The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

In October 1999, the world’s population nudged past the 6 billion mark, according to United Nations (UN) estimates.1 As this publication goes to press less than two years later, an additional 160 million plus individuals have been added to the tally—a number that is roughly equivalent to the current combined populations of France, Spain, and the U.K. Even more striking is the fact that it took less than 40 years for the world’s population to double from 3 billion people in 1960. Can we expect the population to continue to grow at this pace? And what are the implications of current and projected population growth for the world economy and the economies of individual countries and regions?

In this Chicago Fed Letter, I present an overview of a selection of developments in the world’s population growth, with particular emphasis on the post-1950 period. Second, I outline a set of economic issues (by no means all) associated with demographic change that are facing a number of the major regional/national economies. Finally, I suggest several economic issues likely to arise as a result of population changes as we look forward. I hope to shed some light on the great diversity in the world’s demographics and the dangers of viewing the dynamics of population change in one nation or region in isolation from other nations or regions. This is an area of study that not many economists have explored.2 Perhaps more should.

World population quadruples in one century

Demographers generally agree that the world’s population first reached the 1 billion mark less than 200 years ago—in the early 1800s. The next billion came relatively quickly by historical standards, accumulating in a little over one century—UN demographers estimate that the world’s population reached 2 billion in the late 1920s. Since then, the “miracle” of compounding (facilitated by advances in health care, gains in life expectancy, and markedly higher economic output and income in major portions of the world) has had a conspicuous impact on the world’s population. From the late 1920s it took only another approximately 33 years for the world’s population to reach 3 billion in 1960. Then, in less than 40 years—1960 to 1999—the world’s population is estimated to have doubled to 6 billion people. Within that span of time the surge in population may be characterized by two periods of exceptional growth—one in terms of growth rate and one in terms of absolute numbers.

The first of these exceptional periods occurred between the years 1961 and 1974, when the world’s population growth rate averaged an unprecedented 2% per year. The net addition to the world population during that span is estimated at 930 million individuals; in perspective, this is a number that approaches the current aggregate population of the third through seventh most populous nations in the world—the U.S., Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, and Pakistan.

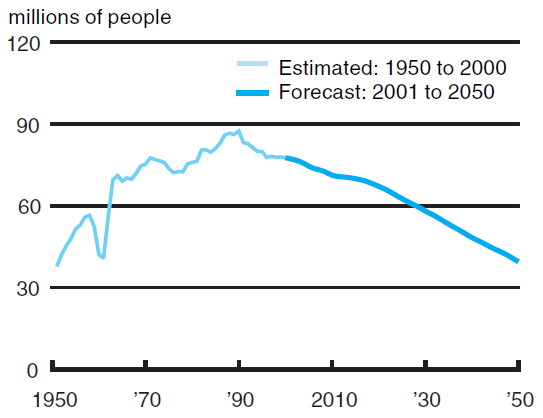

The second period of phenomenal growth occurred a little later as the rate of growth began to moderate—1981 through 1994—a period during which the incremental increase in population peaked and averaged nearly 83 million people annually (figure 1). Again, in perspective this annual increase was equivalent in size to the current population of Germany.

1. World population, net additions

Population growth rates have slowed progressively during the past two decades to a rate of around 1.2% per year currently. And the annual net additions have moderated somewhat to around 77 million. Still, gains of this magnitude are equivalent to adding the combined population of Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands to the world total each year. Given the size of the population base in place, even progressively reduced rates of increase will result in substantial numerical additions to the world’s population and the demands on its resources for many years to come. This is reflected in UN forecasts, which show the world’s population increasing another 3 billion—approaching 9 billion—by 2050 (a good portion of that total has already been born). Thereafter, according to the UN’s current best guess, continued although marginal annual increases will occur until the world total stabilizes at a little over 10 billion people around the year 2200.3

One might expect that the allocation of the world’s resources in order to support a 43% increase (3.3 billion people) in population during the next 50 years could pose a formidable challenge. However, during the past 50 years the world’s economies have absorbed an 88% increase (3.5 billion people) in population and at the same time have managed to generate an increase in annual real incomes of around 3.8%, on average (World Trade Organization estimates). So, what’s the problem? As it has been during the past 50 years, the devil is in the details. During the late 1990s and in the early years of this decade the world’s populations have been approaching a watershed that potentially has significant implications for the demographic distribution across nations and the consequent economic conditions of those nations. The 3 plus billion people expected to accumulate during the next 50 years will face a very different demographic/economic environment from that of the last half of the twentieth century. What are some of those differences?

