The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

“So near and yet so far away” is an old saying that best describes recent economic trends in Detroit and Chicago.1 Detroit and Chicago are the two largest metropolitan areas in the Midwest with populations exceeding 4 million and 6 million, respectively. Despite their similar size and close physical proximity (at just over 279 miles apart), they have followed much different paths in the Midwest economy. Although both services and technology activities have increased, Detroit has remained largely a manufacturing-oriented town while, to a greater extent, Chicago has shed manufacturing in favor of services, transportation, and trade. Economic performances have also diverged. Over the past two decades, Chicago has held a slight edge in total employment growth, while in manufacturing alone, Detroit’s decline has not been as precipitous.

These differences in structure and performance pose difficult questions for those of us who believe that public policy can influence an area’s industry structure and economic progress. Is the Chicago area’s future clouded by its conversion to a service economy from a manufacturing economy? Or should Detroit try to emulate Chicago by diversifying into a regional and national service center? This Chicago Fed Letter reviews the performance of these metropolitan areas and their roles in the Midwest economy. Evidence of a reawakening underlying each area’s economy suggests that each may prosper by following its own unique path of development policies and programs.

Detroit versus Chicago

In the not-too-distant past, Chicago’s economy was steeped in the manufacturing of steel, metals, machines and tools, and food processing, although the metropolitan area has also long been the trade, transportation, and business service center of the nation’s midland. Recently, Chicago has moved away from its manufacturing specialty and further capitalized on its role as the trade, service, and transportation capital of the region.

In contrast, the Detroit area continues to be characterized today as a manufacturing center rather than a regional or global center for services such as accounting, finance, advertising, and management consulting (see figure 1). Despite its advantages, such as its large size and the fact that it is the corporate headquarters for the Big Three auto companies, the metropolitan area often competes unsuccessfully for business services industries with smaller nearby metropolitan areas such as Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio.

1. Industry concentration

| Chicago area | Detroit area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 1990 | 1969 | 1990 | |

| Nondurable manufacturing | 1.19 | 1.23 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| Durable manufacturing | 1.23 | 0.95 | 2.26 | 2.41 |

| Finance, insurance, and real estate | 1.21 | 1.48 | 0.83 | 0.80 |

| Legal services | 1.38 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| Business services | 1.30 | 1.41 | 1.04 | 1.16 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System.

But the truth is never so simple as broad generalizations might suggest. The Detroit economy has been developing business service activities along with most other large urban areas of the U.S., and in at least one industry—commercial banking—Detroit companies have been growing rapidly and are now successfully competing with firms in Chicago’s own back yard. In addition, as an outgrowth of its auto industry strength, Detroit has been shifting its focus from auto-related production activities toward auto-related technology activities such as research and design. It is becoming a global tech center. In these respects, Detroit’s diversification has been dramatic as well.

Chicago

Chicago has all but abandoned the notion that manufacturing can pull along its economy in the l990s.2 Rather, the Chicago area’s successes in job creation have been outside manufacturing. The growth of O’Hare airport was a major coup in the 1970s and 1980s. Employment has swelled in public building projects associated with air travel such as the convention centers in the city of Chicago and suburban Rosemont adjacent to O’Hare, and so has related employment in hotels, restaurants, retail, and ground transportation. In addition, the air route hubbing of American and United Airlines (the latter is headquartered in Chicago) at O’Hare has contributed to the rapid growth of business services in Chicago such as management consulting and advertising. Business agents in these service industries can easily access and serve clientele throughout the nation using frequent and wide-ranging air connections. Chicago’s commodity exchanges have also been an impetus to Chicago’s economy. The natural growth in existing markets, along with the development of new products such as stock index futures and trading on government Treasury bonds, have expanded employment.

Employment in these activities and other business service activities have concentrated around both its airport and its vibrant central business district, which witnessed an expansion of 31 million square feet of office space (25%) during the 1980s. The central business district has grown outward (south, west, and north) as well as upward.

