The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Optimism regarding the banking industry has been in short supply in recent years. This is not surprising, given the apparent abundance of bad news and the relative scarcity of good tidings. Last year, in particular, was a tumultuous finale to an eventful and turbulent decade for the industry.

Most are all too familiar with the recent troubles in the banking industry. Banks with heavy concentrations in commercial real estate loans have suffered large losses. In addition, the loan portfolios of many banks have exhibited other signs of weakness. Banks have responded to deteriorating loan portfolios by increasing provisions and charge-offs, deepening the pressure on earnings. These problems have contributed to many bank failures, adding to the liquidity problems of the bank deposit insurance fund.

Despite the recent turmoil in the banking industry, however, there is cause for optimism. The condition of the industry is difficult, but manageable. Asset quality is stabilizing, and banks have built up their loan loss reserves to a level that provides much better coverage for problem loans. The improving economy should facilitate further improvement. Although the economic recovery is likely to be more modest than in the past, it will occur and banks will benefit. Another hopeful sign is the U.S. Treasury’s proposal for banking reform. If enacted, the main elements of the proposal would provide a long-expected and much-needed legislative response to some of the fundamental problems facing the industry.

There are still a number of significant concerns. Resolving the critical issue of deposit insurance reform is particularly important. But the major elements are in place for an exciting and rewarding future for the banking industry.

Cause for optimism

At this point, most of the banking industry’s troublesome asset problems have been identified. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that the quality of loan portfolios will stabilize and, over time, show signs of improvement. While there could be more unfavorable developments in commercial real estate in some regions, these problems should be manageable. Most banks appear to have sufficient capital to weather the storm.

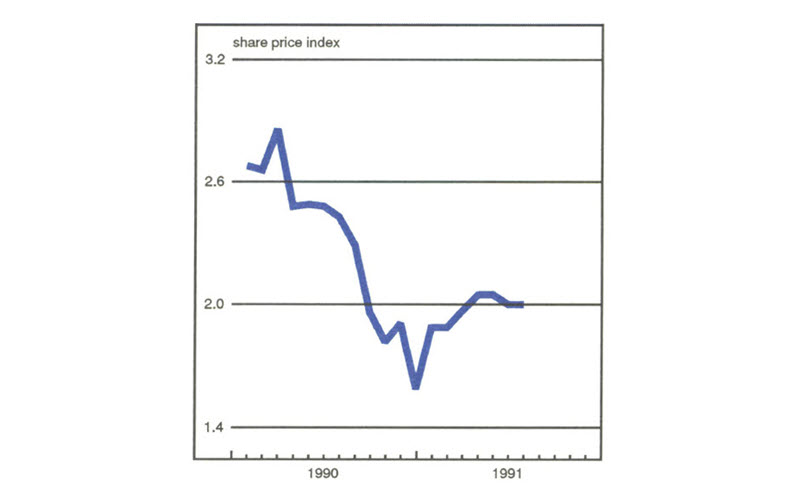

The resumption of property sales is an encouraging sign. There is a growing belief that some of the current deeply discounted prices represent a bottoming in the collapse of real estate values (see figure 1). These transaction prices are well below earlier levels, but the fact that sales are occurring makes it possible for lenders to begin to evaluate projects. The commercial real estate components of banks’ loan portfolios are emerging from a free-fall phase during which it was all but impossible to determine the collateral value of many real estate projects because there was not a price or value basis for establishing reasonable property values. The financial markets seem to share this sense of increased optimism. After a decline of some 40% during 1990, share prices of real estate investment trusts are only 25% below their January 1990 levels. It is far too early to forecast even a modest rebound in commercial construction, but once the necessary adjustment process is completed, new building will not be far behind.

1. Real estate bottoms out

Back to basics

A second reason for optimism is the tightening of credit standards and pricing, a trend that should stabilize credit quality and profitability. After years of slippage during which credit standards were significantly weakened, banks are undergoing a self-correcting process. Federal banking supervisors have played a role in this process—lending officers are quite aware that examiners are looking over their shoulders. Consequently, there has been a heavy supervisory focus on some specific categories of lending, especially highly leveraged transactions.