Increase in dependent populations

An aging population

In the U.S., discussion of an aging population tends to focus on the structure and funding of intergenerational income transfers through the social security system, whereby a larger proportion of the population ultimately will be drawing benefits that are partly financed by a relatively smaller proportion of the population. While this demographic and economic environment may constitute a formidable challenge for U.S. policymakers, they will not have to deal with the rather difficult implications of a declining population (declining because of lower birth rates and, eventually, a relatively smaller population in the productive workforce). An older and declining population is an environment set to face a number of the world’s economies in fairly short order. Indeed, several Western and Central European countries, as well as Japan and South Korea (even China by 2050) are crossing or soon will cross the divide; thereafter they will experience not only a relative increase in their dependent aging population but the compounding effect of a declining overall population.

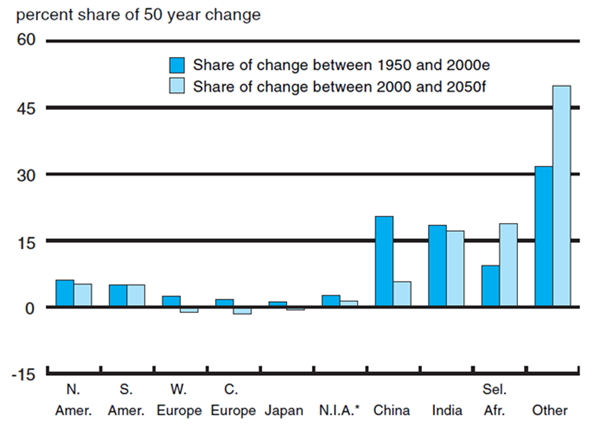

For example, the population of Western Europe in 2015 is expected to be little changed from that in 2000. Within Europe’s aggregate population of 388 million, the UN’s current forecast predicts that by 2015 a 5-million-person aggregate decline in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland will be just offset by increases in the other 12 major countries in this grouping. However, by 2050, the population in these 17 countries is expected to have declined by 38 million people, a 10% reduction relative to the year 2000 (figure 2). This absolute decline in population will occur as the impact of declining fertility rates (number of children per woman of childbearing age), currently below replacement rates throughout virtually all of Europe, eventually takes hold and turns population growth negative.

2. Change in world population

Notes: e indicates estimate, and f indicates forecast. Sel. Afr. indicates selected countries in Africa.

Source: United Nations.

These below-replacement fertility rates are expected to more dramatically affect several of the middle-income nations in Central and Eastern Europe. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Russia, in the aggregate, are expected to lose nearly 14 million people between 2000 and 2015, and an additional 37 million by 2050. Should declines of this magnitude occur, they would constitute a 29% drop in population between 2000 and 2050.

On the other side of the globe, Japan’s population is expected to increase marginally between 2000 and 2015 and then, by the year 2050, to drop to 109 million people from a population of 127 million in the year 2000, an overall decline of 15%.

As challenging as these changes in population composition may be, arguably, most of these countries are comparatively well off economically. A more difficult challenge might appear to be facing many of the low and lower-middle income nations of the “third world”—nations that, during the period 2000 to 2050, are expected to contribute between 60% and 80% of the more than 3 billion net addition to world population.

Gains in the young and the old population

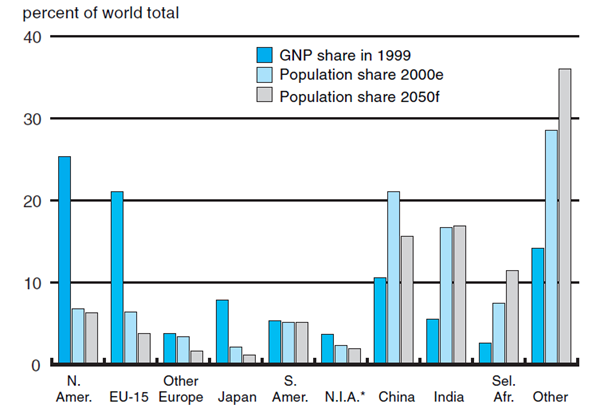

Third-world countries currently account for only about one-third of the world’s real economic output but are home to nearly three-quarters of the world’s population (figure 3). However, by 2050, according to current forecasts, these countries are expected to contain four-fifths of the world’s population. Age dependency in these nations will remain tipped toward the young, but they also will face increasing pressure from an aging population—China in particular.

3. GNP and population shares by region

Notes: e indicates estimate, and f indicates forecast. Sel. Afr. indicates selected countries in Africa.

Source: United Nations and World Bank.

China deserves a special note with regard to the aging population growth discussion. It is somewhat of an anomaly in that it appears to be going through a major transition with regard to population growth that is unusual for a country firmly planted in the lower-middle-income class of countries. During the period 1950 to 2000, China’s population more than doubled to just under 1.3 billion people.

