Monetary Policy: Avoiding the Hazards

Introduction

Good afternoon. Thank you, Travis.

Before I begin, I should note that my commentary reflects my own views and does not necessarily represent those of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) or within the Federal Reserve System. I’m going to use the term “FOMC” a lot. The Federal Reserve Board Governors and 12 Reserve Bank Presidents comprise this committee, and it is the group that makes monetary policy decisions for the United States.

Although my comments today will be about the U.S. economy and current monetary policy challenges that the Federal Reserve faces, I’d like to start with an observation about how basic decision-making challenges, similar to what I’m sure many of you regularly face, inform my policy analysis. In 2002, a psychologist by the name of Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work related to the field of behavioral economics.1 He is the author of a recent book entitled Thinking, Fast and Slow.2 An overly simplistic synopsis of the book is this: Our minds are wired in complicated ways to solve a variety of problems. Sometimes our quick reaction brain reaches the right solution, and other times it doesn’t. That’s when our slower, more thoughtful brain is required to get it right. Recently, I read an interview with Kahneman with the following subtitle: “What would I eliminate if I had a magic wand? Overconfidence.”3 This certainly is food for thought.

Given my economics training, my 20 years of experience attending FOMC meetings and the outstanding analyses of my talented Fed staff, I often feel extremely confident about my monetary policy views. But policy mistakes can and have happened throughout the long history of central banks. With this in mind, I’m constantly asking myself, “What if my policy proposals end up being wrong?” So I try to have a Plan B ready to go. For example, in 2011, in an effort to provide more monetary accommodation, I proposed that the FOMC adopt explicit forward guidance that linked our future policy actions to outcomes for unemployment and inflation. This guidance included a safeguard that said accommodation would be dialed back if it unintentionally kindled unacceptably high inflation. So, the proposal had a Plan B imbedded in it. The Federal Open Market Committee adopted a policy along these lines in late 2012. As it turned out, we didn’t need to invoke the safeguard, but I still think it played a critical Plan B role in the policy’s effectiveness.

As my speech progresses, I hope you will see similar attempts to provide risk safeguards in my comments today. First, though, I would like to begin with a discussion of the goals of monetary policy.

Goals of Monetary Policy — Are We There Yet?

Congress has charged the Federal Reserve with fostering financial conditions that achieve stable prices and maximum sustainable employment. These two goals —together known as our “dual mandate” — guide the Fed’s monetary policy decisions. The Federal Open Market Committee has translated these broadly defined mandates into operational goals.

For the first goal, the inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy. So the FOMC has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation. Since January 2012, the Committee has set an explicit 2 percent inflation target, measured by the annual change in the Price Index for Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE).4

For the second goal, quantifying the maximum sustainable level of employment is a much more complex undertaking. Many nonmonetary factors affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market. These factors can vary overtime and are hard to measure. Consequently, the Committee does not set a fixed goal for employment, but instead considers a wide range of indicators to gauge maximum employment.

Nonetheless, FOMC participants do provide their individual views of the longer-run normal level of unemployment that are consistent with the employment mandate. These can be found in the Committee’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), which are released four times a year and give participants’ forecasts of key economic metrics over the next three years and for the longer run.5 In the most recent SEP, which was released a little over three weeks ago, the median participant estimated that the normal long-run unemployment rate was 4.9 percent.6 My own assessment is in line with this projection.

Given these operational objectives, how close are we to achieving the dual mandate? There is no doubt that labor markets have improved significantly over the past seven years. Job growth has been quite solid for some time now. Last month’s number was somewhat weaker than expected but doesn’t change the overall view. And the unemployment rate has declined significantly from its peak of 10 percent in 2009 and currently stands at 5.1 percent. This is just two-tenths of a percentage point above the median long-run projection. However, a number of other labor market indicators lead me to believe that there still remains some additional resource slack beyond what the unemployment rate alone indicates: Notably, a large number of people who are employed part time would prefer a full-time job; the labor force participation rate is quite low, even after accounting for demographic and other long-running trends; and wage growth has been quite subdued.7

