The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Technological progress has eroded one of community banks’ traditional advantages—the information edge from being located close to their customers. Is the community bank business model still viable in a world where financial relationships do not depend on face-to-face contact? The authors review some of the existing evidence and look forward to a research conference where participants will offer new evidence.

There are more banks per capita in the United States than in any other developed economy. The vast majority of these banks are so-called community banks, identifiable by their small size, their limited geographic reach, and their traditional array of banking services. The central principle of community banking is “relationship finance,” the idea that personal interaction between bankers, small borrowers, and small depositors creates informational efficiencies that allow credit to flow more efficiently and commerce to grow more quickly.

Community banking is consistent with traditional American beliefs that small business and local control of resources are intrinsically good, while concentrated financial, economic, and political power is intrinsically bad. For decades, state and federal banking regulations based on these ideals locked the U.S. banking industry into a system of small, local banks by restricting banks from doing business across state and county borders. As a byproduct, these regulations helped preserve thousands of poorly run community banks by shielding them from outside competitors.

In recent years, advances in communications technology, financial markets, and banking production techniques have reduced the comparative advantages of community banks in collecting local information. In a world with these new technologies, the arguments for protecting local banks from outside competition became much weaker. State and federal legislatures rolled back and eventually eliminated banking and branching restrictions, and the result has been a dramatic restructuring of the U.S. banking system.1 Thousands of community banks have been merged out of existence, and although thousands of community banks remain, the surviving banks tend to be the larger ones.

There are two distinctly different—though not necessarily mutually exclusive—explanations for the declining number of community banks. One explanation contends that the decline in numbers is a long overdue culling of inefficient, poorly managed community banks unable to survive in highly competitive, post-deregulation banking markets. If this is the case, then thousands of well-managed community banks are likely to survive. A second explanation contends that the local banking model is no longer economically viable due to technological change. If this is the case, then the number of traditional community banks is likely to dwindle even further in the future.

This Chicago Fed Letter explores the causes and consequences of the shrinking community banking sector and considers the sector’s future. This article also serves as an introduction to a conference to be held in March 2003, jointly sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and the Journal of Financial Services Research, at which academic and regulatory economists will present new research on the future of community banking.

Fewer community banks: Deregulation and mergers

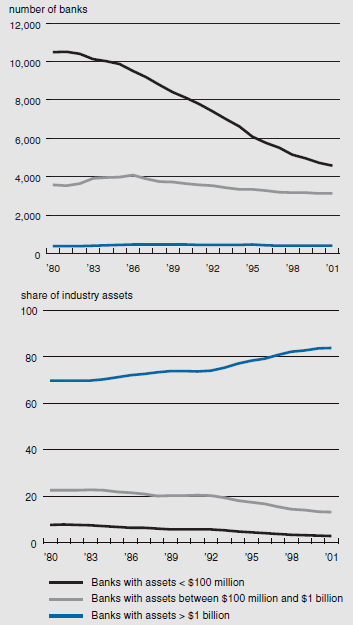

The declining presence of community banks in the U.S. banking system is illustrated in figure 1. The top panel shows that the number of “small” community banks (banks with assets less than $100 million) has fallen from around 11,000 banks in 1980 to less than 5,000 banks today. The number of “large” community banks (assets between $100 million and $1 billion) has declined only slightly since 1980, while the number of “large banks” (assets greater than $1 billion) has held relatively steady.

1. Number and assets (%) of community banks

Sources: Call Report data and authors’ calculations.

The decline in the population of U.S. banks was made possible by geographic deregulation and was implemented via mergers and acquisitions. Mergers between large, well-known institutions have received the most press—for example, the merger of Bank of America and NationsBank in 1998, which created the first coast-to-coast U.S. retail banking franchise—but these “megamergers” account for only about 5 percent of U.S. bank mergers since 1980. In contrast, about 55 percent of the bank mergers during the past two decades combined two community banks.

These mergers would not have been possible without the repeal of federal and state banking regulations that historically restricted the size and geographic mobility of U.S. banks. At first, banks combined across county lines with other in-state banks; later they expanded by making acquisitions across state lines. These market extension mergers more than doubled the geographic reach of the typical U.S. bank holding company2; intensified competitive rivalry in the local banking markets targeted by these mergers3; and concentrated industry assets in a smaller set of increasingly large banks. The bottom panel in figure 1 shows that about 15 percent of total industry assets have shifted from the community bank sector to the large bank sector since 1980.

