The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

In the second quarter of 1987, Eastman Kodak had $529 million of commercial paper outstanding to fund its day-today operations. Five or ten years ago, Kodak would have turned to one of the dozen or so money center banks for this sort of funding. Such a change in Kodak’s financing patterns is part of a broader trend in the nation’s financial markets.

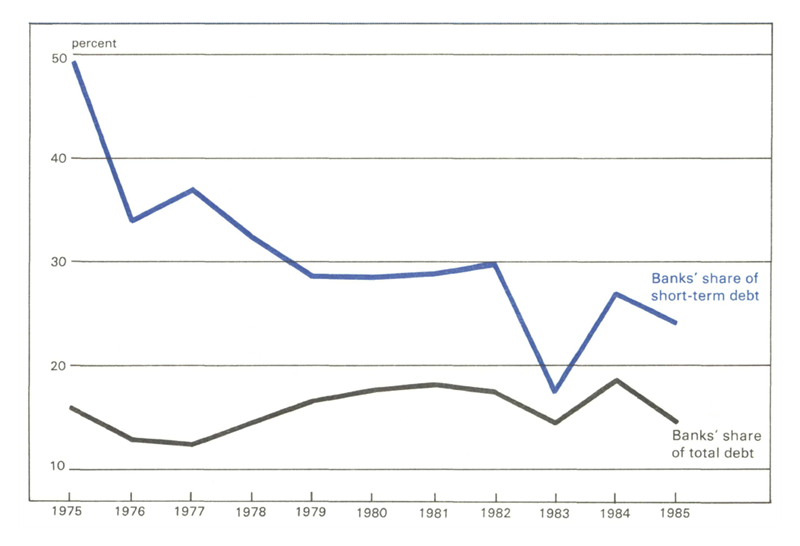

An increasing number of nonfinancial firms have discovered that raising funds in the commercial paper market is cheaper than borrowing funds from a bank. Indeed, between 1975 and 1986, banking’s share of short-term borrowings by large manufacturing firms fell from 48 percent to 27 percent. Most of this loss in market share can be attributed to the growing importance of commercial paper. Since 1981, banking’s share of total borrowings by these corporations has also been under pressure.1

1. Lending to big manufacturing firms: Banks’ share is down

These declines in market share have put substantial earnings pressure on money center banks that had traditionally been major suppliers of credit to the big, established firms. It may also have increased bank risk since these corporations—particularly those that issue commercial paper-are among the nation’s most creditworthy borrowers. This market change has pushed banks to reduce the costs of providing credit services by finding new ways to deliver the service. As a result, many in the banking industry have begun to question the usefulness of continuing to operate under a banking charter.

Bank competitiveness in commercial lending

With the decline in banks’ market share, banks are shifting their customer base and increasing their reliance on off-balance-sheet activities. Data published by the Federal Trade Commission indicate that banks have become more important as suppliers of funds to smaller, possibly more risky, corporations. In 1975, banks provided 37 percent of funds borrowed by manufacturing firms with assets under a billion dollars. By 1986, banks provided over 50 percent of the funds borrowed by these firms.

Banks have also rapidly increased their issuance of off-balance-sheet guarantees and are currently attempting to create a secondary market for commercial loans. Off-balance-sheet guarantees enable nonbanks to fund loans while banks continue to bear, for a fee, all or part of the risk. The most important of these guarantees are formal loan commitments and standby letters of credit.

Standby letters of credit are often used to guarantee performance of debt contracts. While no hard data are available, it would appear that standbys provided backing for at least 0.2 percent of the debt of nonfinancial corporations in 1980 and at least l.8 percent of their debt in 1985. Loan commitments perform a similar function, frequently providing liquidity backup for commercial paper issues. One form, lines of credit under formal commitment, has grown from 8.5 percent of debt at nonfinancial corporations in 1975 to 16 percent in 1985.

The costs of regulation

No question about it—banking has changed in the last ten years. Banks have become less important as suppliers of low-risk short-term credits to large corporations and more important as suppliers of funds to smaller, often more risky, corporations; off-balance-sheet guarantees have grown rapidly; and banks are developing a secondary market for commercial loans to investment grade borrowers.

These developments should not be viewed as simply another phase in the inevitable evolution of financial markets. They are also the result of regulation that gives banks a comparative advantage in originating certain loans and in bearing credit risk, but disadvantages in funding them. These disadvantages stem from the costs of federal deposit insurance premiums, foregone interest on required reserves, and mandatory equity capital requirements that exceed those that banks would maintain in the absence of regulation and deposit insurance. These can be considered—and are often termed—“regulatory taxes.”

Against these costs, banks must balance the benefits of a bank charter—federal deposit insurance and access to the discount window. These two advantages, especially deposit insurance, allow a bank to attract deposits at a lower interest rate than would otherwise be possible given the risks that it is taking. However, for low-risk loans, this lower rate may not be low enough to compensate the bank for the regulatory costs.

