Smoke from wildfires has increased dramatically in the United States in recent years. As a result, new populations, including many living in urban areas in the eastern parts of the country, have become increasingly exposed to particulate matter from wildfire smoke. These trends reflect the fact that larger and more intense plumes travel farther, affecting regions that have traditionally been far less exposed to wildfire smoke. In short, wildfire smoke has now become a national problem.

There is a growing literature demonstrating the consequences to both health and economic activity from particulate matter, including from wildfire smoke.1 This includes increasing mortality among the elderly,2 as well as lowering labor income through labor market disruptions that likely extend beyond the days of smoke exposure.3 The channels connecting air pollution and economic activity are diverse and include changes in labor demand, productivity, and cognitive performance.4

In this Chicago Fed Letter, we use satellite data that record the extent of smoke plumes and combine this with population data to document the changing patterns in exposure to wildfire smoke. First, we highlight that there has been a rapid and unprecedented increase in overall exposure since 2020. In 2023, the average American resident experienced nearly 150 days of complete wildfire smoke coverage in their county, a more than sevenfold increase over the levels experienced from 2006 to 2020. We further show that this increase is not driven by a small number of highly exposed counties—instead, the increase is pervasive across most counties in the country.

Second, we show how this pattern has changed across different U.S. regions. A key finding is that smoke exposure has risen the most in regions outside of the West, even though many wildfires occur in the western United States or Canada. This highlights that the externalities, or social costs, of wildfire smoke, are increasingly experienced by populations far removed from the origins of these wildfires, suggesting the growing need for national and international policies to offset the impacts of wildfire smoke on populations distant from the fires themselves.

Third, we document how this geographical shift in the direction of smoke plumes alters the relative exposure of different demographic groups. In recent years, Black residents have become relatively more exposed to wildfire smoke than White residents, while Hispanic residents have become relatively less exposed. As environmental justice concerns have grown as a policy consideration in the United States, this emerging pattern of unequal exposure by race and ethnicity may be important for policymakers to understand. We do not find greater inequality in recent years, however, when we look at exposure to wildfire smoke by income levels or the poverty rate.

Data and methods

For wildfire smoke data, we use digital maps based on satellite data showing the plumes of daily smoke coverage from 2006 to 2023, constructed by imaging experts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Hazard Mapping System. We overlay these digital maps with U.S. county boundaries. We define a county as having a “smoke day” if the county is completely covered by a smoke plume that day.5 This allows us to calculate the number of smoke days for each county in each year. Since we are not accounting for days in which the smoke coverage does not completely cover a county, this measure is a lower bound for smoke exposure. Our measure also does not take into account the intensity of the smoke plume, which is only available for more recent years. For county population data, we use the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual population estimates by county.

We combine the data on smoke days and population to create a measure of smoke days per person for each year from 2006 to 2023 by averaging across counties.6 This measure reflects the average number of days a given person in the United States experienced complete smoke coverage in their county in a year. It is worth noting that smoke plume coverage is an atmospheric measurement that might not be perceptible to all individuals on the ground. However, we have validated our measure of smoke days and find that it is strongly associated with particulate matter readings.7

Results

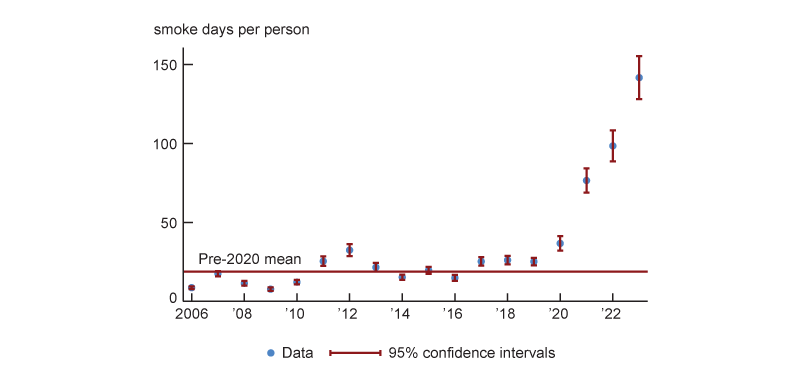

In figure 1, we plot the average smoke days per person by year for 2006–23. The red horizontal line marks the pre-2020 average smoke days per person, which was approximately 20 smoke days per person. Starting in 2020, however, there is a clear upward trend. In 2022 there were 100 smoke days per person, and in 2023 this rose even further to nearly 150 smoke days per person, more than seven times the pre-2020 average. This vast increase in smoke exposure is highly statistically significant, as demonstrated by the 95% confidence intervals associated with each annual estimate.8

1. Average smoke exposure per person, 2006–23

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System and U.S. Census Bureau County Population Estimates, 2006–23.