My colleagues on the FOMC and I project that over the next three years, the unemployment rate will edge down further and run slightly below its long-run sustainable level.8 I also believe the elements of “extra” labor-market slack I just mentioned will dissipate over that time. What is driving this forecast? Well, gross domestic product (GDP) growth appears to be well positioned to continue at a fairly solid, though not spectacular, pace for some time. In particular, consumer spending looks to be advancing at a healthy rate — supported in part by lower energy prices and, more importantly, by the improvements in the job market. We economists sometimes refer to this as “virtuous cyclical dynamics” — more jobs lead to more spending, which in turn leads to more jobs. So, although there are some risks, I am relatively confident that we will reach our employment goal within a reasonable period.

However, I am far less confident about reaching our inflation goal within a reasonable time frame. Inflation has been too low for too long. Core PCE inflation — which strips out the volatile energy and food components and is a good indicator of underlying inflation trends — has averaged just 1.4 percent over the past seven years. Core PCE inflation over the past 12 months was just 1.3 percent. The total PCE price index has barely budged, rising just 0.3 percent over the past year.

Most FOMC participants expect inflation to rise steadily from these low levels, coming in just a shade under the Committee’s 2 percent target by the end of 2017.9 My own forecast is less sanguine. I expect core PCE inflation to undershoot 2 percent by a greater margin over the next two years than do my colleagues. I expect core PCE inflation will be just below 2 percent at the end of 2018.

A number of factors inform my inflation forecast. First, low energy prices and increases in the dollar continue to generate downward pressure on consumer prices. Second, putting aside the swings in energy prices and the like, core inflation tends to change quite slowly — particularly when it is at low levels. So low core inflation today tends to be a harbinger of low overall inflation for some time. Third, wage growth has been very subdued, coming in around 2 percent to 2-1/2 percent for the past six years. This is well below the 3 to 3-1/2 percent pace we would expect in an economy growing at its potential with inflation at 2 percent. Although higher wage growth is not necessarily a strong predictor of inflation, it is a good corroborating indicator of underlying inflation trends.

So given these forces holding back inflation, why do I expect it to rise? Well, the influences from low energy and import prices are expected to be temporary. Additional improvement in the labor market should also help boost inflation. Another important determinant of actual inflation is the public’s perception of inflationary trends because these views get built into the pricing decisions of businesses and the wage aspirations of workers. Currently, these expectations appear to be higher than actual inflation. So they should also help boost inflation. Furthermore, economic theory tells us that in the long run, inflation is a monetary phenomenon, and my forecast for a gradual rise in inflation critically depends on monetary policy maintaining a highly accommodative stance for some time.

A Risk-Management Approach to Monetary Policy

As a policymaker, I try to rely on my expertise and judgment and that of my staff to chart a course for the future. But I am aware that I must also guard against overconfidence and have a good Plan B in hand in case obstacles materialize. In determining the best course for monetary policy, I believe the Fed should follow this principle. How does that apply to today’s situation?

Currently, there are some downside risks to reaching our maximum employment goal — namely, the potential for weak foreign activity to weigh on U.S. growth. But, as I noted earlier, we have made tremendous progress toward this goal. Economic growth appears to have enough momentum that I am fairly confident that we will reach our maximum employment goal within a reasonable time. However, to reiterate, I am far less confident that we can reach our 2 percent inflation target over the medium term because of a number of important downside risks to the inflation outlook. Now I recognize that “medium term” is somewhat vague. To a central banker it can mean 2 to 3 years or 3 to 4 years. It is more a term of art than science.

So what are these inflation risks? With prospects of slower growth in China and other emerging market economies, low energy and import prices could exert downward pressure on inflation longer than I anticipate. In addition, while many survey-based measures of long-term inflation expectations have been relatively stable in recent years, we shouldn’t take them as confirmation that our 2 percent target is assured. In fact, some survey measures of inflation expectations have ticked down in the past year and a half. Furthermore, financial market-based measures of inflation compensation have moved quite low in recent months. These could reflect either lower expectations of inflation or a heightened concern for the economic conditions that are associated with low inflation. Adding to my unease is anecdotal evidence: I talk to a wide range of business contacts, and none of them are mentioning rising inflationary or cost pressures. None of them are planning for higher inflation. They don’t expect it.

