The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Anyone who follows the news, even casually, or reads product labels, is aware that the world economy has become more interdependent in recent decades. Indeed, the worldwide integration of national economies—through goods and services trade, capital flows, and operational linkages among firms—has never before been as broad or as deep.1

Nevertheless, the course of globalization has not always been smooth. At the start of the 20th century, the global economy was highly integrated. In some regards, it was nearly as integrated as it is today. Yet two decades later, a noteworthy commentator lamented the apparent end of this economic integration. John Maynard Keynes wrote an eloquent and oft-cited description of the pre-World War I economy:2

What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was which came to an end in August, 1914! ... life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth ... he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world ... But, most important of all, he regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement, and any deviation from it as aberrant, scandalous, and avoidable.

In the decades that followed, two world wars, the Great Depression, and protectionist policies seemed to bring economic integration to an end. Since then, however, advances in technology and changes in policy have worked to reopen borders. Despite Keynes’ characterization of the pre-World War I period as an “extraordinary episode,” the economic globalization and buoyancy of that period was not an aberration. Rather, it was the 1913–50 period that stands out for its uncharacteristically weak growth in both output and trade. After 1950, the world economy resumed its trend toward globalization. But it took time to make up the ground lost: In the U.S. and elsewhere, the level of trade relative to output has consistently exceeded early 20th century levels only in the past few decades. Indeed, just a few years ago, academic papers debated whether the world economy in the 1980s and early 1990s was more, or less, integrated than it was in 1900.3

This Chicago Fed Letter reviews the ebbs and flows of globalization during the past century and argues that a continuing commitment to open markets is worth pursuing as a way to raise living standards both at home and abroad.

Growing importance of trade and capital flows in the U.S.

Trade and, to a much lesser extent, investment links were well established a century or more ago, but both deteriorated during the interwar period. Today, global economic ties have rebounded and are generally more extensive and intensive than ever before.

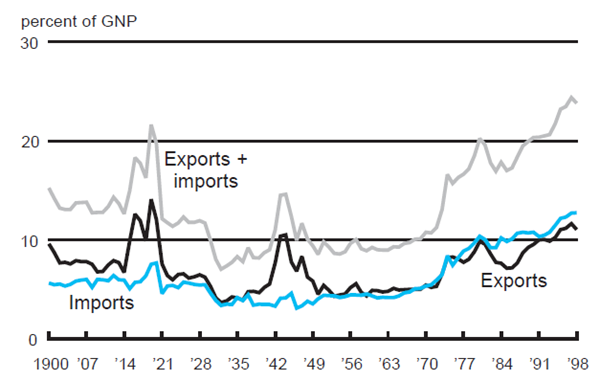

Figure 1 illustrates the historical ebb and flow of U.S. trade. Except briefly around the time of each world war, the ratio of trade (exports plus imports) to gross national product (GNP) did not return to turn-of-the-century levels until the 1970s. Recently, however, this ratio has approached 25%, its highest point in at least a century.

1. U.S. trade relative to GNP since 1900

During much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. participated actively in a generally vibrant world trade.4 Internationally, there were few nontariff trade barriers. The interwar period that followed, however, was largely one of rising tariff and nontariff barriers—in the U.S. and elsewhere—and global disintegration rather than integration. Since World War II, technological developments and the gradual liberalization of international trade and capital flows have put integration on the upswing.

Some of this rising trade can be attributed to “two-way” intra-industry trade. Anecdotal evidence and recent studies document how production processes have been increasingly divided up and reallocated, either domestically or globally.5 Tasks, such as research and development, design, assembly, and packaging, are performed by firms in the U.S. and elsewhere, based on countries’ relative strengths in completing them. Consider the computer industry. According to a recent report, in 1998 an estimated 43% of domestic producers’ total shipments was exported, and an estimated 58% of final and intermediate domestic consumption was imported; some 60%, by value, of the hardware in a typical U.S. personal computer system comes from Asia.6

Cross-border capital flows have likewise grown to unprecedented levels, reflecting reduced barriers to capital, an increased desire of investors to diversify their portfolios internationally, and a plethora of new financial instruments and technologies.7 One survey reports that average daily turnover on world foreign exchange markets rose from $0.6 trillion in April 1989 to about $1.5 trillion in April 1998.8

Official balance of payments data provide a measure of capital flows that, roughly speaking, measure the change in cross-border ownership claims. Figure 2 shows data on inflows of capital to the U.S. by foreigners and outflows of capital sent abroad by U.S. residents. Although U.S. outflows abroad have been rising, foreign inflows have been rising even faster. These cross-border flows typically were no more than 1% of GNP through the 1960s. By contrast, from 1995 through 1998, inflows averaged 7% of GNP.

2. U.S. capital inflows and outflows

Sources: Data from 1923 to 1959 are from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1975, Historical Statistics of the United States, Washington. Data from 1960 to 1999 are from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, various years.