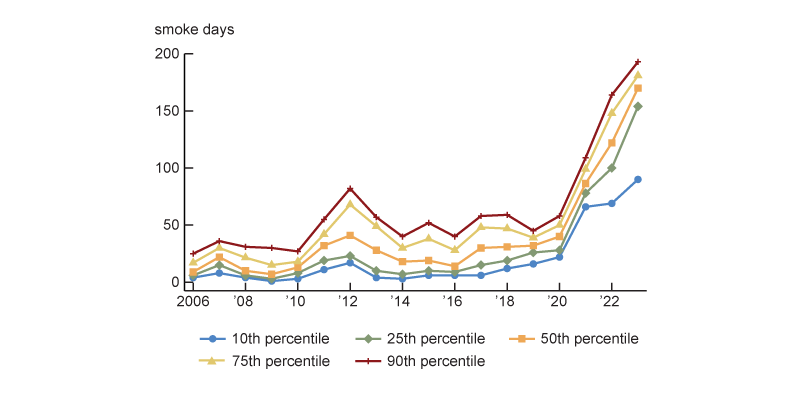

We next consider whether this dramatic increase in smoke exposure since 2020 is due to an increase in intensity in places that were already often exposed or whether it results from a more widespread increase affecting many counties. To shed light on this, in figure 2, we plot several percentiles of the county-level distribution of smoke days by year. Specifically, we show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of the county smoke-day distribution. In each year after 2020, all of these percentiles increase markedly, indicating that these changes in smoke exposure are broad-based and affect many counties, rather than being driven by a small number of outlier counties. Indeed, in 2023 the median county is exposed to approximately 170 complete smoke coverage days. Remarkably, in 2023 the 10th percentile county had higher smoke exposure than the 90th percentile county in 2020.

2. Distribution of county smoke coverage days, 2006–23

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System.

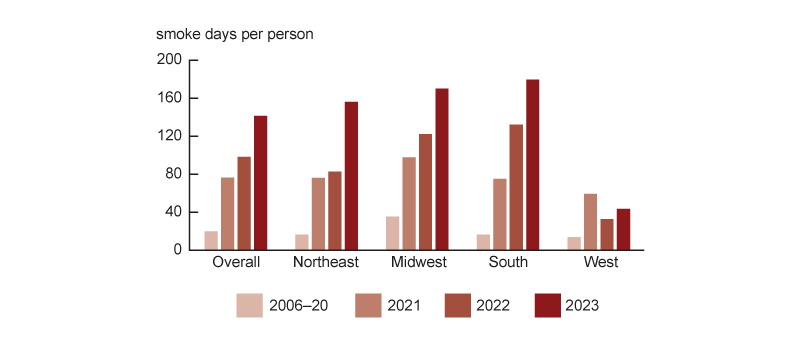

While much wildfire activity occurs in the American West, smoke plumes can travel thousands of miles and affect geographically disparate areas. In panel A of figure 3, we examine average smoke days per person by region, showing the 2006–20 average and then the yearly averages for 2021, 2022, and 2023. While all regions experienced increases in 2021–23 relative to previous years, the increase was notably muted for the western region—the other regions record 150–180 smoke days per person in 2023, whereas the West sees only 44 smoke days per person.

3. Smoke exposure trends by region

A. Regional differences

B. High-fire versus low-fire states

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System and U.S. Census Bureau County Population Estimates, 2006–23. Fire data is from the National Interagency Coordination Center.

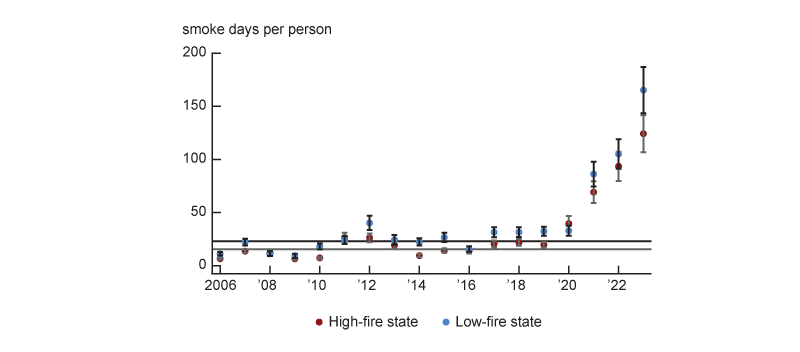

We further highlight how this emerging regional heterogeneity has led to a difference in smoke exposure between states that historically have been “low-fire” states and states that have been “high-fire” states in panel B of figure 3.9 In 2023, there was a significantly higher level of exposure in low-fire states.

These findings also highlight the increasing divergence between the places that are experiencing the harms from smoke, and therefore bearing the costs of the smoke, and the places where the fires start, and where fire control and suppression policies are often set. A wide range of local policies, such as building codes that allow construction near fire-prone areas, fuel clearing, and controlled burning, contribute to the severity of wildfires, which have implications for states far downwind. Local policymakers might not take into account the benefits that will accrue to downwind communities and may have less incentive to enact some of the costlier policies. This suggests a need for a coordinated national, or international, response that can be attentive to costs and benefits no matter where they occur.