This self-correcting process has resulted in a restraint on bank credit extension, popularly referred to as the “credit crunch.” The word “crunch,” however, is incorrect. A crunch occurs when creditworthy borrowers who would normally find it possible to obtain a loan, even under adverse economic circumstances, cannot obtain financing. A crunch is most likely to occur when all lenders serving a particular class of customers find their lending capacity contracting. We have experienced this type of credit shutdown in the past. This, however, has not been the case in recent months, particularly in the Midwest.

While the regulatory process has played a role in this credit restraint, it has not been the principal cause. Rather, the driving force has been the market. That is, the industry is reacting to adverse developments, which is exactly how the process should work. Moreover, borrowers are rethinking their attitudes about the desirability of excess leverage. Both lenders and borrowers are returning to the basics.

Profitability should improve

Bank profitability is likely to improve, although it has not yet shown up in the numbers. While competitive pressures remain intense, spreads are widening. Surveys conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago during the last 12 months, for example, suggest that spreads on loans to high-quality corporate customers have gone up by 30 basis points since the third quarter of 1990. As asset quality stabilizes, the need for continuing high levels of loan loss provisions will diminish. This, in turn, will result in a rebound in earnings. In addition, competitive pressures from some international banks that forced spreads to very narrow margins have eased. The adoption of risk-based capital standards by the major industrial countries has played a role in this process. As uniform and consistent standards have become effective, the competitive inequality that stemmed from differences in national capital requirements has been reduced. The adoption of the risk-based standards has increased pressure for higher earnings and capital on an international basis, providing U.S. institutions with an improved opportunity for profit.

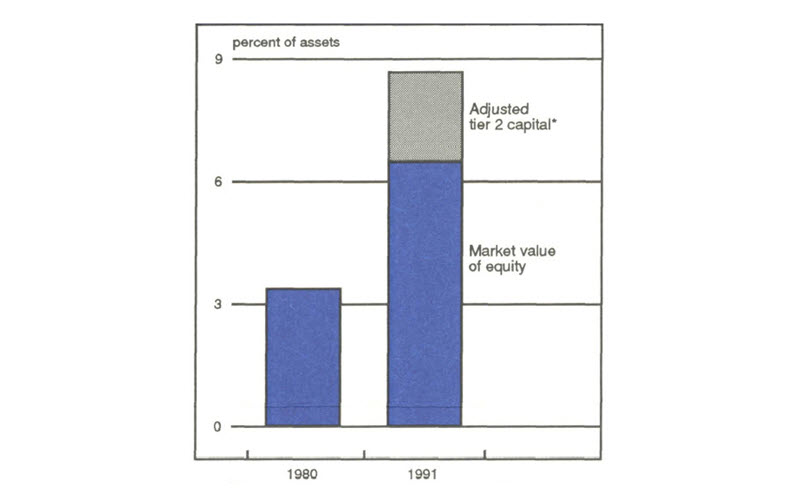

The improvement in the capital position of U.S. banks is a crucial element for future prosperity. Regulators have strongly encouraged the nation’s largest banking organizations to improve their capitalization, a campaign that clearly has produced results. The nation’s largest banks have increased their equity positions, measured on both accounting and market capitalization bases (see figure 2). In addition, most banks have the added protection of a layer of supplementary capital elements, such as subordinated debt and perpetual preferred stock. Just a decade ago, the amount of these supplementary capital elements was negligible. Adding core capital—consisting primarily of common shareholders’ equity—to these supplementary elements reveals an encouraging trend: the real capital positions of large U.S. banks have more than doubled in the last ten years. As a result, for the first time in many years there are a number of U.S. banks—both regional and money centers—with market capitalization ratios as high as the traditionally well-capitalized Swiss, German, and Japanese banks.

2. Real capital of large banks

Sources: Standard & Poors and Salomon Brothers.

Well-capitalized banks have a clear and important advantage in this increasingly competitive environment. This factor bodes well for midwestern banks, whose capital positions compare very favorably with the rest of the nation, and for smaller banks, which have maintained their traditionally high levels of capital.

Benefits of deregulation

The operating environment for the industry should be more favorable as a result of the deregulation of the 1980s, which is producing the expected benefits. Some of the bankers who have experienced the tumult of the past decade might debate the desirability of this process. It is useful to remember, however, the experience of other industries that have been deregulated; it has not been an easy road for brokerage, trucking, airline, and the other industries that have gone through this transition. There was no reason to expect that the transition for banking would, or should, be any different, and it has not been. Given the deep public interests included in banking, as well as the potential taxpayer exposure, the concerns are clearly different, but the adjustment process is not.