When banks have a disadvantage in funding low-risk borrowers, both banks and borrowers have strong incentives to avoid the regulatory cost. Commercial paper issuance, loan sales, and guarantee activities are all ways to avoid the regulatory burdens associated with the funding of loans by banks. Off-balance-sheet guarantees permit the banks to continue bearing a customer’s credit risk while avoiding the burden of reserve requirements and deposit insurance premiums. They may have also permitted banks to take additional risk without being forced by regulators to hold additional equity capital.

Reserve requirements were eased…

Until recently, reserve requirements were the most important factor affecting bank competitiveness. Reserve requirements raise bank funding costs by forcing banks to hold noninterest-bearing balances with the Federal Reserve System.

To see the costs of reserve requirements, suppose that Kodak could have borrowed $20 million on the commercial paper market at an interest rate of 8 percent. In order for a bank to lend Kodak the same $20 million, it would have to take in additional deposits. This increase in deposits would cause its required reserves to rise. If all the additional funds were obtained by issuing certificates of deposits to corporations, the bank would face a reserve requirement of 3 percent, and would have to raise $20.6 million. Of this, $20 million would be lent to Kodak and $0.6 million would be deposited at the Fed in a noninterest bearing account. In order for the bank to pay depositors an interest rate of 8 percent, it would have to charge Kodak at least 8.25 percent. Clearly, the bank’s depositors and Kodak would both be better off if the bank could find a way to avoid the reserve requirement.

Reserve requirements played an important role in stimulating the growth of commercial paper during the 1970s. During that period, banks sought to escape the competitive disadvantage by leaving the Federal Reserve System. Congress responded to the “membership” problem by passing the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA), which drastically lowered reserve requirements.

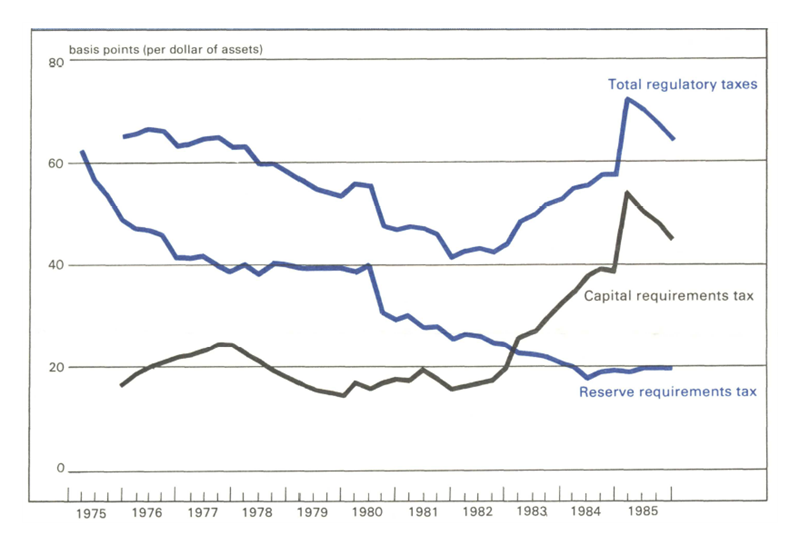

Both as a result of changing funding practices and DIDMCA-mandated reductions in reserve requirements, the funding disadvantage created by reserve requirements has declined in importance. Between 1976 and 1986, reserve requirements at a large bank declined from 4.5 percent of domestic assets to 1.8 percent of deposits. Assuming an interest rate of 10 percent, the “reserve requirement tax” would have fallen from 0.45 percentage points (45 basis points) in 1976 to 0.18 percentage points (18 basis points) in 1985.

With the reduction in reserve requirements, many expected that banks would find themselves in a stronger position relative to nonbank firms. Instead, we have witnessed a continued growth in commercial paper, tremendous growth in off-balance-sheet guarantee activities, and since 1981, a sharp decline in banks’ importance as a source of funding for the nation’s largest corporations. One possible explanation is that increasing equity capital requirements have offset the impact of declining reserve requirements.

…but capital ratios were hiked

The 1970s saw a steady decline in the ratio of equity capital to total assets at money center banks. By the late 1970s, regulators were becoming concerned that the nation’s banks were going to need additional equity capital in order adequately to deal with an economy that was becoming increasingly volatile. Subsequent events—the energy and agricultural crises, and problems with third world debt—have demonstrated that this regulatory concern was legitimate.

In 1981, federal banking agencies moved to establish minimum capital standards. Initially, the minimum was set at 6 percent for community banks and bank holding companies, and 5 percent for regional banking organizations. In June of 1983, the minimum primary capital ratio for regional organizations was extended to the multinational organizations. In 1985, the minimum primary capital ratio for regional and multinational organizations was increased from 5.0 to 5.5 percent. In early 1986, the Federal Reserve proposed alternative minimum capital requirements designed to control for the wide differences in the level of off-balance-sheet activity.

While the increase in minimum capital requirements has led to a better capitalized banking system, it may also have had unintended effects on the ability of banks to make low-risk loans. Capital requirements place banks at a competitive disadvantage if income on equity is taxed more heavily than income on debt and if regulators require banks to hold more equity capital for a given portfolio than banks would choose to hold in the absence of regulation and deposit insurance.

