In communities across America, local policymakers rely on data-driven research to help them gauge potential returns to public investment. But while a wealth of data on schools and infrastructure has made it possible to measure the effects of spending in these areas and others, one area of significant local importance has been historically understudied: investment in public libraries.

In 2018, local governments in the U.S. spent more than $12 billion funding the operation of 17,000 libraries. That same year, children checked out more than 750 million library items and attended library events more than 80 million times.

Thanks to detailed new data on nearly all public libraries and schools in the U.S., we’re able to observe the direct effects of these investments. In a new study co-authored with Gregory Gilpin at Montana State and Peter Nencka at Miami University, we not only show that spending on libraries increases library usage, but also uncover a direct, causal link between spending on libraries and higher student reading scores.

Children still need and use libraries

To study how spending on libraries impacts library usage, we combine data on local capital spending that funds major renovations and new library buildings with data on library spending, revenue, and usage. These data are collected annually by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

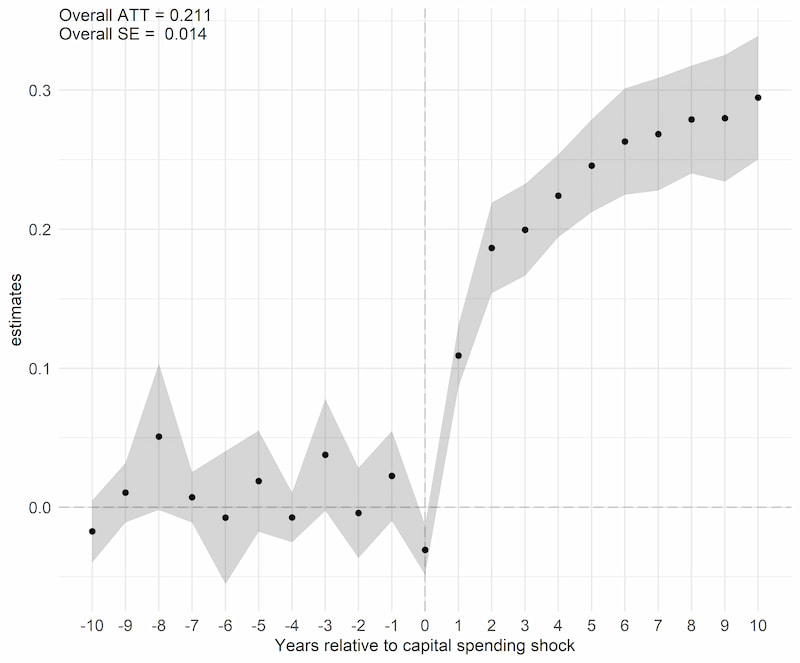

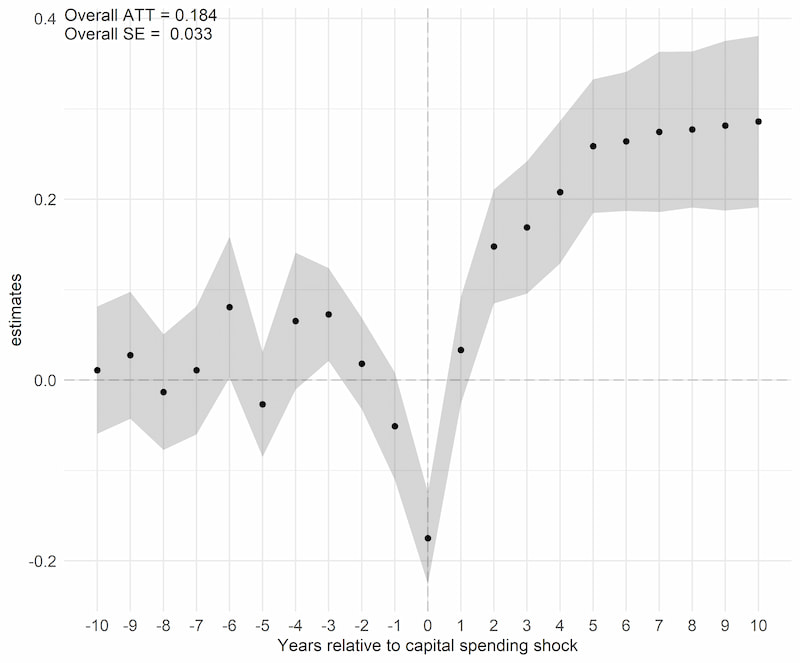

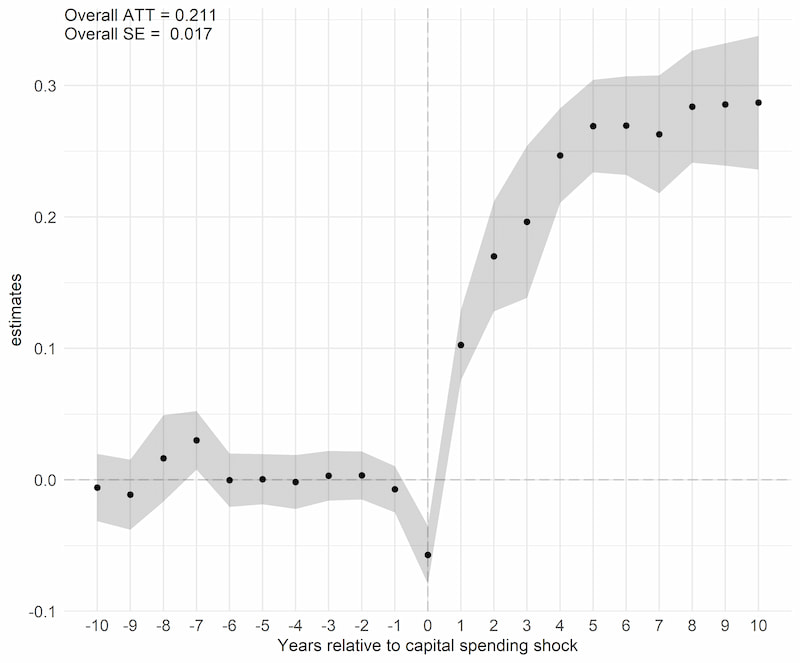

We find that local capital investment in public libraries from 1982 to 2018 increases library visits by 21%, increases children’s checkouts of items by 21%, and increases children’s attendance at library events by 18%. What’s more, these increases in usage persist for at least ten years after the investment.

Log children’s circulation

Log children event attendance

Log visits