How does this asymmetric assessment of risks to achieving the dual mandate goals influence my view of the most appropriate path for monetary policy over the next three years? It leads me to conclude that a later liftoff and a gradual normalization of our monetary policy framework will best position the economy for the potential challenges ahead.

Before raising rates, I would like to have more confidence than I do today that inflation is indeed beginning to head higher. Given the current low level of core inflation, some evidence of true upward momentum in actual inflation is critical to this assessment. I believe that it could well be the middle of next year before the headwinds from lower energy prices and the stronger dollar dissipate enough so that we begin to see some sustained upward movement in core inflation. After liftoff, I think it would be appropriate to raise the target interest rate very gradually. This would give us sufficient time to assess how the economy is adjusting to higher rates and the progress we are making toward our policy goals.

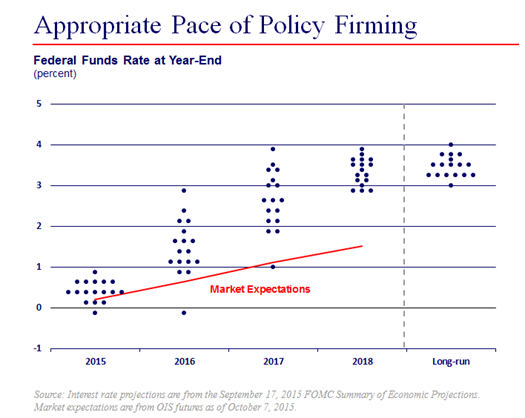

Overall, my view of appropriate policy is somewhat more accommodative than the views held by the majority of my colleagues. In addition to economic and inflation forecasts, FOMC participants also submit individual assessments of the appropriate monetary policy that support their SEP forecasts. These policy judgments are summarized in the FOMC’s well-known “dot plot.”

This is the chart I handed you that shows FOMC participants’ views of the appropriate target federal funds rate by the end of each year for 2015 to 2018 and also over the longer run. Each participant’s fed funds rate forecast is shown as a distinct dot at each of these time horizons. Focusing on the median policy projection for the end of 2015, most of my colleagues think that it will be appropriate to raise the target federal funds rate sometime this year. Over the next 3 years these prognostications envision a slow increase, to about 3-1/2 percent by the end of 2018.10 On average, this path is consistent with the target federal funds rate increasing by 25 basis points at every other FOMC meeting over the next three years. This is certainly a gradual path by historical standards. It is even slower than the so-called “measured pace” of increases over the 2004–06 tightening cycle, which was 25 basis points per meeting.

As I said, I think policy should be somewhat more accommodative than this course of action suggested by the median forecasts of the latest SEP. In my view, an extra-patient approach is warranted for several reasons. And you will see that my logic reflects my risk-management approach to monetary policy.

First, after several years of below-target inflation performance and in light of the downside risks to the inflation outlook, appropriate policy should provide enough accommodation to generate a reasonable likelihood that inflation in the future would moderately exceed 2 percent. Aggressive pursuit of achieving our 2 percent target sooner rather than later does indeed open the possibility of modestly overshooting 2 percent. But this is not as heretical as it might first appear. After all, this is a consequence of having a symmetric inflation target: It is difficult to average 2 percent inflation over the medium term if the track record and near-term projections of inflation are all less than 2 percent.

Furthermore, maintaining credibility is key to effective policy. Historically, central bankers have established their credibility by defending their inflation target from undesirably high inflation. Today, policy needs to validate our claim that we aim to achieve our 2 percent inflation target in a symmetric fashion. Failure to defend our inflation goal from below may weaken the credibility of this claim. The public could begin to mistakenly believe that 2 percent inflation is a ceiling — and not a symmetric target. As a result, expectations for average inflation could fall, lessening the upward pull on actual inflation and making it even more difficult for us to achieve our 2 percent target.

