high-quality and unique recreational opportunities such as restaurants, sporting events, live music, and nightlife venues. Therefore, cities might need to augment or diversify their recreational offerings to retain and attract these young professionals and provide a vibrant and livable city.

These days, states and cities must select from a wide and complex array of economic growth and development policies to find the strategies that are most appropriate for their situation and circumstances. Increasingly, they are favoring policies related to skilled work force availability.