Fewer community banks: Technological change

As industry deregulation was increasing the degree of competition faced by community banks, emerging technologies were eroding community banks’ traditional informational advantages in local markets.

Community banks rely heavily on local households and businesses for deposit financing. But the emergence of mutual funds, online brokerage accounts, sweep accounts, and other new savings and investment vehicles over the past 20 years has provided would-be bank depositors with a greater array of options, increasing the scarcity of core deposits.4 And because community banks have fewer funding options than large banks—e.g., small banks do not have access to bond markets or commercial paper markets—they must pay higher interest rates (or, equivalently, charge lower fees) to attract and retain deposits.

Community banks have traditionally been the primary source of credit for small, local businesses, chiefly because the creditworthiness of these small firms could be observed only by local banks. But new lending and financial technologies are making it easier for small businesses to transmit information about their creditworthiness to lenders outside the local market. Credit scoring models and online loan applications allow out-of-market banks to gather information about small business borrowers (or mortgage borrowers or credit card borrowers) at relatively low cost, and then manage the risk of those loans by pooling them and selling off portions in securitized asset markets. This “transactions-based” approach to lending exhibits economies of scale, which gives large banks that make high volumes of loans a cost advantage over community banks.

New communications technologies allow large banks to compete in local markets without ever opening local offices, via networks of ATMs, internet kiosks, or transactional internet websites. These nontraditional delivery channels increase the access of local businesses and households to financial services and greatly multiply the number of potential competitors faced by community banks. Recent research shows that the distance between business borrowers and their bank lenders has increased substantially over the past two decades, arguably because of the increased ability of lenders to profitably underwrite and monitor business loans without direct person-to-person contact.5

Whither the community bank?

Will community banks continue to decline in numbers and market share, signaling that the community bank business model is no longer economically viable? Or will these declines slow down in the near future, leaving a long-run population of viable community banks somewhere near today’s numbers?

In a recent study, Robertson (2001) attempts to project the future size distribution of U.S. banks using a complex statistical analysis based on 40 years of industry trends.6 Although he projects that the annual decline in the number of small banks (which he defines as having assets less than $2.7 billion) is slowing down, he also projects that the overall number of community banks will shrink substantially. By the year 2007, Robertson projects there will be only about 2,500 banks with assets less than $100 million (down from about 4,000 today), only about 1,750 banks with assets between $100 million and $900 million (compared with about 2,500 today), and about 500 banks with assets between $900 million and $2.7 billion (about the same as today).

Of course, long-run projections based on past industry trends can be quite inaccurate because they cannot take into account unforeseen changes in technology, prices, market demand, and other factors that influence the structure of the industry. For example, while a merger may reduce the number of banks in a local market, it can also change that market in ways that make it more hospitable to community banks. As documented by Berger and Udell (1996), large banks allocate a relatively small percentage of their assets to small business lending, and this raises the concern that industry consolidation will lead not only to fewer small banks, but also to less credit for small local businesses.7 However, these and other researchers have documented some countervailing effects: Small business customers that are “abandoned” in the aftermath of mergers provide expansion opportunities for local community banks, and are fertile ground for newly chartered, start-up community banks.8 These phenomena suggest there is a lower limit to the size of the community banking sector.

Profitability data from community banks also suggest that a substantial number of community banks will survive. DeYoung and Hunter (2002) found that, between 1996 and 2000, average return-on-equity at the most profitable 50 percent of community banks significantly exceeded the average return-on-equity at large commercial banks with assets greater than $10 billion.9 In other words, half of the current population of community banks appear to be economically viable, all else equal. Moreover, this study found that highly profitable community banks used a different business model than large commercial banks, relying more heavily on core deposits than on purchased funds and relying more heavily on interest income than on fee-generating activities.

The coexistence of highly profitable community banks and large, increasingly complex commercial banks suggests a future industry structure in which there are (at least) two types of profitable business models.10 In one business model, large banks sell high volumes of basic financial products and retail banking services (e.g., origination and servicing of mortgage and credit card loans and online brokerage and investment products), with profit margins driven by the realization of scale economies. In the other business model, small banks sell low volumes of more personalized, high-value-added financial products (e.g., small business loans and personalized investment and trust services), with profit margins driven by the willingness of customers to pay high prices for these services. The number of community banks that can survive using the latter business model is uncertain, but it is likely that successful implementation of this model will require community banks to complement their traditional banking practices with new technologies (e.g., internet delivery) and a wider scope of financial services (e.g., insurance and brokerage).