Despite the difficult adjustment, deregulation has clearly yielded benefits. Much of the regulatory structure that impeded the business has been removed. Institutions operating in this more open environment have been able to achieve a high level of operating efficiency. Most important, however, is the significant public benefit resulting from this process: Both retail and wholesale customers have had access to a wider array of services at very competitive prices.

In response to increased competition the industry has been consolidating—the number of banking organizations declined by more than 20% during the 1980s. Interstate consolidation is not only reducing overall operating expenses and pushing costs down, it is increasing capital positions and creating more diversified institutions. As this process continues, future regional downturns, like those that occurred in the Southwest and Northeast, will pose less of a threat to the health of the U.S. banking system.

Continued consolidation, however, will not mean the demise of the smaller- and medium-sized institution. These banks will have many opportunities to thrive and profit in their own markets. Those community banks that know their markets and their customers very well, and can be particularly responsive to local needs, will prosper. Nevertheless, competition will intensify for all banks, large and small. Efficiency will be all-important.

The need for deposit insurance reform

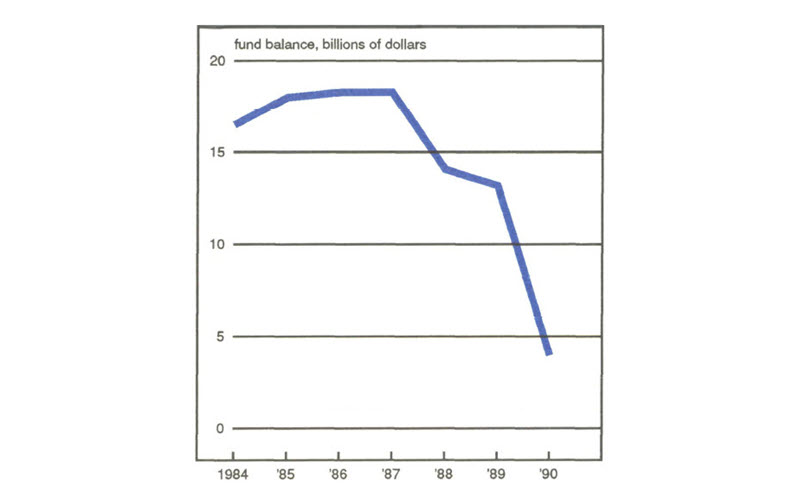

There is cause for optimism, but the gains of the past decade, as well as the prospects for the future, will be threatened if we fail to reform our system of deposit insurance. Since 1987, the FDIC reserves have declined from a high of $18 billion to a current official estimate of approximately $4.5 billion; some estimates place the fund balance at a much lower level (see figure 3).

3. BIF shrinking reserves

There is a compelling need for recapitalization and reform. No system of dealing with problem institutions can be fail safe; the insurance fund will occasionally face losses, that is its basic purpose. Clearly, however, the sheer magnitude of some of the individual claims and the rapid depletion of the bank insurance fund in the last three years are indicative of deeper structural problems with our insurance system. Developing means of addressing problems before situations deteriorate and lead to large claims against the insurance fund is fundamental to any solution.

The concept of progressive supervisory intervention and prompt corrective action in the Treasury’s reform proposal is an important step toward achieving this goal. The ultimate risk to the bank insurance fund will be significantly reduced by adopting a known, understood, and acknowledged system under which regulators will take progressively specific steps to deal with deteriorating capital positions. Some might argue that emphasizing capital avoids the narrower issue of deposit insurance reform. In my view, the emphasis on capital is absolutely appropriate and will ultimately reduce claims against the insurance fund. Indeed, the success of a problem bank in raising new capital is the principal factor determining whether or not it will fail. Problem banks that are unable to raise new capital fail the ultimate market test and should be presumed to be insolvent. Progressive supervision would also be an important step toward ensuring that institutions considered “too big to fail” will not burden the U.S. taxpayer or the banking industry since banks would be more likely to be recapitalized before they become insolvent.