Equity is clearly taxed more heavily than debt. However, the difference in tax treatment can be difficult to determine because the effective tax rate paid by banks is strongly influenced by changes in their ability to shelter income with tax-exempt securities.2

The current minimum primary capital ratio of 5.5 percent may also be too high for some types of loans. Money market funds choose to offer deposits redeemable on demand backed by commercial paper, bank certificates of deposit, and treasury securities, suggesting that in the absence of regulation the optimal level of capital for this type of activity is quite low.

Because regulators raised capital requirements, the ratio of market value of equity to assets at banking organizations with over $10 billion in assets has increased from about 2.5 percent in 1978 to about 5.5 percent in 1986—an increase of 120 percent. This increase in equity, which is more heavily taxed, has caused total funding costs for banks to rise. This effect has been reinforced by changes in the tax code, which have reduced the ability of banks to shelter income by holding tax exempt securities in their portfolios.3

The regulatory tax on low-risk domestic assets is the sum of the reserve requirement “tax” and the burden of the equity capital requirement. Assuming a constant 10 percent interest rate, the total regulatory tax on holdings of low-risk domestic assets fell sharply between 1977 and 1981 (see figure 2). This decline was largely a result of changes in bank balance sheets. Reserve requirements continued to decline after 1981, largely as a result of DIDMCA. However, the burden of capital requirements rose sharply. As a result, total regulatory taxes began to rise. By 1985, the total regulatory tax was either the same or slightly higher than it was in 1977, depending on the measure of capital used. In 1977, capital requirements accounted for just over 30 percent of the regulatory burden on low-risk assets. By 1985, they accounted for over 80 percent of the cost.

2. The burden of regulation*

In 1976, a low-risk borrower would have been able to reduce its total interest bill by 6.5 percent if it had obtained its short-term funding from the commercial paper market rather than the banking system. By 1982, the cost savings had fallen to 4 percent. However, by 1985 it had risen to 6.7 percent. Clearly, such borrowers still have strong incentives to obtain funding from the commercial paper market.

Changes in regulatory costs have led to changes in bank market shares. Figure 3 plots banks’ share of total debt of large manufacturing corporations and total regulatory taxes. Total regulatory taxes declined steadily from 1977 to 1982. They began rising in 1983. Banks’ share of total debt at large manufacturing firms rose steadily from 1977 to 1981. Beginning in 1982, banks’ share of debt began to fall as regulatory taxes began to rise.4

3. Regulatory taxes and banks’ share of big business lending*

Conclusions

The increase in bank capitalization that took place during the 1980s was clearly necessary, in terms of bank safety. However, the application of a single capital ratio for all types of assets has had an inadvertent impact on bank competitiveness in the market for low-risk loans. The increase in equity capital mandated by regulators appears to have completely offset the gains in bank competitiveness achieved as a result of lowering reserve requirements. As a result, low-risk borrowers still have strong incentives to discover alternatives to conventional bank financing. This search for cheaper funding sources has subjected money center banks to significant earnings pressure.

Expanded powers for bank holding companies are often proposed as the solution to the competitiveness problem. But these proposals will only make companies that own banks more profitable. It is unlikely that banks themselves will become more profitable or more competitive in the market for low-risk assets. An alternative solution would be to reduce the banks’ disadvantage in funding low-risk loans.

One way that regulatory taxes could be reduced without sacrificing bank safety and soundness would be to permit banks to substitute subordinated debt for equity capital. This would permit regulators to increase the capital buffer in the banking system without reducing the banking system’s ability to compete in the low-risk loan market. Another solution would be to distinguish between high- and low-risk commercial loans in computing a bank’s minimum capital ratio. In either case, the result would be a more effective capital market in which bank competitiveness would be determined more by efficiency than by regulation.

Notes

1 Data on bank lending to small and large manufacturing firms were obtained from the Quarterly Financial Reports published by the Federal Trade Commission. Large firms are defined as firms with over a billion dollars in assets.

2 For a discussion of bank taxation see Matthew Gelfand and Gerald Hanweck, “The Effects of Tax Reform on Banks,” The Bankers Magazine, (January/February 1986).

3 A detailed discussion of the procedure used to calculate the tax disadvantage of equity is available from the author on request.

4 The decline in market share that began in 1982 was interrupted in 1984 by a sharp upward spike. The cause of the spike is unclear, however it may have been the result of dramatic changes in the growth of total borrowings between 1983 and 1984. During 1983, total borrowings by these firms actually declined by 7 percent. In 1984 total borrowing increased by 17 percent. This change in growth rates is two and a half times larger than any other observed in the sample. Bank borrowing may have simply acted as a shock absorber, declining more rapidly than total borrowing in 1983 and expanding more rapidly than total borrowing in 1984. If this explanation is correct, then it would appear that increases in regulatory taxes do lead to decreases in banks’ share of borrowing by large manufacturing corporations.