Role of technology and policy

The forces driving globalization include technology and policy. Technological improvements have reduced the costs of doing business internationally; they have also created opportunities for new kinds of commercial transactions, particularly in financial markets and online. At the same time, policy has worked actively to open markets around the world. Together, technology and policy have helped to lower barriers to trade and investment.

Improved transportation technologies have reduced the cost of moving products. For example, the advent of containerization in land- and sea-based shipping has reduced both handling requirements and transit time for deliveries.9 In addition, air transport has become more economical. Worldwide, the cost of air freight, measured as average revenue per ton-kilometer, dropped by 78% between 1955 and 1996.10 At the same time, the share of world trade in high-value-to-weight products such as pharmaceuticals has risen. Reflecting the falling cost of air freight as well as the shifting composition of trade, air shipments in 1998 accounted for 28% of the value of U.S. international trade—up from 7% in 1965 and a negligible share in 1950.11

Improved communications and information technologies have also facilitated international commerce, particularly trade in services. In 1930, a three-minute phone call from New York to London cost $293, measured in 1998 dollars.12 By 1998, one widely subscribed discount plan charged only 36 cents for a clearer, more reliable three-minute call.13 Firms’ ability to provide customer support by telephone or e-mail at relatively low cost, or to transmit digital products electronically via the internet, has reduced the importance of market proximity in some industries.

Improved communications and information technologies have also underpinned rapid financial market developments. The range of financial instruments has exploded in recent years, contributing to the massive gross flows of financial capital discussed earlier. For example, advances in computing technology enable traders to implement complex analytical models. This in turn allows financial firms to meet demand for new financial instruments, such as swaps, options, and futures, which allow market participants to better manage their risk.

Given the economic and technological forces behind globalization, its rise may seem inevitable. Yet governments have taken on a critically important role in opening markets and removing distortions, thereby allowing market forces to play themselves out. In contrast, policy during the interwar period actively promoted protectionism through high tariff and nontariff barriers.14 Indeed, rising protectionism in a number of countries—including the U.S. through the Tariff Act of 1930 (Smoot–Hawley)—made the Great Depression more severe. Despite U.S. efforts to begin reducing tariffs at home and abroad in 1934, through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, world tariffs remained high on average.

For the past half century, in contrast, policy has worked actively to remove barriers and distortions to the market forces underpinning trade and investment. For example, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and, more recently, the World Trade Organization have championed trade liberalization. Since the 1970s, most industrial countries have removed most controls on international capital movements, and many developing countries have greatly relaxed theirs.

Globalization and living standards

Economists generally argue that openness to the world makes us more prosperous. The freedom of firms to choose from a wider range of inputs, and of consumers to choose from a wider range of products, improves efficiency, promotes innovation, encourages the transfer of technology, and otherwise enhances productivity growth. Through trade, countries can shift resources into those sectors best able to compete internationally, so reaping the benefits of specialization and scale economies. Countries on both sides of a transaction stand to gain.

Some, but not all, of the benefits of market opening are quantifiable. For example, recent studies that evaluate trade liberalizing measures under the Uruguay Round of multilateral negotiations, completed in 1994, tend to focus on the effects of reducing tariffs and export subsidies and eliminating quotas. These studies, which capture only a narrow range of the possible gains, find that annual global income could rise on the order of $200 billion, measured in 1992 dollars.15

Opening domestic markets to global capital can also improve living standards. Global capital markets allow investors to allocate their resources where the returns are highest and to diversify their portfolios, thereby reducing their risk. At the same time, countries receiving capital inflows can develop more quickly, since the inflows allow them to increase their productive capital stock without foregoing current consumption. When the capital inflow takes the form of foreign direct investment, the inflow often improves access to international best practices in production, including managerial, technical, and marketing know-how. Therefore, global investment, like trade, benefits both sides of the transaction. These benefits, in turn, can lead to higher real incomes and wages.

Of course, economic globalization is not an end in itself but rather a means to raise living standards. Like other sources of economic growth, including technological progress, economic integration involves natural trade-offs. The same processes that bring about economic growth can force costly adjustments for some firms and their workers. Increased trade re-sorts each country’s resources, directing them toward their most productive uses, but some industries and their workers may face sharp competition from other countries. Overall, however, economists generally attribute only a small share of worker dislocation in the U.S. to trade, roughly 10% or less.16 (Such challenges may, of course, be greater in some other countries, particularly those where entrenched cultural and institutional barriers restrict the mobility of workers.) Nevertheless, crafting sound domestic policy to help ease the transition for those affected poses a significant challenge.

The emphasis here on domestic policy is intentional. Even in an increasingly global economy each nation largely controls its own destiny. Sound domestic policy plays an important role in ensuring that the benefits of international economic integration are shared widely, raising living standards within and across the countries that take part. In large measure, active participation in international markets for goods, services, and capital strengthens the case for domestic policies that make sense even without integration. Among these are policies that encourage a flexible and skilled workforce, provide an adequate social safety net, reward innovation, and secure the integrity and depth of the financial system.