In looking for future winners in job creation for the 1990s, Chicago need not look very far afield from the 1980s. The commodity exchanges can be expected to thrive along with the development of new products such as futures contracts on sulfur dioxide emission allowances (sulfur dioxide emissions are a cause of acid rain) and urban ozone (i.e., smog) emission allowances and expanding trading hours with the development of the GLOBEX electronic trading system.

Expansion at O’Hare airport and plans for a third airport (possibly to be located at the city’s southeast corner or at a southern metro-fringe locale) will build on the area’s existing base as a transportation hub. A new international terminal at O’Hare and possibly two new runways will add to the metropolitan area’s air connections, which are highly prized by information and service-related businesses. The city also hopes to attract a consortium of casino gambling facilities that will go hand in hand with its travel, convention, and tourism growth of the 1980s and will provide jobs for city residents. The city has finally begun renovating its Navy Pier as another central business and tourist attraction. Perhaps the Navy Pier renovation best illustrates the economic transformation of Chicago—trying to preserve the best of the past, while reworking it to meet the needs of the future.

Detroit

The Detroit area is also undergoing transformation into business service arenas, but the transformation is milder and it differs in character. Its location as the corporate headquarters of the Big Three auto firms has resulted in many local linkages to business service companies. These connections have been magnified of late as corporate headquarters have recently outsourced internal service functions in efforts to trim costs. Nonetheless, Detroit’s transformation to a service-oriented economy is much less complete than Chicago’s; Detroit remains primarily a manufacturing area rather than a regional service center, and its services are closely tied to its manufacturing industries.

Yet, Detroit’s restructuring process has been every bit as dramatic as Chicago’s, but the nature and direction are very different. Owing to its historic concentration in autos, it would be difficult and perhaps even disastrous for the Detroit metropolitan area to stray very far from its transportation industry. Thus, restructuring within the auto industry is a major driving force behind the transformation of its economy rather than solely a change in the mix of industries. Prodded by international competition and lured by revolutionary production and management techniques developed in Japan and Europe, the Big Three and others have adopted new organizational techniques on both the factory floor and in their corporate offices. Some activities, such as design and engineering, are being cooperatively conducted with suppliers. Other changes in supplier relations include increased outsourcing of parts production, both domestically and abroad.

On the factory floor, domestic industry improvements in cost competitiveness and quality have been dramatic, although the impact on the region has been painful in lost income and jobs. Assembly hours per vehicle have been shaved over the course of the 1980s, while defects per car at domestic companies (e.g., Ford) now approach those of the Japanese producers.

Improvements in cost and quality have not been confined to the factory floor. The focus of Detroit industry has shifted to research, development, and design, as evidenced by Chrysler’s new $1.5 billion technology facility in Auburn Hills. Some foreign transplant R&D activity has also been attracted to the area’s automotive environment. Nissan Research and Development Inc. has an $80 million, 340,000 square foot facility in Farmington Hills; Toyota has spent $38 million to expand its technical center in Ann Arbor Tech Park; and Isuzu has targeted a smaller such facility in Plymouth (Mazda and Mitsubishi have added to local staffs without new building). To a more limited extent, factory floor activity such as Ford-Mazda’s Flat Rock facility has also been added to the Detroit area.