There are any number of specific examples in which a regulator’s insistence on increased capital levels has made the difference between failure and success. Establishing specified levels of capital would provide benchmarks against which regulators would take appropriate action. A regulator would take increasingly severe supervisory action as an entity’s capital deteriorated and it moved down in the zones. All parties would understand that a line list of specific actions would be triggered when an institution falls into an unsatisfactory zone. If corrective action by the institution fails to restore an adequate level of capital, the bank would be forced to merge or close. Importantly, this action would occur before actual insolvency.

Once the concept has been established, the exact capital levels associated with each zone can be determined through consultation and negotiation. The adoption of the risk-based capital standards for banks is an example of this consultative process.

Certainly, there are a number of issues to be considered as a result of this major change in procedure. The extent of supervisory involvement with some institutions will undoubtedly increase. But only the weaker institutions would be affected. For stronger banks, quite the opposite would occur. For example, for some activities, stronger banks may be able to simply notify regulators, rather than having to file an application.

There is also the concern that early closure will result in the loss of private assets of stockholders and creditors. Shareholders, however, would have a claim on any surplus arising from the sale of a bank or its assets. As we have seen from recent experience, the ultimate cost to the insurance fund of deferring action is much greater. In the long run, prompt closure will minimize costs.

There is also the difficult issue of whether the appropriate supervisory response should be absolutely specific and mandatory for each zone. While a mandatory response has appeal to some, a strong argument can be made for the exercise of supervisory judgment, particularly at the outset of this new procedure. This exercise of judgment would put far more pressure on the supervisors; nevertheless, supervisors will need the latitude to use discretion in the event of mitigating circumstances.

It is important to realize that the adoption of the Treasury’s proposals for progressive supervisory intervention and prompt corrective action will not completely resolve the thorny issue of “too big to fail” nor will it do much to restore creditor discipline.

The continued invocation of the “too big to fail” doctrine will have serious equity and competitive implications for the banking industry. Healthy banks—big and small—ought to be particularly concerned. However, there is no need to accept the status quo. Regulators need to work with the industry to identify institutional practices that make the financial system prone to systemic risk. Some progress has been made, most recently in the area of electronic payments, but more is needed.

To complete the reform of the deposit insurance system, some form of creditor discipline will also need to be reintroduced. In today’s system, creditor discipline is supposed to be supplied by uninsured depositors. However, policymakers have been so concerned about deposit runs that they have been unwilling to permit uninsured depositors to suffer losses. Given these concerns, it would seem more appropriate to rely on other creditors—particularly subordinated debtholders—to restore market discipline. Forcing banks to maintain a cushion of subordinated debt will create additional pressure to avoid excessive risk-taking and create private sector claimants that have an active interest in seeking the closure of insolvent banks.1

Deposit insurance reform is a particularly important issue for midwestern banks. It is a time-honored maxim that survivors pay. Certainly, this is the case under our system of deposit insurance. Midwestern banks are among the most consistently profitable in the country, and industry conditions in the region are comparatively favorable. Therefore, institutions in the Midwest are likely to be among the survivors that will have to pick up the check.

Picking up the deposit insurance check will have competitive implications for those institutions that are survivors. The only responsible way to reduce these costs is through reform of the regulatory system. If these reforms are not forthcoming and the costs of deposit insurance are not reduced, the profitability of domestic banks will suffer, and foreign banks and nonbank competitors will be able to make further inroads in the customer base of U.S. banks. Once U.S. banks have lost these customers, they may find it difficult to attract them back.

Conclusion

Thus far, the banking system has been able to cope with some major problems—more than many would have imagined a decade or two ago. This difficult period has laid a foundation for improved profitability. As the economy improves, so will the operating environment for banks. Asset quality problems will continue to moderate for the industry as a whole. And as earnings increase, banks should further improve their capital positions. However, if legislators and regulators fail to address the need for deregulation and deposit insurance reform, the industry’s future prospects will be called into question.

Fortunately, it is entirely possible that Congress will enact reform legislation that will accelerate the deregulation process, increase opportunities for banks, and reduce the cost of deposit insurance. For these reasons, it is possible to be optimistic about the future.

Note

1 An in-depth discussion of these issues can be found in the July 1990 and May 1991 issues of the Chicago Fed Letter.