Second, consider the other policy mistakes we could make. One possibility is that we begin to raise rates only to learn that we have misjudged the strength of the economy or the upward tilt in inflation. In order to put the economy back on track, we would have to cut interest rates back to zero and possibly even resort to unconventional policy tools, such as more quantitative easing.11 I think quantitative easing has been effective, but it clearly is a second-best alternative to traditional policy. This scenario is not merely hypothetical. Just consider the recent challenges experienced in Europe and Japan. Policymakers tried to raise rates from their lower bounds; but faced with faltering demand, they were forced to reverse course and deploy nontraditional tools more aggressively than before. And we all know the subsequent difficulties Europe and Japan have had in rekindling growth and inflation. So I see substantial costs to premature policy normalization.

An alternative potential policy mistake is that sometime during the gradual policy normalization process, inflation begins to rise too quickly. Well, we have the experience and the appropriate tools to deal with such an outcome. Given how slowly underlying inflation would likely move up from the current low levels, we probably could keep inflation in check with only moderate increases in interest rates relative to current forecasts. And given how gradual the projected rate increases are in the latest SEP, the concerns being voiced about the risks of rapid increases in policy rates if inflation were to pick up seem overblown to me. For example, we could raise the funds rate 100 basis points more than envisioned by the median SEP projection in a year simply by increasing rates 25 basis points at every meeting instead of at every other meeting — that’s hardly a steep path of rate increases.

Furthermore, as I just outlined, there is no problem in moderately overshooting 2 percent. After several years of inflation being too low, a modest overshoot simply would be a natural manifestation of the Federal Reserve’s symmetric inflation target. Moreover, such an outcome is not likely to raise the public’s long-term inflation expectations either — just look at how little these expectations appear to have moved with persistently low inflation readings over the past several years. So, I see the costs of dealing with the emergence of unexpected inflation pressures as being manageable.

All told, I think the best policy is to take a very gradual approach to normalization. This would balance both the various risks to my projections for the economy’s most likely path and the costs that would be involved in mitigating those risks.

Now I would like to emphasize that while I favor a somewhat later lift off than many of my colleagues, the precise timing for first increase in the federal funds rate is less important to me than the path the funds rate will follow over the entire policy normalization process. After all, today’s medium and longer-term interest rates depend on market expectations of the entire path for future rates, not just the first move. In turn, these medium and longer-term rates are key to the borrowing and spending decisions of households and businesses.

Accordingly, when thinking about the initial stages of normalization, I find it useful to focus on where I think the federal funds rate ought to be at the end of next year given my economic outlook and assessment of the risks. And right now, regardless of the exact date for lift-off, I think it could well be appropriate for the funds rate to still be under one percent at the end of 2016.

There is an important caveat, though, to my comment downplaying the importance of the exact date of lift-off. It is critically important to me that when we first raise rates the FOMC also strongly and effectively communicates its plan for a gradual path for future rate increases. If we do not, then markets might construe an early liftoff as a signal that the Committee is less inclined to provide the degree of accommodation than I think is appropriate for the timely achievement of our dual mandate objectives. I would view this as an important policy error.

Effective Communications Is a Critical Policy Tool

I cannot stress enough how critical it is for monetary policymakers to effectively communicate how they aim to achieve their long-run goals and strategies. They must clearly describe how their views on the appropriate path for monetary policy will help generate outcomes for employment and inflation that are consistent with achieving the mandated goals within a reasonable time frame. Moreover, they must demonstrate they have appropriately considered the risks to their outlooks on the economy. I hope I have done that for you today by laying out my forecast for the economy and what I consider to be the appropriate path for policy.

We also need to be clear about how monetary policymakers will react to new data as the economy evolves. We talk a lot about data dependence, but what does that really mean? To me, it involves the following: 1) evaluating how the new information alters the outlook and the assessment of risks around that outlook; and 2) adjusting my expected path for policy in a way that keeps us on course to achieve our dual mandate objectives in a timely manner. So, if in the coming months inflation rises more quickly than I currently anticipate and appears to be headed to undesirably high levels, then I would argue to tighten financial conditions sooner and more aggressively than I presently do. If instead inflation headwinds persist, I would advocate a more gradual approach to normalization than I currently envision. In either case, my policy forecasts would change and I would explain how and why they did.