The bottom line

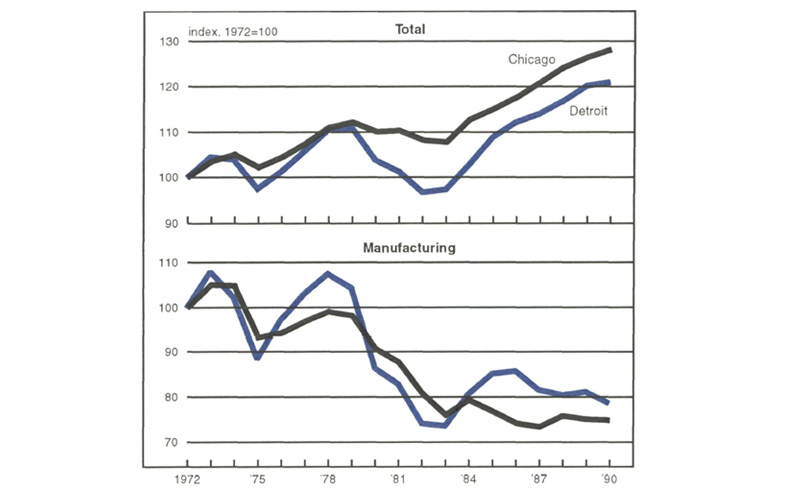

Over the past 15 to 20 years, Chicago has fared a little better than Detroit in the job growth derby, at least up through the pre-recession year of 1988 (see figure 2). From 1972 to 1988, Detroit gained 20.3% in total employment in comparison to Chicago’s 24.3 (the U.S. gained 43%). Over that same period, however, Chicago has lost over 24% of its manufacturing jobs in comparison to 19% in Detroit. (The U.S. gained 3%; the Detroit area’s losses would be somewhat muted if we were to include the rapidly growing Ann Arbor area in our definition of the metropolitan area.)

2. Employment

In light of this loss in its manufacturing base, Chicago’s total job growth and changeover to a service-based economy are all the more remarkable. Likewise, given the fact that Detroit’s auto industry has weathered two energy price shocks and a storm of foreign competition, the metropolitan area’s “internal transformation” of its primary industry and its loss of only 19% of its manufacturing jobs does not seem so bad.

Due in part to slumping auto sales, Detroit’s job growth has slipped further behind Chicago’s during the past three years of weak economic growth. However, it is uncertain whether the recent slippage will be sustained once the dust has settled on the recession and recovery period. To be sure, there are chronic structural problems in the Detroit and Michigan economies stemming from the reshuffling geography of auto assembly in the U.S. But the performance differences (with Chicago outperforming Detroit during the 1990-92 period) may now be dissipating. More recently, the Chicago area economy has had problems of its own. A series of economic changes and one-time events began to impact Chicago during late 1990 and the whole of 1991 that revealed its underlying weaknesses. Chicago’s construction bubble has now popped; both commercial and industrial vacancy rates have moved sharply higher. Meanwhile, overseas exports have slowed, and the Chicago area’s manufacturing specialties have cooled. At the same time, Detroit’s auto industry has begun to experience a turnaround in sales and production. Moreover, domestic auto companies are gaining back some share of sales, which had been lost to competitors during the recession. So far in 1992 Detroit’s manufacturing employment appears to be holding up better than the nation’s, even though total payroll employment continues to erode.

What does the future hold?

Chicago has diversified its industries, while Detroit has been slower to do so. Detroit’s concentration in durable goods employment has increased since 1969 while Chicago’s has fallen. If domestic car manufacturers continue to experience sluggish sales, we would expect Detroit’s fortunes to sag accordingly. Certainly, Michigan will continue to grapple with upheaval in its auto industry as GM continues its massive restructuring between now and 1996.

However, not all of the restructuring of domestic auto companies will involve massive downsizing. Right now, all three domestic automakers are changing their modes of management operation and manufacturing processes as well. Following GM’s joint venture experience with Toyota in Fremont, the company has been reorganizing and adopting new production techniques at Saturn and throughout its primary operations. Ford has increased quality and pared costs to meet worldwide standards. Chrysler has introduced its new “LH” fleet of mid-sized cars that has been developed using new supplier relationships, production methods, development processes, and management techniques. It now appears that the Big Three are poised to gain back some lost market share and to hold onto it as well.

Chicago’s growth and transformation will be bolstered by any manufacturing revival within its large sphere of midwestern influence, including Detroit’s. As midwestern goods producing industries such as factories and farming expand, purchases of services from the region’s service centers expand along with them.