Conclusion

For centuries, rising prosperity and rising integration of the global economy have gone hand in hand. The U.S. and much of the rest of the world have never before been as affluent as today. Nor has economic globalization—the worldwide integration of national economies through trade, capital flows, and operational linkages among firms—ever before been as broad or as deep. Keynes’ description of London at the beginning of the 20th century rings even truer for the U.S. and many other countries today. This conjuncture of rising wealth and expanding international ties is no coincidence. The U.S. has gained enormously from these linkages. Indeed, future improvements in Americans’ living standards depend in part on our continued willingness to embrace international economic integration.

Over the long term, increasing our standard of living in the U.S. requires that Americans embrace change. It is clearly in our interest to forge ahead, both promoting and guiding the process of international economic integration. Yet even as we actively promote and encourage global economic linkages, we must confront the very real challenges that arise from economic globalization. We must find ways to share its benefits as widely as possible. The key lies in maintaining an economy that is sufficiently flexible and vibrant to meet the challenges of reaping those benefits. Ultimately, our prosperity in the global economy depends primarily on our policies at home.

Notes

1 This Chicago Fed Letter draws heavily on chapter 6 of Office of the U.S. President, 2000, Economic Report of the President, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, February. The authors wish to thank Yu-Chin Chen, John Goldie, and Robert Lawrence for their assistance and insight in preparing the original text.

2 John Maynard Keynes, 1919, Economic Consequences of the Peace, London: Macmillan, available on the internet at www.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3ll3/keynes/peace.htm.

3 See, for example, the discussion and references in Michael Bordo, Barry Eichengreen, and Douglas Irwin, 1999, “Is globalization today really different from globalization a hundred years ago?” Brookings Trade Forum 1999, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, pp. 1–50.

4 Douglas Irwin, 1985, “The GATT in historical perspective,” American Economic Review, Vol.85, No. 2, pp. 323–328, provides an overview of the pre-World-War-I and interwar periods.

5 See David Hummels, Jun Ishii, and Kei-Mu Yi, 2001, “The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade,” Journal of International Economics, forthcoming; Catherine Mann, 1999, Is the U.S. Trade Deficit Sustainable?, Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, pp. 39–41; Robert Feenstra, 1998, “Integration of trade and disintegration of production in the global economy,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 31–50; and others.

6 McGraw-Companies and the U.S. Department of Commerce, Inter national Trade Administration, 1999, U.S. Industry and Trade Outlook ’99, p. 27-1 and p. 27-5.

7 Maurice Obsfeld and Alan Taylor, 1998, “The Great Depression as a watershed: International capital mobility over the long run,” in The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century, Michael D. Bordo, Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White (eds.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 353–402, emphasize that net capital flows across countries (as measured by current account balances relative to GDP) were larger in the late 19th and early 20th centuries than they are today. By contrast, Bordo, Eichengreen, and Irwin, op cit., emphasize that gross capital flows—our focus in this Fed Letter—are much larger today than ever before.

8 Bank for International Settlements, 1999, Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Activity, available on the internet at www.bis.org, May.

9 Containerization, as it is called, allows a standard-sized container to be hauled by truck or rail and then, if continuing overseas, loaded by crane directly onto a ship. For more on the transformation of shipping, see, The Economist Newspaper Limited, 1997, “Schools brief, delivering the goods,” The Economist, available on the internet at www.economist.com, November 13.

10 Economic Report of the President, op cit., p. 209, cites data from David Hummels, 1999, “Have international transportation costs declined?” University of Chicago, unpublished paper, as well as personal correspondence from Hummels.

11 David Hummels, 1999, “Have international transportation costs declined?,” University of Chicago, unpublished paper, p. 7, and the U.S. Department of Commerce, various publications.

12 For historical data on the nominal price of a telephone call, see U.S. Department of Commerce, 1975, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Part 2, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 791.

13 U.S. Federal Communications Commission, 1999, Trends in the U.S. International Telecommunications Industry, Washington, DC, table 16.

14 See Irwin, op cit.

15 These estimates cover only a narrow range of the potential benefits from the Uruguay Round. See Council of Economic Advisers, 1999, “America’s interest in the WTO,” white paper, p. 22, citing results in Glenn W. Harrison, Thomas Rutherford, and David G. Tarr, 1996, “Quantifying the Uruguay Round,” p. 238, and Joseph F. Francois, Bradley McDonald, and Håkan Nordström, 1996, “The Uruguay Round: A numerically based quantitative assessment,” pp. 282–283, both in The Uruguay Round and the Developing Countries, Will Martin and L. Alan Winters ( eds.), London: World Bank and Cambridge University Press.

16 Council of Economic Advisers, 1999, “America’s interest in the World Trade Organization: An economic assessment,” p. 14, citing the Economic Report of the President, 1998, pp. 244– 245, and other sources.