Such communication helps clarify our reaction to new information — the so-called Fed reaction function you hear financial market analysts talk about. This in turn makes it easier for households and businesses to plan for the future. Such transparency is a key feature of goal-oriented, accountable monetary policy — the kind of policy that the Federal Reserve is committed to providing today, and the kind of policy that the Federal Reserve is committed to providing in the future.

Notes

1 In its announcement, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (2002b) cites Kahneman “for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty.” For further details on his research, see Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (2002a).

2 Kahneman (2011).

3 Shariatmadari (2015).

4 This was first acknowledged in Federal Open Market Committee (2012). It remains in the most recent statement of our longer-run goals; see Federal Open Market Committee (2015b).

5 Specifically, the participants provide their forecasts of real GDP growth, the unemployment rate and inflation, along with individual assessments of the appropriate monetary policy that support those forecasts.

6 See Federal Open Market Committee (2015a) for the most recent projections.

7 See Evans (2014a, 2014b, 2014c, 2015a, 2015b and 2015c).

8 According to the median forecast of latest SEP, the unemployment rate is projected to edge down further next year to 4.8 percent and to remain at that level through the end of 2018.The median forecast for real gross domestic product (GDP) growth is 2.1 percent for 2015. It rises to 2.3 percent in 2016 before gradually edging down to 2 percent (the longer-run estimate of real GDP growth) in 2018 (Federal Open Market Committee, 2015a).

9 In the latest SEP, the median forecast for both core and total PCE inflation is 1.7 percent in 2016, 1.9 percent in 2017, and 2 percent in 2018 (Federal Open Market Committee, 2015a).

10 Specifically, the median projected path for the target federal funds rate is 0.4 percent at the end of 2015; 1.4 percent at the end of 2016; 2.6 percent at the end of 2017; and 3.4 percent at the end of 2018. The median projection for the longer-run level of the federal funds rate is 3.5 percent (Federal Open Market Committee, 2015a).

11 For more about the quantitative easing programs (also referred to as large-scale asset purchases) and the rationale behind them, see Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2015).

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2015, “What are the Federal Reserve's large-scale asset purchases?,” Current FAQs, January 16.

Evans, Charles L., 2015a, “Exercising caution in normalizing monetary policy,” speech, Swedbank Global Outlook Summit, Stockolm, May 18.

Evans, Charles L., 2015b, “Risk management in an uncertain world,” speech, London, March 25.

Evans, Charles L., 2015c, “Low inflation calls for patience in normalizing monetary policy,” speech, Lake Forest-Lake Bluff Rotary Club, Lake Forest, IL, March 4.

Evans, Charles L., 2014a, “Monetary policy normalization: If not now, when?,” speech, BMO Harris and Lakeland College Economic Briefing, Plymouth, WI, October 8.

Evans, Charles L., 2014b, “Is it time to return to business-as-usual monetary policy? A case for patience,” speech, 56th National Association for Business Economics (NABE), Chicago, September 29.

Evans, Charles L., 2014c, “Patience is a virtue when normalizing monetary policy,” speech, Peterson Institute for International Economics conference, Labor Market Slack: Assessing and Addressing in Real Time, Washington, DC, September 24.

Federal Open Market Committee, 2015a, Summary of Economic Projections, Washington DC September 17.

Federal Open Market Committee, 2015b, “Statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy,” Washington, DC, as amended effective January 27.

Federal Open Market Committee, 2012, press release, Washington, DC, January 25.

Kahneman, Daniel, 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 2002a, “Foundations of behavioral and experimental economics: Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith,” Stockholm, December 17.

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 2002b, press release, Stockholm, October 9.

Shariatmadari, David, 2015, “Daniel Kahneman: ‘What would I eliminate if I had a magic wand? Overconfidence,’” Guardian, July 18.