If there is a lesson for regions about restructurings in these two metropolitan areas, it may be that each region must chart its own best course. Diversifying a region’s mix of industries away from its historic specialty may not always be winning strategy. Depending on a region’s industries and companies, and on the underlying global demand for products, promoting high performance in a specialized activity can be more rewarding for a region than the “portfolio management” approach of diversifying to achieve an industry mix more similar to the national mix. For some regions, services will drive the future economy; for others, manufacturing related activities will continue to be the mainstay.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output index (1987=100)

| October | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMI | 110.4 | 108.6 | 110.3 |

| IP | 109.9 | 109.5 | 109.0 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, saar)

| November | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autos | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.7 |

| Light trucks | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

Purchasing manager’s association: production index

| November | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 60.0 | 54.1 | 52.4 |

| U.S. | 60.1 | 54.3 | 53.2 |

Purchasing Managers’ Surveys (index)

Sources: The Midwest Manufacturing Index (MMI) is a composite index of 17 industries based on month hours worked and kilowatt hours. IP represents the FRBB industrial production index for the U.S. manufacturing sector. Autos and light trucks are measured in annualized physical units, using seasonal adjustments developed by the Federal Reserve Board. The PMA index for the U.S. is the production components of the NPMA survey and for the Midwest is a weighted average of the production components of the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee PMA survey, with assistance from Bishop Associates and Comerica.

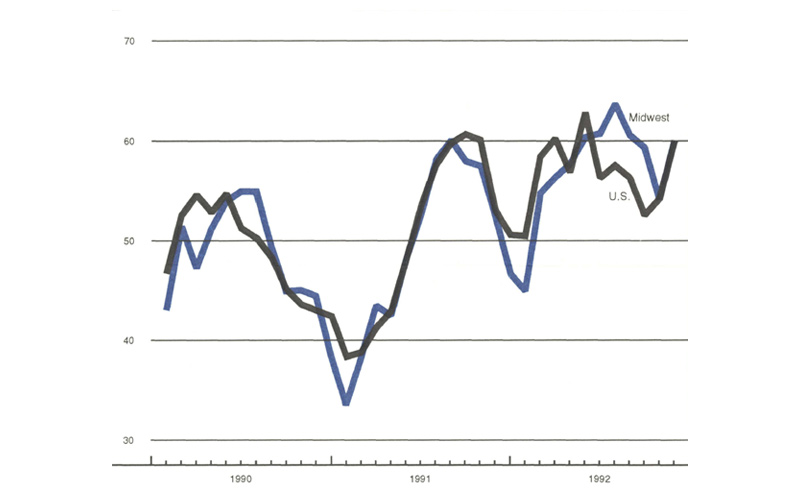

Midwest manufacturing activity began to show some solid improvement in the fourth quarter, with Purchasing Managers’ Surveys around the region (and the nation) regaining some momentum. Auto production gains helped, but further contributions will depend on improved sales. The question remains as to whether this time the recovery will be able to sustain these recent gains.

The composite index of Midwest Purchasing Managers’ Surveys in November rose to 63.0 and continued to lead the nation. Chicago posted the strongest gains, but solid gains were recorded in both Milwaukee and Detroit. Detroit’s gains, however, were based primarily in its auto related sector.

Notes

1 Throughout the discussion here, “Chicago” refers to the Chicago metropolitan area as defined by the eight counties of Cook, DuPage, Grundy, Kane, Kendall, Lake, McHenry, and Will. “Detroit” refers to the seven-county area including LaPeer Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, St. Clair, and Wayne.

2 For example, note the development efforts as described by the Commercial Club of Chicago’s “Jobs for Metropolitan Chicago” report in 1985 that largely excluded manufacturing in its vision of Chicago’s future. Recent forecasts from the Regional Economic Applications Lab (REAL) show a continued shrinkage of durable goods employment in the Chicago area.