The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

On September 28, 2001, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago hosted a conference titled “Are Central Cities Coming Back? The Case of Chicago.” The one-day symposium brought together researchers and real estate business leaders to discuss trends in central city growth. Recently released 2000 census data indicate that population decline in most large central cities of the Northeast and Midwest has slowed and in some cases reversed. This marks a significant change from the trend in the 1970s and 1980s. This Chicago Fed Letter summarizes the presentations at the conference.

Academics’ Chicago

Curt Hunter, director of economic research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, noted in his introductory remarks that the events of September 11 added a dimension to the question of central city vitality that we had not anticipated when planning this meeting—i.e., whether cities and their high densities would continue to be as desirable (for security reasons) as they once were. For the long term, Hunter advanced the following optimistic view: “We should always hesitate to write a great city’s epitaph. Throughout history, we find them experiencing shocks and even devastation, yet most often cities find a way to survive, to reinvent themselves, and to rebuild.” He said he expects lower Manhattan to rebuild and surpass its former glories, in much the same way that Atlanta recovered from the American Civil War, San Francisco from its earthquake, and Chicago from its great fire. More recently, the Chicago area and the greater Midwest region have had to rebuild from the economic upheaval during the 1970s and early 1980s, when capital investment and employment flowed heavily to other parts of the country and the world. At the same time, both population and jobs were leaving the city for the suburbs. While these were tough times for the city of Chicago, Hunter said, the seeds of the city’s rebirth lie in the developments at the Chicago Board of Trade and the other exchanges in the early 1970s. These financial exchanges have made Chicago the risk-management center of the financial industry worldwide. More recently, Chicago has been building strengths in other business services, such as meeting/travel, management consulting, accounting, and legal services.

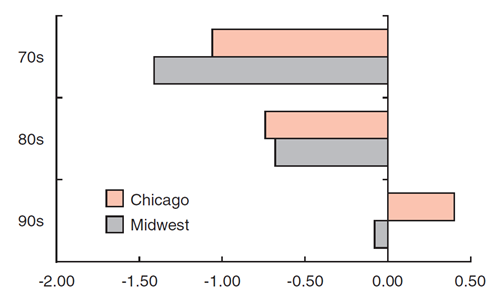

William Testa of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago presented an overall assessment of central Chicago’s performance since 1970. Has Chicago come back? The answer is an unqualified “yes,” as evidenced by population growth, new housing construction activity, location of jobs, workforce status of city residents, and mean household income (see figure 1). A more interesting question is whether any underlying structural improvements have taken place. Testa compared Chicago with eight other large central cities in the region. While large central city performance has improved on average across the region, Chicago’s performance was more robust during the 1990s, especially in terms of population growth and new housing units. The city of Chicago also appears to have improved its job and population performance compared to its own outlying suburban area in the 1990s. Testa concluded that Chicago’s improvements are not due solely to the robust growth experienced by the broader Midwest region.

1. Annual average growth in population

On the issue of underlying restructuring, Dan McMillen from the University of Illinois at Chicago investigated the extent to which housing prices increase with greater proximity to Chicago’s central business district. During the 1980s, housing appreciation displayed little tendency for upward bias in locations closer to the city center. However, by the end of the 1990s, proximity to the central city had become very important to housing prices, which declined by 7.5% for each mile away from the Central Business District (CBD). This trend no doubt reflects the ongoing process of gentrification affecting some formerly low-income Chicago neighborhoods.

John McDonald from the University of Illinois at Chicago outlined a supply and demand model for real estate, using population, household employment, real estate development, and occupancy and vacancy rates to estimate demand. His research identifies an underlying and continuing trend toward suburbanization, even while the city has rebounded. In the suburbs, commercial growth appears to continue to be clustered along the highways, while the new residential growth tends to be filling in between the highways. Meanwhile, the rising tide of metropolitan area growth has lifted all boats, including the city center. McDonald also noted that population growth in the city of Chicago was not uniform among neighborhoods. Ethnic neighborhoods have experienced an influx of population, consistent with national trends (nationwide immigration levels have soared to levels exceeding the early decades of the 20th century). Population growth was also strongest on the north side, and on those south side areas closest to the CBD—evidence that is again consistent with observations of gentrification—high-income and mostly childless households began to resettle the urban core to a significant extent in the 1990s. McDonald hypothesized that traffic congestion may be a factor here. Commuting from afar to downtown Chicago has become overly costly in terms of time and aggravation, inducing many households to opt for a center city residential location.