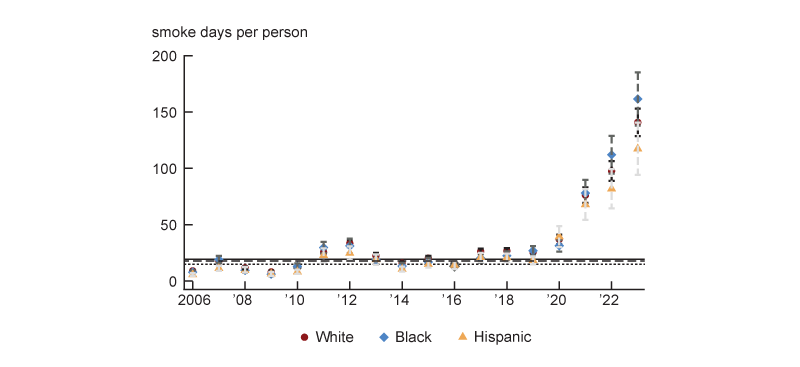

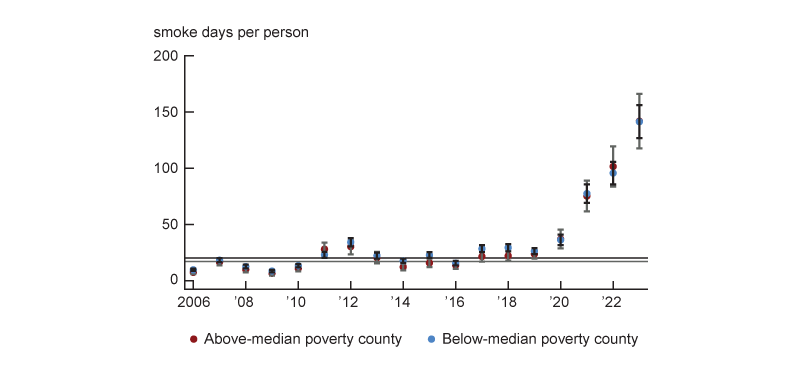

Finally, we explore issues related to environmental justice in figure 4, where we show how different demographic groups have been affected by the surge in wildfire smoke in recent years. In panel A, we show that in 2023, Black residents experienced 162 days of smoke exposure compared with 141 days for White residents and 117 days for Hispanic residents.10 The gap between Black and White residents of about 20 days of smoke exposure is similar in magnitude to the overall average annual smoke exposure experienced by the average resident from 2006 to 2019. In panel B, however, we show that there is no difference in exposure by the poverty rate in a county.

4. Differences by race/ethnicity and economic status

A. Racial and ethnic differences

B. Economic differences

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System and U.S. Census Bureau County Population Estimates, 2006–23. Poverty rates are from the 2010 U.S. Census.

Summary

We document trends in U.S. wildfire smoke exposure over the period covering 2006–23. We show that there was a dramatic increase in exposure starting in 2020, with the average U.S. resident experiencing nearly 150 days of complete smoke coverage in their county in 2023, as opposed to a mean of approximately 20 smoke days before 2020. This growth in exposure is not driven by an increase in a few highly exposed counties—instead, the whole distribution of county-level smoke exposure has shifted upward, often affecting previously unexposed areas. Additionally, we document that this trend is driven by increases in exposure, especially in the South, Midwest, and Northeast regions. While the West has experienced an increase in smoke exposure, it is small relative to those observed in other regions. Previous research has established that this increase in exposure is likely to have meaningful negative implications for the health and economic activity of the entire United States. The emerging divergence between the places where the fires start and the places where the costs of the smoke are borne is an important issue for policymakers to grapple with.

Notes

1 Recent research has shown that wildfire smoke already accounted for about one-third of all particulate matter pollution in 2022 (Burke et al., 2023).

2 See Deryugina et al. (2019) and Connolly et al. (2024).

3 See Borgschulte, Molitor, and Zou (2023).

4 See Fu, Viard, and Zhang (2021), Graff Zivin and Neidell (2018), and Künn, Palacios, and Pestel (2023).

5 We follow the methodology in Borgschulte, Molitor, and Zou (2023).

6 Specifically we use the following formula, where t denotes year and c denotes county: ${{(Smoke\,Days\,per\,Person)}_{t}}=\frac{1}{c}\sum\nolimits_{t=t,\,c\in C}{{}}\frac{Smoke\,Day{{s}_{ct}}\times County\,Populatio{{n}_{ct}}}{Mean\,County\,Populatio{{n}_{t}}}$.

7 We find that one additional smoke day in a county is associated with about five additional micrograms per cubic meter of wildfire smoke particulate matter (pm 2.5).

8 The confidence intervals in our results come from ordinary least square regression models of smoke days per person on year indicators estimated using our county-by-year data.

9 We define low-fire states as states with below-median wildfire acreage burned according to the National Interagency Fire Center and high-fire states as those states above-median on this measure.

10 We calculated race-specific rates by repeating the calculations of wildfire smoke coverage days using only individuals in a specific race to weight county smoke exposure by population.