These results look the same when we focus on more recent time periods. In short, the research shows that even in the era of the smartphone, there’s a large, untapped demand for local library resources. If you build a library, people—and especially children—will come and use it.

How libraries boost reading scores

Importantly, increases in book checkouts following investments show that communities rely on libraries for much more than computer access. Even today, people use libraries to read.

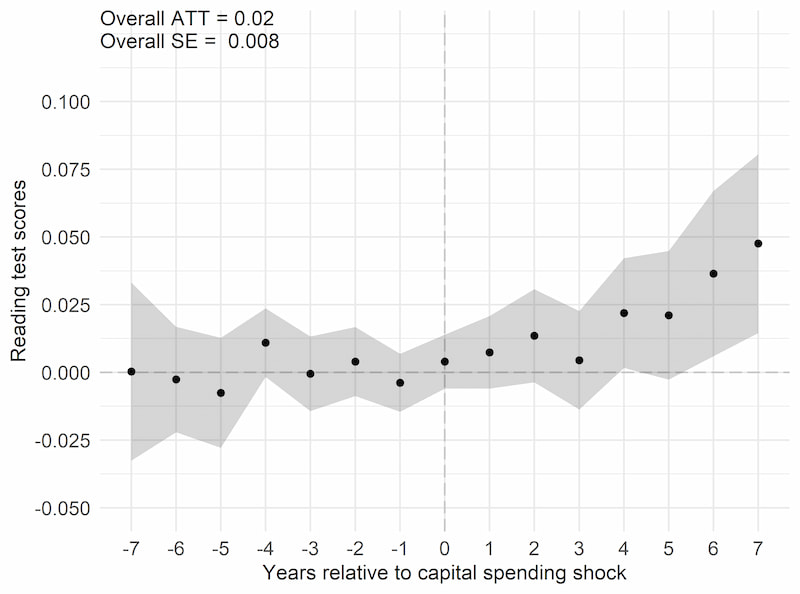

To study whether there’s a causal link between investing in libraries and student outcomes, we analyze district-level reading and math test scores for 3rd–8th graders in more than 5,000 school districts, courtesy of the Stanford Educational Data Archive (SEDA).

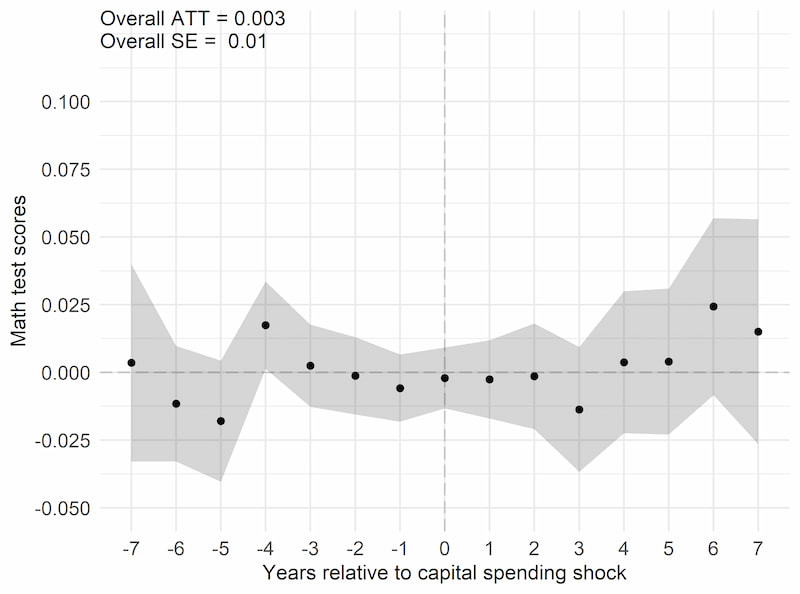

We find that when communities invest $1,000 or more per student in a local library, the reading test scores of students in nearby school districts increase by 0.02 standard deviations, on average, in the seven years following the investment. Unsurprisingly, given libraries’ focus on reading, we find no increase in student math scores.

Reading Test Scores

Math Test Scores

Libraries are an effective, popular public investment

Interestingly, we find that in the years following a large capital investment, spending on libraries has no positive or negative effect on local housing prices, implying that homeowners value the improvement in local amenities enough to offset the cost of the local tax increases that fund the renovations and new buildings.

Taken together, the findings from this new research are good news for library lovers and even better news for communities looking for effective ways to improve young people’s educational outcomes.

Our paper shows that investment in public libraries is an evidence-based way to improve both community resources and student outcomes.

To learn more, download the full paper.