Jan Brueckner of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign offered a competing hypothesis as to why gentrification was taking place. He argued that high-income households have come to value the amenities that central city Chicago offers and have therefore outbid lower-income households for central city locations. In addition to recent improvements in Chicago’s recreation amenities and city services, reported crime has diminished markedly in Chicago (and across the nation). Brueckner concluded by posing the question of whether a city policy of fostering amenity growth could help extend or at least solidify the gains in the central city.

Edwin Mills from Northwestern University asserted that the population revival in Chicago is a transitory blip that will not in all likelihood be sustained. He argued that the revival is largely due to the robust economic growth and tight labor markets the Midwest enjoyed in the 1990s. However, in the long term, he said he expects the interregional ascendancy of the South and the West to continue. Furthermore, much of Chicago’s population growth has resulted from an inflow of Hispanic immigrants, who tend to be lower-skilled and lower-income workers, and therefore not engines of long-term gentrification. In terms of the prospects for large scale sustained gentrification, Mills claimed that restrictive zoning will continue to preclude high-income people from moving to the city or from expanding the few enclaves that they now inhabit. He rejected arguments for Chicago’s amenities becoming increasingly attractive, saying that these amenities have been in place for a long time in much their current form and fashion.

Other participants noted that one of the most difficult struggles for Chicago is the quality of public education, which continues to deter homebuyers. Some participants expressed concern that Chicago government was not moving quickly enough to ensure that the proper zoning regulations are in place for both residential and commercial space. Others suggested that “people were following new jobs” in their choice of residence near the CBD. The replacement of retail with office employment in the CBD and job growth more generally were identified as an important reason for increasing demand for nearby housing.

Chicago—A real estate view

The second conference panel focused on Chicago’s real estate market. John Jaeger from Appraisal Research Counselors reported on extraordinary growth in residential construction activity in areas adjacent or near the CBD and along the lakefront. Residential availability in these areas increased from 48,650 total units in 1991 to 60,117 total units in 2000. Available rental units have declined due to condo conversions in all areas except River North, the fastest growing enclave near downtown. The most notable increase in units due to new construction took place in the late 1990s. Chicago has historically had a strong residential base and is currently desirable for residential construction due to land and zoning availability, low prices relative to other large cities, a wide variety of cultural amenities, and a school system that is (slowly) improving.

Walter Page of Equity Office Properties Trust explained that for decades suburban total job growth has well exceeded downtown total job growth, with an even more pronounced trend for office employment. A significant challenge for Chicago’s center is whether it can absorb the recent new office space building boom.

Jacques Gordon from LaSalle Investment Management discussed the impact of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center on commercial real estate in central business districts. Gordon reported that his clients are still sorting through issues such as whether they should concentrate their operations in a single building or spread them out over a larger geographic area. He identified a number of short-term and long-term impacts on both occupiers/users and investors/ developers. Some of the short-term impacts, such as delayed real estate decisions, could also be normal responses to a slowing economy, making it difficult to determine the true impact of September 11. Long-term effects could have profound implications for development in Chicago and other central cities. In addition to bearing added security and insurance costs, perhaps as much as $2 per square foot, many companies and organizations are seeking to spatially spread their operations so as to back up or duplicate activities in the event of a work interruption or disaster. There is likely to be an increased demand for teleconference facilities and broadband connections. In addition, some premier skyscrapers may experience lower demand and command lower rents.

Don Faloon from Prime Group Realty Trust discussed the importance of the physical structure of a city’s buildings and described how design has changed in response to changing company needs. The major cost of doing business is employee compensation, and there are a number of ways in which the physical environment of the workplace affects productivity of employees. Design features can directly contribute to employee satisfaction and enhance productivity. For example, placing heating and cooling, electrical, and communication systems in an underfloor design can improve air quality, reduce building costs, allow a reduction in the lease area per person, allow for greater flexibility and reduced cost in changing floor designs (life-cycle cost), and allow employees more control over the temperature of their workspace. Taller ceilings with more windows can reduce the need for lighting fixtures and provide employees with more desirable natural lighting. One issue for Chicago is that current building code restrictions limit the use of manufactured wiring systems (“modular” wiring systems), which reduce first costs and life-cycle costs.