A research conference on community banking

The driving forces of change in financial services—new technology, less regulation, and growing competition—seem to be stacked against traditional community banks. The number of community banks, and their share of loan and deposit markets, has been shrinking for over a decade. Given these trends, it is natural to wonder whether the community bank business model remains viable. While it is unlikely that community banks will entirely disappear, their numbers are likely to continue to shrink, and those that survive may not look like traditional community banks.

To encourage research on the future of community banks, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and the Journal of Financial Services Research are sponsoring a research conference— “Whither the Community Bank?”—to be held in Chicago on March 14, 2003. Those interested in attending the conference or submitting a research paper can find additional conference information on the Chicago Fed website at www.chicagofed.org.

The conference will address the following questions: If community banks do not survive in their current traditional form, what will be lost? How might future community banks differ from today’s community banks? Will community banks compete directly with large full-service banks, or will they seek out product niches? Will new technologies erase community banks’ traditional information-based and relationship-based comparative advantages, or will technology create new opportunities for community banks? What makes today’s best-practice community banks successful, and will these banks be able to maintain high returns in the future? How much would competition in local markets suffer if community banks disappeared entirely? Are the social and economic benefits of locally based banking more crucial for developed countries or for developing countries? As community banks evolve, what challenges will they pose for supervisors and regulators?

Notes

1 The Riegle–Neal Act of 1994 legalized interstate banking and branching in the U.S., following more than 20 years of ad hoc deregulation by state governments.

2 See Allen N. Berger and Robert DeYoung, 2001, “The effects of geographic expansion on bank efficiency,” Journal of Financial Services Research, Vol. 19, April/June, pp. 163–184.

3 See Robert DeYoung, Iftekhar Hasan, and Bruce Kirchhoff, 1998, “The impact of out-of-state entry on the efficiency of local banks,” Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 50, pp. 191–204; Douglas D. Evanoff and Evren Örs, 2001, “Banking industry consolidation and productive efficiency,” Proceedings of a Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, pp. 216–226; and Gary Whalen, 2001, “The impact of the growth of large, multistate banking organizations on community bank profitability,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, working paper, No. 5.

4 See Hesna Genay, 2000, “Recent trends in deposit and loan growth: Implications for small and large banks,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Chicago Fed Letter, No. 160, December.

5 See Mitchell A. Petersen and Raghuram Rajan, 2002, “The information revolution and small business lending: Does distance still matter?” Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

6 See Douglas D. Robertson, 2001, “A Markov view of bank consolidation: 1960–2000,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, working paper, No. 4, September.

7 See Allen N. Berger and Gregory F. Udell, 1998, “Universal banking and the future of small business lending,” in Universal Banking: Financial System Design Reconsidered, Anthony Saunders and Ingo Walter (eds.), Toronto, Canada: Irwin, pp. 558–627. Other studies have documented the conditions under which lending to small businesses declines after bank mergers: William R., Keeton, 1996, “Do bank mergers reduce lending to businesses and farmers? New evidence From Tenth District states,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, Vol. 81, No. 3, pp. 63–75; Joe Peek and Eric S. Rosengren, 1998, “Bank consolidation and small business lending: It’s not just bank size that matters,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 22, No. 6, pp. 799–819; Ben R. Craig and João A. C. Santos, 1998, “Study of the banking consolidation impact on small business lending,” Proceedings of a Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, pp. 569–588; and Philip E. Strahan and James P. Weston, 1998, “Small business lending and the changing structure of the banking industry,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 22, No. 6–8, pp. 821–845.

8 See Allen N. Berger, Anthony Saunders, Joseph Scalise, and Gregory F. Udell, 1998, “The effects of bank mergers and acquisitions on small business lending,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 50, pp. 187–229; William R. Keeton, 2000, “Are mergers responsible for the surge in new bank charters?,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, First Quarter, pp. 21– 41; and Allen N. Berger, Seth D. Bonime, Lawrence G. Goldberg, and Lawrence J. White, 1999, “The dynamics of market entry: The effects of mergers and acquisitions on de novo entry and small business lending in the banking industry,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, working paper, No. 99-41.

9 See Robert DeYoung and William C. Hunter, 2002, “Deregulation, the Internet, and the competitive viability of large banks and community banks,” in The Future of Banking, Benton Gup (ed.), Westport, CT: Quorum Books, forthcoming.

10 DeYoung and Hunter, ibid., provide a detailed treatment of this industry model.