In response to the magnitude of the nation’s population and its continued rapid increase during the second half of the century, the Chinese government instituted a policy in the early 1970s that encouraged couples to start families later and to have fewer children (the “later-longer-fewer” policy). Then in 1979 the government implemented a more specific restrictive population policy, commonly known as “one family, one child.” The results of these policies were dramatic. It is estimated that in the early 1970s China’s fertility rate was greater than 5.0; by 1979 the rate had dropped to less than 3.0. It is estimated to have dropped to 2.2 by 1990 and to a less than replacement rate of 1.8 in 1992, where it has since remained. According to UN projections, China’s population will peak during the 2000–50 period and decline marginally between 2025 and 2050—from 1.47 billion to 1.46 billion. One of the results of this shift in policy will be that China will shift rather quickly from its late 1900s youth-dependency status to an aged-dependency status by 2050. As such, the country will increasingly face the economic pressures of relatively fewer productive workers supporting a very sizable older, dependent population.

In sum, while the industrial countries can expect to face a surge in the relative size of older dependent populations, the poorer third-world countries can expect to face not only an increase in older dependent populations but also, in many cases, a continued large proportion of young dependents. The disturbing point of this is that the greatest increases in dependent populations (whether young or old) are likely to occur in those economies that are least able to support them.

Are these forecasts reasonable?

Current U.N. forecasts indicate that by 2025 the world’s population will likely approach 8 billion. And while demographers expect that population growth rates will continue to slow, eventually reaching a steady state replacement rate, U.N. medium estimates for the world’s total population indicate that it will continue to increase to around 9 billion by the year 2050. Eventually it is expected to stabilize at a little over 10 billion around the year 2200. As with any forecast, the assumptions underlying it are critical. Key assumptions include expected changes in fertility rates (number of children per woman of childbearing age), life expectancy, impact of diseases such as HIV/AIDS, and trends toward urbanization.

Where do we go from here?

As noted earlier, the population challenges facing the U.S. pale in comparison to those facing many other regions of the world, be they industrial or developing. Western and Central Europe face not only an aging population, but also the compounding influence of a declining population. What are the political/economic implications of a proportionately older yet smaller population in a Europe in the throes of economic, social, and possibly political integration? This is a population that may drop from about 450 million in 2000 to about 400 million in 2050. (If Russia were included in this total, the decline would be from nearly 600 million to a little over 500 million.) What form of economic pressures would such a decline place on European unification and on its ability to compete economically and politically in the world arena? Japan, with an estimated 15% decline in its population over the next 50 years, potentially faces similar political/economic issues.

Probably most disconcerting is the increase in dependent populations facing the poorest countries of the world, in particular the bulk of Africa and nonindustrial Asia. The bulk of the world’s 3 billion population increase will accumulate in these regions. In addition, the proportion of dependent population (age 15 and under and age 65 and over) in these regions is expected to increase substantially, a development that will hinder their ability to increase incomes above mere subsistence levels. What does this imply for economic and political stability in these regions?

Conclusion

Economics, as a profession, has not paid a lot of attention to the impact of compositional change in populations. In recent years the aging of the U.S. population has begun to garner attention with the realization that a large new dependent population would soon begin to draw increasingly on the nation’s productive resources.

What does this development mean for the nation’s economic expansion overall? How does this aging of the population affect different industrial/services sectors and geographical regions of the national economy? What is the impact of an aging and/or declining population on the political/economic desirability of promoting immigration? For example, would the promotion of immigration be desirable (and more politically acceptable) from the perspective of high-income countries in order to fill the gap in the younger/productive age groups? However, doing so may pull the “best” of the younger/productive populations from third-world countries that are also facing an aging population—compounding their already difficult conditions. These are knotty issues and will become increasingly so as the first half of this century plays out.

Notes

1 This article draws extensively on the following sources: The World Bank, 2001, World Development Report 2000/2001, Washington, DC; The World Trade Organization Secretariat, 2001, World Trade Developments, Annual Report, 2001; United Nations Secretariat, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 1999, The World at Six Billion, ESA/P/WP. 154, New York, NY, October 12; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999, World Population Profile: 1998, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, report, No. WP/98; U.S. Bureau of the Census website: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www.

2 A notable exception is Professor Gary S. Becker, who has long included population issues in his work (academic as well as popular). On the popular press side, see for example, Gary S. Becker, 2001, “How rich nations can defuse the population bomb,” Business Week, May 28, p. 28.

3 A critical assumption of this forecast is that the fertility rates in all major areas of the world hold at the population replacement level from about the year 2050 onward. The UN study notes that the forecast is highly sensitive to the fertility rate assumption. For example, it points out that a fertility rate of plus or minus one-half child from the replacement rate (about 2.1 children per woman of childbearing age) would result in a world population in the year 2150 ranging from 3.2 billion (about one-third the medium forecast) to 24.8 billion (about two and one-half times the medium forecast).