Understanding cities

Ed Glaeser of Harvard University suggested that to understand city performance—past and future—we must first understand the functions that cities serve. Why does the mutual proximity of people in dense configurations give rise to value and wealth? In particular, Glaeser said, we might think of cities as reducing the “transportation costs” for moving goods or commodities, for delivering services to people, and for transferring/creating ideas and information. Cities were created to serve some combinations of these purposes, and their prospects are closely related to these various transportation costs. Costs of transporting goods have fallen markedly over the past century. Therefore, cities created to minimize those costs, such as port cities of the Great Lakes, are generally not faring too well. Service delivery costs may be increasing in many cities as roadway congestion is increasing commuting costs. Warm and dry climates are increasingly valued by higher-income households, while air conditioning allows these services to be delivered or enjoyed more readily. Accordingly, climate continues to be a durable explanatory factor in explaining which cities are growing. Finally, technological improvements such as computers and broadband communications are allowing information and ideas to be transmitted more cheaply. So far, cities have not suffered deconcentration from these trends because face-to-face communication activity has also increased sharply. Glaeser cites research indicating that cities with the greatest concentrations of college-educated workers have grown the fastest, reflecting heightened productivity of those who transmit ideas. Nonetheless, over the longer term, as communications technology progresses, the need for very dense configurations of higher-skilled workers may lighten.

Policy and the cities

Have federal policies assisted with urban revival in the 1990s? Susan Wachter of the Wharton School identified five specific areas of federal policy as proactive and helpful. First, community development block grants target urban areas and downtowns. Second, the earned income tax credit—which expanded greatly during the 1990s—has been a significant contributor to increased household incomes in cities. Third, federally authorized welfare and unemployment policies have increased competition among states and given them (customized) control, leading to better programs. Fourth, a shift to section 8 or to vouchers has facilitated a decrease in the concentration of low-income households. Finally, the Federal Housing Authority, the Community Reinvestment Act, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac dramatically increased homeownership among low-income households in the 1990s; homeownership surpassed 50% of households for the first time in U.S. history during the 1990s.

At the very least, then, federal policy was no longer a negative in the 1990s. Federal assistance with other local service responsibilities—especially crime control—may also have contributed. Wachter asked whether the federal government can now play an assisting role with the primary obstacle to city rebirth—elementary and secondary education.

William A. Fischel of Dartmouth College discussed the importance of zoning and land use policies in the successful redevelopment of central cities. In recent years, redevelopment and reuse efforts have been hindered by so-called NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) responses to redevelopment proposals. While close attention at the neighborhood level to public issues often serves the community well, in some cases it may hinder desirable real estate developments, such as job-generating land redevelopment. Fischel said that the public sector may be able to take some steps to redress this problem. For example, Oak Park successfully resolved a racial desegregation concern by offering homeowners an equity insurance program. Under such programs, homeowners are insured for a possible drop in value in the event that the project fails. Whether an equity insurance program can be carried out by private land-developers remains an issue.

Terry Clark of the University of Chicago concluded the conference program by suggesting that city mayors and the emergence of a “new political culture” could explain some of the gains made by cities in the 1990s. This new culture encourages mayors to form alliances with neighborhood leaders, businesses, and community institutions to improve the quality of life and the available amenities of cities. This model recognizes that cities exist to support and attract human capital. Today’s educated and often high-income workers are footloose, choosing among cities for their amenities and quality of life— safety, recreation and entertainment, personal mobility, and architectural esthetics. Assisted by a demographic trend of often older, often childless, and mostly educated two-earner households, a new generation of mayors has tapped into the desire for urban living. Employment and new business formation have generally followed this labor force into the city.

Summary

In summing the discussion, many conference participants agreed that it is difficult to distinguish the effects of public policy from those of fundamental economic and demographic shifts; further research will be needed to understand central city revival in the 1990s. While some discussants supported the hypothesis that both better amenities and demographic happenstance have assisted Chicago’s revival, others were emphatic that economic regeneration in the CBD has pulled along the city in the 1990s. Chicago’s CBD has prospered from the rapid growth of business service industries that began in the 1980s and continued through 2000; an intense concentration of specialized legal, management consulting, accounting, communication, business education, meeting/travel, and other services has bolstered Chicago’s position as the commercial capital of the mid-continent. Highly educated workers, especially new entrants, flock to the city because it offers a wide and advantageous range of opportunities, along with an exciting and comfortable urban residential lifestyle. The several “edge city” complexes of employment may be linked to Chicago’s CBD, if not in trading relations and sharing of the workforce, then in sharing the bounty of Chicago’s mega-airport facilities and other key infrastructure, such as the region’s telecommunication backbone. Meanwhile, other Midwest cities continue to be at a disadvantage in their industry mix—which remains concentrated in production manufacturing rather than in business services. The city of Chicago has also received a large influx of immigrants relative to other Midwest cities. Overall, there was no consensus among the conference participants as to whether Chicago will continue to prosper in the current decade. Some expressed the view that the underlying trends that have boosted central city Chicago may serve as building blocks on which Chicago and other central cities can fashion successful growth and development policies in the years ahead.